An unfortunate irony should be mentioned here. I live in a district with two superb high schools. Despite sometimes failing to hit NCLB test targets, Glenbrook North and Glenbrook South aren’t being hurt by their numbers like the schools in North Chicago, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland and other academically- and financially-disadvantaged areas. The Glenbrooks know the government won’t come after them: The embarrassment for state and federal education officials would be far too great. Even a cursory glance at the schools’ academic performance shows both to be among the best schools in the country. Like other fortunate schools, especially in wealthier parts of the country, the frantic, ongoing attempt to push up test scores does not impact these schools with the intensity that it impacts lower-performing schools.

Those fun elective classes that students most enjoy? Schools like the Glenbrooks commonly provide a wide variety of such electives, electives that are seldom being used for extra math minutes, English essay practice or their equivalents. The Glenbrooks must do test preparation, of course, but they know the state will not dissolve their school or take them over. They don’t have to put frantic energy into figuring out how to fix the numbers. They are “safe.”

I believe one effect of NCLB and the subsequent, laser-like focus on standardized tests has been that advantaged schools, those schools which in the past were able to provide more enrichment options and more fun afterschool activities than less prosperous counterparts, now are often providing proportionally even more enrichment and more fun options than their less wealthy counterparts.

In poor and urban schools, especially, the need to improve test scores may shove enrichment and school-spirit issues aside. North Chicago High School is trying frantically to improve test scores, despite an overall lack of resources. The high school recently stopped allowing students to start French and eliminated woodworking. No electives remain except NJROTC, fine arts and Spanish, and what music one music teacher can offer, along with Consumer Math and a few business courses. Fine arts and a foreign language are the two electives necessary for many college applications. Currently, the staff directory lists one music/drama teacher, one business teacher, two NJROTC teachers,three foreign language teachers,and two fine arts teachers, one of whom recently left her position. Spanish has become the only language.* NJROTC has manages to stay in the game since students and administrators in financially-disadvantaged areas often see the military as a path out of poverty.

In the meantime, seventeen miles north, in a much larger and wealthier district, we find the following on the District 225 website:

To create a comprehensive high school experience, the Glenbrooks focus on three distinct areas: Academics, Athletics and Activities. Academic success is a top priority for our students and with almost 300 diverse course offerings, there is plenty of opportunity for exploration. In addition to core academic courses in the areas of English, mathematics, science, social studies, and world language; students may pursue special interest classes such as debate, architecture, automotives, and graphic design.

Glenbrook students enjoy success inside and outside of the classroom through numerous athletic and activities programs. The schools offer over 25 different competitive sports and a series of club sports to satisfy any athlete. Each school also hosts from 70-80 different clubs and activities for students throughout the year.

By the numbers:

- 4,823 Students

- 849 Employees

- 40+ Different dialects

- 25.3 Average ACT score

- 96.8% Graduate rate

- 96% Enter college post-graduation

- 300 Course offerings

- 70-80 Clubs and activities for students

- 25+ Competitive sports

- $110M Annual operating district budget

I found the following on the District 225 website as well, under new courses proposed for 2014-2015:

In January, the Board of Education approved new courses recommended by the administration for the 2014-15 school year. Glenbrook North The Career and Life Skills department added a new series of Project Lead the Way (PLTW) courses, designed to meet the needs of students pursuing studies in engineering and technology-related career paths. Four honors courses have been recommended including: Intro to Engineering Design, Principles of Engineering, Civil Engineering and Architecture, and Engineering Design and Development. Glenbrook South The Applied Technology department added two honors PLTW courses to its existing engineering offerings, to complete the four-year sequence. Civil Engineering and Architecture will add an architectural component and Engineering Design and Development will serve upper classman as a capstone course. The business department added Investment Strategies, a course designed to help students develop wealth management, investing, and financial planning skills. The Physical Education department added Weight Training and Conditioning II. The Science department added Honors Physics and Astronomy 171, an option for students electing to earn honors credit.

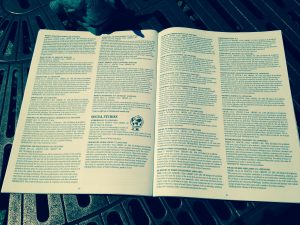

I can scarcely begin to convey the differences between these two districts in a blog post. I would be typing for hours if I tried to list all the Glenbrook electives and clubs. I have a student/parent handbook from a few years ago with a curriculum guide that runs 24 pages.

Here is a sample (click to enlarge):

Here is another sample:

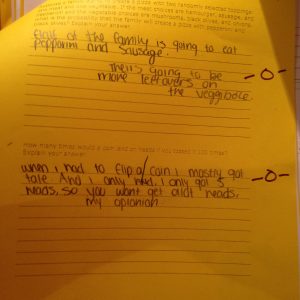

In the meantime, for all intents and purposes, I’d say that North Chicago High School barely has electives. If you don’t want Spanish, fine arts, NJROTC or classes with that one music/drama or business teacher, what can you “elect”? Woodworking used to be a student favorite, as was a radio/TV broadcasting class, but those classes are gone. You can still do radio/TV broadcasting, but not for credit.

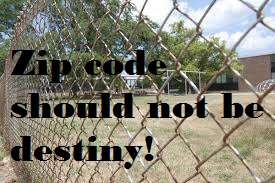

Zip code should not be destiny, but anyone who thinks that zip code cannot become destiny has fallen down the delusional rabbit hole as far as I am concerned. Can students triumph over schools that do almost nothing except prepare them for an annual test? Yes, students from these schools go to universities sometimes and succeed. But those kids who live in a district with an average ACT score of 25.3 have a far greater chance of succeeding in college than the kids from a district that received an average ACT score of 15.6 in 2014. The ACT itself defines college readiness as a score around 21. (http://schools.chicagotribune.com/school/north-chicago-community-high-school_north-chicago).

A natural gut response to North Chicago’s 15.6 average ACT score might be to say, “That school has to raise scores!” Yes, it does. But cutting down electives in favor of more time on core academics may do more harm than good to North Chicago’s students. Those lower-scoring kids need classes that interest them. Some of them might love to take Astronomy, Intro to Engineering Design or Investment Strategies. That 15.6 average tells a backstory, one with many apathetic and lost bodies occupying classroom desks.

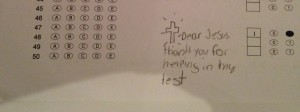

First, you have to care. If students can be convinced to care about the academics in which they are immersed, higher scores will follow. If they don’t care, three hours of mathematics may not do much more good than a single hour. Learning is never a passive activity. Engagement will always be a key piece. Content and student areas of interest directly affect student engagement.

When the whole focus of instruction becomes the test, the test, the test, what hook do we have to pull students into the fun of learning? What motivation are we providing for paying attention and participating in class? What motivation are we providing for going on to college?

Many kids in our least financially-advantaged districts do not know what college is like, or what college can be like. I once had a high school student say to me, “No way am I going to college. No way will I sit through four more years of social studies.” We try to explain college at college fairs, but the only experience some kids can use to understand college is the high school education they are presently receiving. Especially in this time of sometimes incomprehensible, mandatory, lock-step, Common Core lessons, I can certainly see why kids might say, “Nope, I’m not going to college. I am done with this stuff.”

*A quick acid test of a district’s schools for people who might be moving: What languages does that district high school offer? Scratch any districts that only offer Spanish off the list immediately. I’d consider three languages to be a minimum. A commitment to diverse learning opportunities can be captured in a snapshot of language learning options. The Glenbrooks offer Russian, Mandarin Chinese, Latin, Spanish, French and Hebrew, for example.