I picked these tests at random, essentially the top tests in a stack. They are entirely representative of the group. These are samples of the “bubble tests,” as the kids and I call them. Written by an outside consulting firm, these tests are being used for … more benchmarking? More data? Spreadsheet practice? On the plus side, the bubble tests don’t count in their grade. I tell them to take the bubble tests seriously; The results are being recorded in spreadsheets that may be used for later class placement or something. It’s best to take all tests seriously whether you know why you are administering them or not.

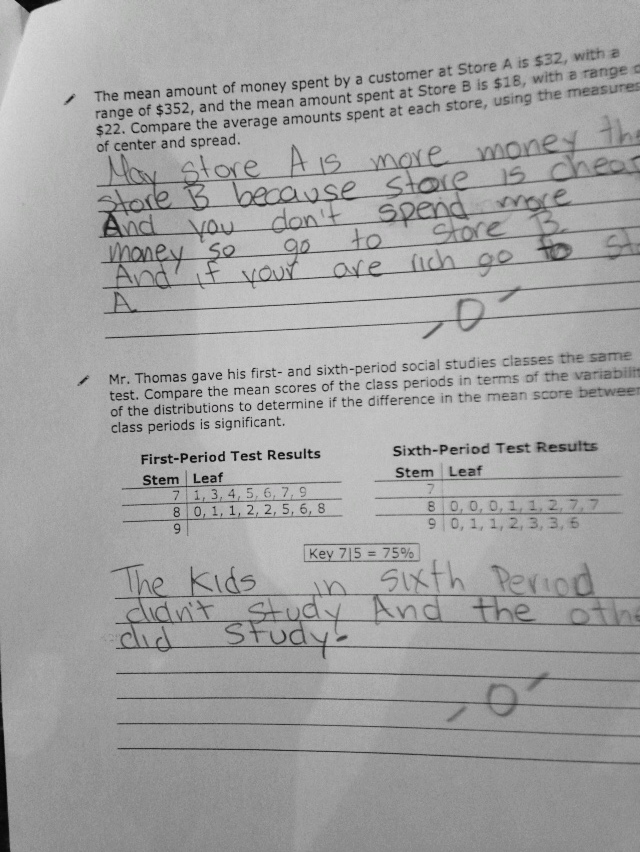

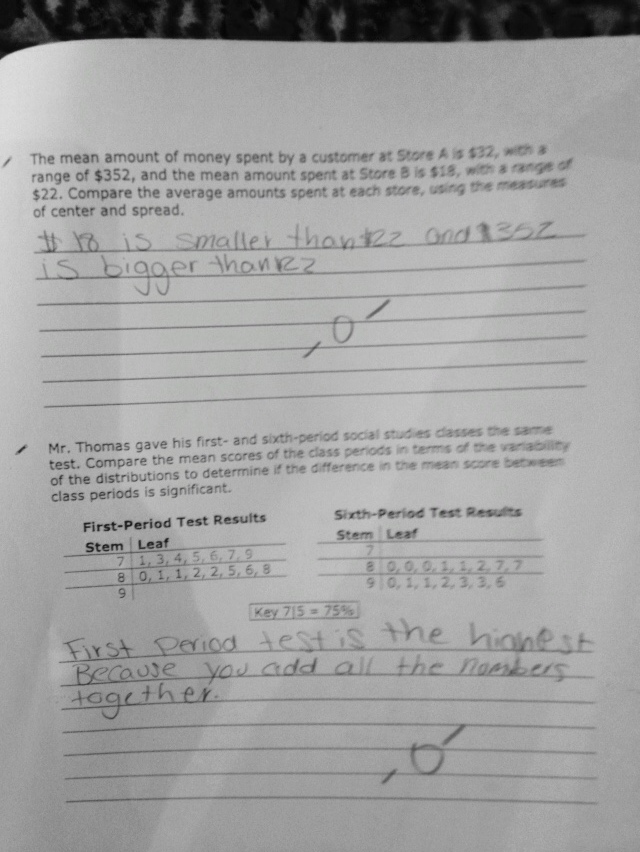

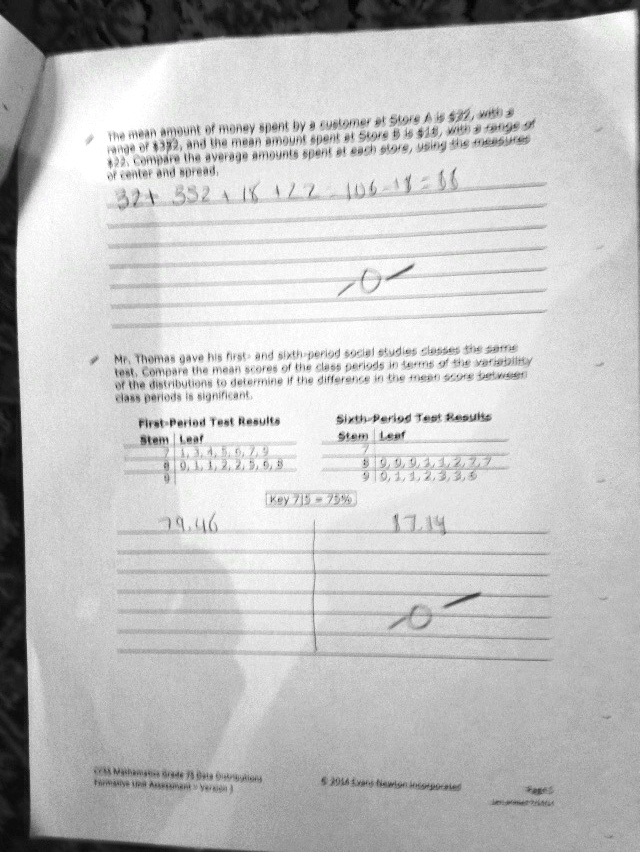

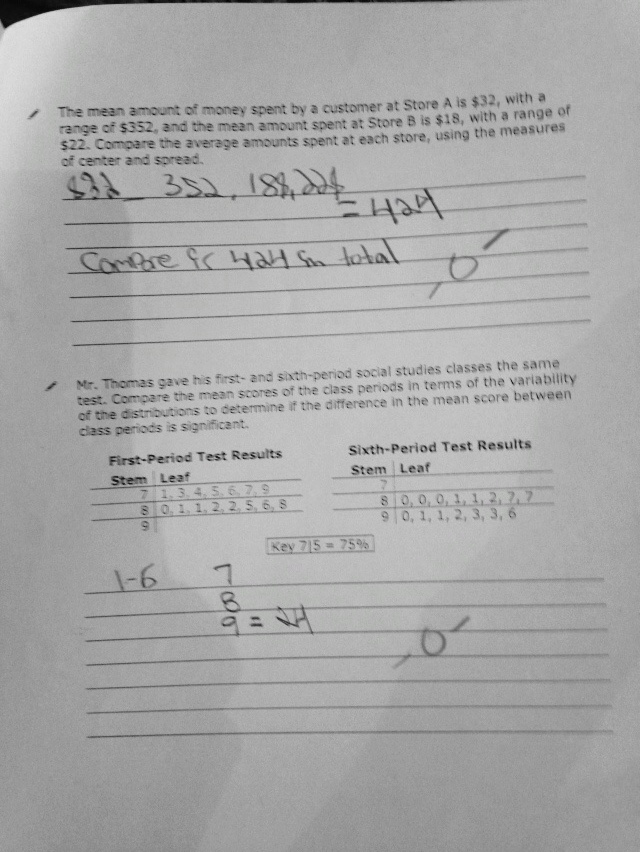

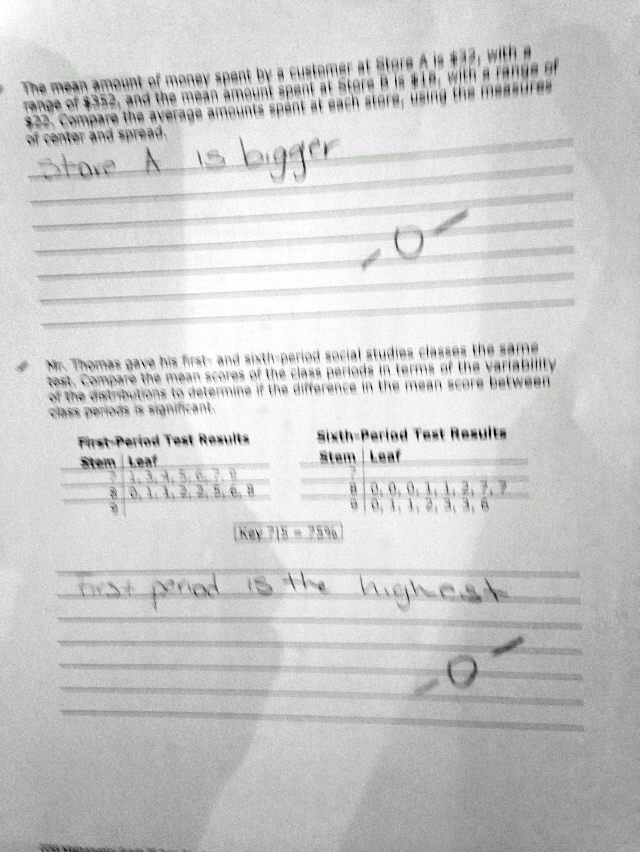

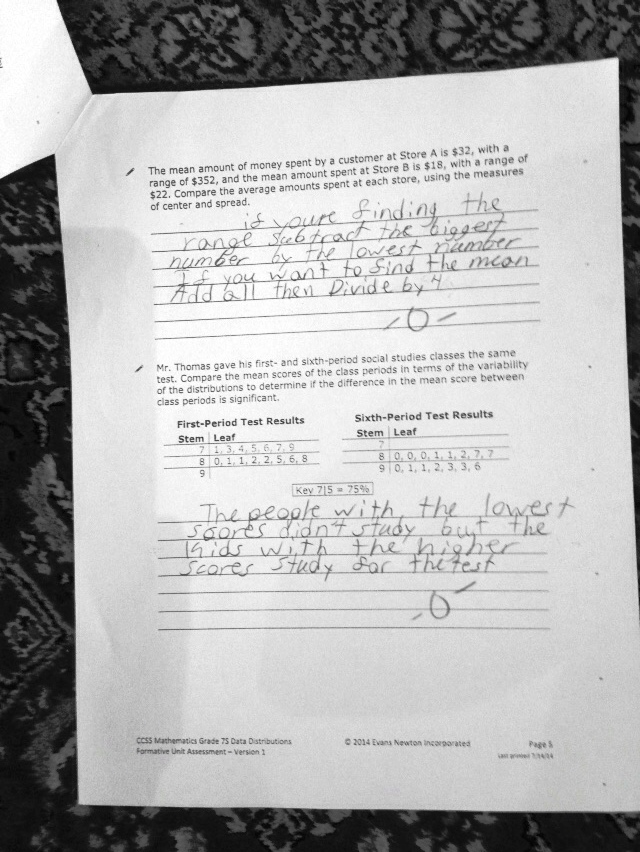

Coaches bring me bubble sheets already labeled with individual student names. I pass the sheets out to the appropriate students. I give them copies of the inappropriate tests that go with these copies. How do I know the tests are inappropriate? Well, for one thing, my students never pass these tests. I ought to check to see if someone snuck through on one. Some pictures will help show what I mean. I apologize for the poor quality of the pictures. The whim to take photos came at the last minute before I was supposed to turn these tests over to academic coaches. I wish I’d taken more pictures, but these are representative of the whole. I will take more pictures of the next batch.

There’s a spreadsheet somewhere. O.K. I’ll try to find the spreadsheet.

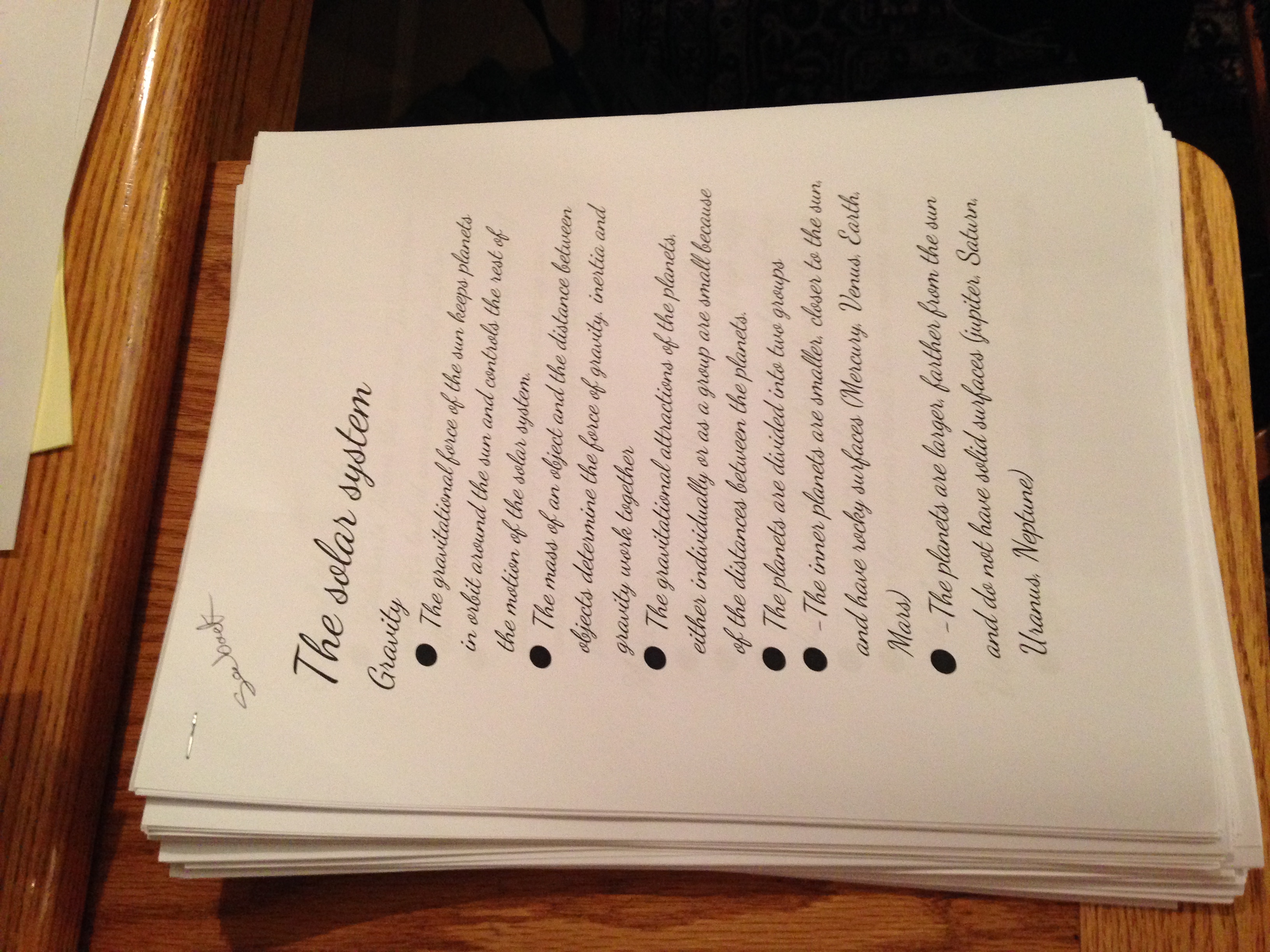

I will observe that some of these kids could do a better job today. They’ve made progress. My classes pretty much all understand stem-and-leaf plots now. Their MAP (Measures of Academic Progress, a benchmark test) show significant growth overall. Admin appears happy enough with my scores and admin is frantic to get school scores up. They would have done better if we could have spent more time on measures of central tendency. But outsiders have created the curriculum and pacing for the year. We were not allowed that time. Given that these kids entered my class scoring from a 1st to 5th grade level in math, according to MAP scores, with most of the group in the middle of that range, these questions were wholly inappropriate, especially for a group of bilingual students with English challenges. They were also inappropriate for the grade’s special education students who had to take exactly the same test. To be clear, I did not cherry-pick this group of tests. I just grabbed a few from the top of the stack.

I wasted my time and their time administering this test. We have a great deal of remedial math to cover, as the tests make evident. The bubble tests may be reasonable instruments for many students in regular classes, but they are not helping the students who wrote the answers above.

On the plus side, grading these tests is absurdly easy. Also on the plus side, the students will never see these tests after they complete them. I grade the problems they write out and hand the answer sheets to coaches who grade the multiple choice section. Then the tests vanish except for red ink in a spreadsheet that I haven’t bothered to look at for months.

In the real world, a test should be based on material that has been taught — and not blasted through at light-speed because the whole grade has to march in lock-step to some pie-in-the-sky curriculum — with ample study opportunities provided beforehand. Then that test should be reviewed shortly afterwards so that students can see where the test went right and where it went wrong. Tests can be excellent learning tools when used correctly.

I’d say a bonfire is the only practical use for the tests above.