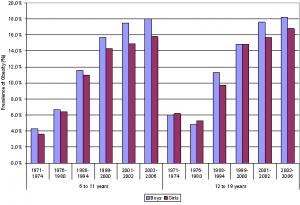

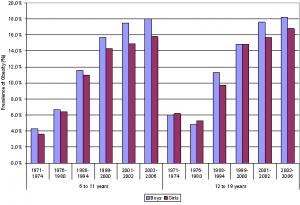

(Click on the above graph for a better view.)

All my friends drank Coke, Tab, Pepsi, Dr. Pepper, Bubble Up, Sprite and 7-Up. We drove to Baskin Robbins for hot fudge sundaes as soon as we got our licenses. We ate macaroni made with Velveeta cheese, garnished with cheap wieners, as well as bacon and stacks of pancakes for Sunday breakfast. We scarfed down buttery, salty school lunches until we became old enough to walk three blocks to the local drive-in for burgers and fries. I guarantee my high school only served organic produce by mistake.

I fell into those short bars in the graph above, though. In fact, all of my friends were part of the short bars. Obesity was rare in my high school and in colleges I intended. At the time, the female obesity rate was running five to six percent, and the male rate less. But we went to the beach on our days off. We played tag, Red Rover, and Mother May I. We played four-square and hopscotch. As we became older, we exercised in physical education daily and we were not allowed to sit out activities without a doctor’s excuse. We walked to our friend’s houses. We went hiking. We carried our rackets to free tennis courts in local parks.

Eduhonesty: I am not against new, healthier lunches, despite sometimes negative posts on this issue. I am absolutely against lunches that consist of tiny, single chicken legs, tasteless brown rice, and boiled, bland carrots. Organic or not, those lunches lack the calories growing children require. They also encourage crazy snacking when kids get home.

But I can get behind tasty, healthy lunches with enough calories for active kids. Give the kids two pieces of chicken and a warm roll or baked breadstick, along with spices or condiments for additional flavor, and I’ll mostly shut up about the lunches.

I will still be posting on this issue, though, because are attacking a serious, growing problem from the wrong direction. We don’t need less food. We need more exercise. America’s kids should be running back and forth across the soccer field, rather than testing how well they can think for a whole afternoon on less than 250 calories.

A study by University of Georgia kinesiology professor Bryan McCullick showed only six U.S. states require 150 minutes of elementary school physical education. Two states meet adequate middle school physical education guidelines, set by the National Association of Sport and Physical Education. NO states meet high school student guidelines.*

Many schools are eliminating or reducing physical education due to budget struggles and a desire to reallocate time toward academics. (Translation: P.E. and recess are being sacrificed to push up school test scores.) Yet we need those P.E. minutes desperately. As our kids hunker down over their electronics, we should be pushing them outside with bats, rackets, mallets and balls. We have to get today’s kids moving. Cutting calories and fat will create skinny kids but, without exercise, those skinny kids will not be healthy kids.

American should return to mandatory, daily P.E. for all grades.

*http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/07/09/study-school-based-physic_n_1659579.html