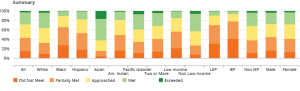

(Click to enlarge. We will need to add a few categories for ESSA.)

The more I read about ESSA, the more I mutter under my breath. We SO needed a new law that adds MORE data requirements for districts and then throws the creation of new exact details of testing to the states. ESSA touts the idea that educational control has been returned to states. Yes, and when the kickstarter campaign for my new elevator to the moon launches, I hope everyone believing that ESSA fiction will toss a few thousand dollars my way.

Taking a quick tally, ESSA did not decrease the number of tests required in public schools, although a few potential substitutions are allowed. ESSA did not decrease reporting requirements; in fact, the law added new categories to separate out such as homeless students, students in foster care, and students whose parent(s) are active duty military members. Additional reporting requirements for English learners have been added, in apparent hope of forcing schools to adopt more demanding performance expectations for their EL populations. ESSA also requires new data to be reported about school “climate” and safety, including data on school suspensions, expulsions, violence, and chronic absenteeism. Various other snippets of addittional data will be required as well, such as preschool enrollment.

Students are still expected to test in mathematics and English/language arts in grades three through eight and then once in high school. National assessments such as ACT or SAT will be allowed for high school testing provided these tests can be shown to adequately measure the required state curriculum. This data-driven requirement should shut down most or all attempts to create alternative assessments. Science will still be tested once in elementary, middle and high school. ESSA has kept the requirement for breaking down results by subgroups, as well as the requirement that 95 percent of students participate in state assessments, with student participation assessed as part of state report cards. Overall, the testing picture has changed little, a few brushstrokes at most.

Schools still must be identified for improvement. Specifically, schools where any student group* is consistently underperforming must be identified for targeted support and improvement. While states have allegedly been given flexibility in defining “consistently underperforming,” schools identified for support and improvement must create a plan to file with their local educational agencies (LEA). Schools can be identified for support and improvement if they 1) get Title I funds and score in the bottom 5 percent of a state’s schools, 2) Have a high school graduation rate below 67 percent, or 3) Despite lengthy time on a targeted improvement plan, still have one or more student group performing in the bottom 5 percent of a state’s test.

Would you like a cup of NCLB with your new law anyone? States are allowed to make changes to NCLB and NCLB-based provisions — but within a familiar test-centered agenda. Would you like more data with your endless data?

A few quick positives: Preschool funds have become more available. ESSA permits adaptive testing, such as the Smarter Balanced test, and will also accept out-of-level testing for high school mathematics in eighth grade. ESSA also makes changes to charter school policy designed to improve accountability in the authorization process.

Eduhonesty: More data = more lost time = greater opportunity costs. Data gathering is not teaching, but data gathering requires teachers’ time, time that cannot simultaneously be used to construct new lessons. Data gathering never planned a spirit assembly but data gathering has undoubtedly prevented many administrators from creating those assemblies or other student bonding activities. One fundamental problem with government educational initiatives has to be the stunning lack of concern for the time required to institute those inititatives, time that bleeds away, never to be recovered.

We might just close the achievement gap if we used the time we spend crunching numbers for spreadsheets to teach America’s children instead.

*In NCLB fashion, subgroups are broken down into major racial or ethnic groups, economically disadvantaged students, English learners, or students with disabilities.