The article is titled, “Surprise! Beer Makes You Happier, Friendlier,” by Mary Elizabeth Dallas of HealthDay Reporter, and can be found at m.webmed.com.

Surprise!? Why I am shocked — shocked, I tell you — that beer makes people happier and friendlier. This stunning result comes to us courtesy of Swiss psychopharmacological researchers. They discovered that beer makes us happier, friendlier, less inhibited, and apparently even sexier. My own research suggests that “sexier” may only work when both members of a pair are drinking. Further research should be conducted to confirm my observation.

I like the fact that these findings were actually published in the September 19th journal of Psychopharmacology. The results will be presented in a few days at the annual meeting of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, as researchers gather in one of my favorite European cities, Vienna, Austria. I bet gallons and gallons of beer will be tested at that conference. Research on hard cider, screwdrivers and raspberry lambic will not be far behind.

Eduhonesty: I did laugh as I read this article. Sign me up! I don’t want to drink the placebo, either.

But I saw a message for teachers in this article. Administrators today often want teachers to use techniques tested in academic research that may not apply in all situations. Yes, Think-Pair-Shares may have worked great in that urban school with the extra teaching assistants and talkative students. But I worked under a principal a few years ago who wanted all classes to be doing think-pair-shares regularly and I quickly realized something that my principal did not seem to grasp: Think-Pair-Shares work poorly in bilingual classrooms, especially when too many students have reached the well-documented silent period. Bilingual students often shut down verbally when they become good enough to hear the small mistakes they are making. They stop talking because those mistakes embarrass them. Eventually, as their comfort level and language skills rise, those students will rejoin the conversation, but until then think-pair-shares become think-pair-try-to-get-the-other-guy-to-talk. If neither partner wants to talk, then another version may be think-pair-try-to-avoid-the-teacher-you-go-to-the-bathroom-first.

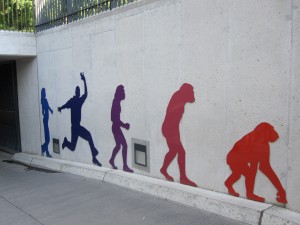

I may publish related educational tips shortly, but for now I want to reiterate a point I made recently: Look around the room. If that technique from the latest professional development does not seem to be working, go back to the drawing board. Will it help to shift kids around? Will different materials work? Do you need to drill expectations again? Shifting the pieces around the game board may solve your problems. But if you keep trying and trying, and your new technique does not seem to come together, consider the beer experiment.

Not all research represents new, groundbreaking insights that lead to methodological improvements.

In fact, some research qualifies as just plain silly, although I’ll be happy to write the pear cider grant application. Using surveys, I propose to study whether pear cider with semi-soft cheeses produces greater levels of happiness than pear cider with chocolate-covered nuts. I may have to expand my research to include pizza combinations.

I expect my research will take years to complete, but I feel the need to sacrifice myself for the good of science, like those noble folks in Vienna.