(This will be another practical post mostly for newbies.)

I am a bit late writing this. Districts keep pushing school years back into the summer to allow more time to prepare for that annual state test on which careers may rise and fall. Some schools now start in July. But I hope this proves helpful to a group of readers.

Are you furiously putting up student work in your classroom to get ready for incoming parents? Are you helping students organize their work to show to their parents? At open house and parent-teacher conferences, parents will form their first impression of you. Taking time to create a caring, professional environment can go a long way toward making your year easier.

As parents enter, I recommend getting contact information first so this piece does not get forgotten. If parents say they don’t have a phone or an email address — in financially-disadvantaged districts, especially those with many immigrant parents, this is not uncommon — then try to get a contact phone or email. Somebody’s uncle will do. A few uncles and aunts are better. I suggest buying index cards. On the front of each index card, record a student’s name. Write down any contact information below that name.

I once coined a phrase I still like: Disconnected kids have disconnected phones. Disconnected kids need you to be able to reach parents somehow. The fact that poor behavior or lack of effort can get back to parents definitely improves behavior and effort, at least on the part of some students.

You will want to have folders of student work ready to view. If your class is keeping work in binders, this step should be simple. If you can find time before conferences, I would suggest trying to put sticky notes on binder items you want to share so you can find examples of good or problematic work quickly.

If you have not yet begun making students collect their work and keep that work in binders, I’d suggest starting this week. With luck, your school provides binders. If not, you can tell students to bring in binders, but that may prove frustrating as the excuses pile up and the days go by. I suggest going out and buying cheap binders. Let students purchase them at cost or below cost. I usually quietly give a few away.

Tell students that parents will see their binders. Help students by allowing time to put classwork and homework in binders. Regular reminders that these binders are for parents helps to get best student efforts.

Walk around to assist with organization as students file away their work. Teaching students to think about how to organize their papers does them a great service. By middle school, organizational deficits can sink less methodical kids as they try to keep track of six classes and six teachers. Sixth and seventh grade teachers — the best gift you can give your students will be the ability to create a system that will allow them to keep track of their work and their future responsibilities.

Oops! How did this post become, “Our Friend the Binder”?

Back to conferences. You have your organized, alphabetized binders. You have your parents and their contact information. You have any other forms the school wants them to sign while they are there, such as school handbooks, for example. Now what?

Some teachers prepare a PowerPoint on classroom plans and expectations, especially for open house events. Open house is not intended to be a time for one-on-one teacher conferences. Parents will try to engage you in these conferences anyway. If that happens, say something short to indicate you are available to talk about Mary, but you can’t have that conversation during open house. I’d suggest being prepared with a list of times for possible parent meetings later.

For parent-teacher conferences, you will want access to student work, grades and other data, such as test scores and attendance. The data’s not the conversation, however. It’s too easy to get lost in a data dump nowadays because we have so much data. If you find yourself doing all the talking, as you explain scores and percentages, please take a step back.

It’s important to remember that conferences are a two-way conversation. Show that you care by asking questions and listening to answers. While parents are learning how their children are progressing in school, you want to learn about their home and community lives. Parents often know student strengths and weaknesses, and learning styles. They can identify possible future problems. When mom says, “Don’t let her sit next to Marisol,” that’s good advice. While the emphasis of a conference should be on learning, social and home factors affect learning at all levels, and parents know your students’ lives. If Mary seems distracted, explore the problem with her parent(s). Is she sleeping enough? Is she having social difficulties? Has she seemed more distracted lately? How much time does she spend gaming in the evening?

The tone of parent–teacher conferences should be determined by students’ needs. In all cases, you will want to lead with the positive, whether that’s a well-done assignment or a funny story. For students who are doing well academically, you will wish to point out areas where they might strengthen performance. What can Jimmy do to become even better in math? The Jimmy conferences tend to be fun and easy.

The real challenge of conferences rests in discussions with parents of struggling students. I have always had trouble striking the right balance when talking about these students. If you are like me, you will want to be optimistic about Nolan’s behavior or Mary’s academics. You will want to emphasize the positives. For students who are genuinely struggling, you must take a more somber tone. I have sometimes downplayed my problems, spinning them for myself and for parents. I should not have done so.

While parents should hear the good, they also deserve to get the full picture. I suggest a “just the facts ma’am” approach. Instead of saying, “I know Mary has been distracted by her new baby brother, but she is not turning in some of her assignments,” eliminate any excuses, explanations or rationalizations you might be about to offer. Instead simply say, “Mary has not turned in six of the last ten assignments.” Then go from there to create a plan to fix Mary’s problem(s). Softening the blow does Mary no good.

Excuses, explanations and rationalizations never helped anyone get ahead in work or life in the long-run. Mary needs to do her work. Her parents need to understand that she is in trouble.

Some teachers naturally know how to handle the difficult conference. I had to work at that skill. If you tend to err often on the side of kindness, please keep in mind that parents may take you at your word. If you say, “Nolan will probably grow out of it,” those parents may wait for Nolan to grow out of “it” when they should be aggressively working on changing a behavior or finding him a tutor.

Other tidbits:

♦ Bring granola bars or snacks for yourself. You may be running for thirteen hours straight through.

♦ Dress professionally. Some teachers go for business casual, but I’d suggest notching it up a bit. On this one day, put on heels. (Unless you are a guy, although if you are a guy who wants to wear heels, that’s certainly your business.) Throw some tailoring into whatever you decide to wear. You are probably making a first impression.

♦ Bring crayons and toys for little brothers and sisters. Have books or magazines handy for older siblings. You might lay in chips and snacks for the kids.

♦ Try to stay on schedule. Some parents have multiple conferences to attend or evening jobs. Those parents may not have an extra fifteen minutes to wait in the hall.

♦ Be ready with advice. If Mary seems distracted, be ready with suggestions that may help her. Tell parents you will try moving her away from kids who distract her. Ask if parents could put her to bed earlier. Suggest shutting down the gaming system at a certain hour or not allowing gaming until all homework has been finished.

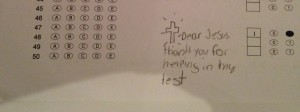

♦ Be Prepared for Surprises. Parents say the darnedest things. A mom I knew once said, “Maybe she’s just dumb. Her dad was dumb as a post.” Uhhh… It’s hard to know where to go after a comment like that. How do you respond? I’d say stick to the positives. Steer mom toward tutoring while observing that her daughter works diligently in class.

Eduhonesty: Do you have enough to do now? Are you thinking there may still be time to go into accounting or banking? I have one last piece of advice.

Your mission, should you decide to accept it, Mr. or Ms. Hunt, Phelps, Briggs etc., is to call or write home. If you want to raise parental attendance, a personal invitation works wonders. In districts where parental attendance is light, this one step can cause the number of parents at open houses and conferences to skyrocket. I know this may all sound like a mountain of work, but getting parents in for conferences will help you all year long. If you do have to call home later because of academic or behavior issues, that personal relationship goes a long way towards helping you to help your students.