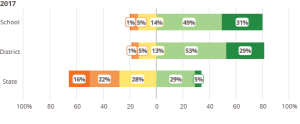

From a previous post: “80 percent of freshman entering community college in the CUNY system require remediation in reading, writing, math, or some combination of those subjects,” according to the New York Times.*

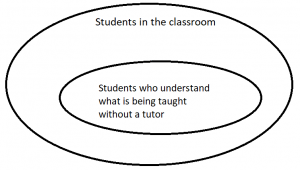

Who are these students who leave high school unready for community college? Who face possible extra years of remedial classes and college tuition before they can tackle “real” college classes? They are the high school graduates who spent most of their school lives in that outer bubble above, the kids who tuned out because they could not understand when they tried to tune in.

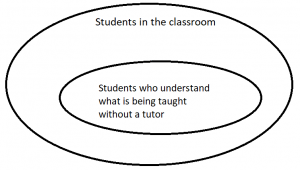

Education courses teach strategies to convince students to tune back in but kids don’t always respond. We teachers assign extra readings and cross our fingers that the readings will be read. We rewrite handouts to simplify the language. We rewrite chapters of the textbook. Some students do our modified homework, while others throw it in the trash. We call home to enlist parental support. We attend seminars to help us learn to do group work while keeping control of our classrooms, knowing that 8 groups of 4 adolescents can easily go from zero to chaos in 60 seconds, no matter how many strategies we learn. All it takes is one, loud put-down of a student’s sister or boyfriend.

Regardless of what we try, though, if our students are too far behind, we lose them. “You can do it,” we say. Whether they can or whether they can’t – and sometimes they honestly can’t – once a kid believes that he or she can’t, the game is over. “Try harder” may be intended as encouragement, but sometimes I’m sure it feels more like an exhortation to keep beating yourself up.

Some kids also believe they are fully capable of doing what we want, but decide to skip all that work and ignore boring adult demands. These students would rather send a few thousand photos and text messages, play videogames, or find other ways to screensuck their days away. Our best efforts combined with full parental support may not alter this addictive behavior. Even if dad or mom takes the phone away, and monitors computer time, students today can find other electronic outlets to replace schoolwork and homework. My daughter used to role play in a “live” computer game online with a girlfriend. They would sit at different computers, sometimes but not always in the same house. Both girls successfully navigated college, but games can easily supplant academics and social interaction. The homework simply does not get done. Studying does not happen. At worst, students skip classes, and even miss midterms or finals. Not all students manage to catch up later.

Whether students can’t or won’t do the work expected of them in class, the effect is the same. Students graduate high school unready for the challenges of a college curriculum. They can’t go forward without a lengthy, expensive detour. They can’t go back.

What not enough politicians and administrators seem to recognize is the extent to which current testing policies contribute to the academic problems and challenges facing America’s schools.

I’ll ask forgiveness for broadly simplifying factors that create my outer bubble above, but let me break down one more toxic effect of testing: 1) All students are expected to take the same annual test on which their school will be judged, regardless of their academic or linguistic competencies. 2) Because of this fact, the curriculum is built with the idea of making certain that all test categories will be covered in class before the test. Teachers may even end up obliged to use identical lesson plans throughout the year. 3) Once all classes are teaching the same material, classroom placements become far less important than in the past. Those placements may even be made alphabetically by a computer. As a result, Sandy reading at a 2nd grade level ends up in class with Marianne who reads at a 8th grade level.

And therein lies the problem: When we put six or more years of difference in levels of academic understanding in one room, we automatically build that outer bubble above, the students in class who don’t understand the work. Teachers are supposed to differentiate to solve the challenges created by our broad range of learning levels but, especially in districts with limited resources, that differentiation may not be enough to fill in the gaps and chasms. Many students who have fallen years behind the pack naturally don’t do expected classwork. Some don’t even open their book by middle school and high school. If a classroom contains enough of these students, after awhile other, more capable students may begin skipping homework and slacking off on classwork. For one thing, those students in the outer bubble can be pretty distracting. For another, teachers often relax homework rules once homework compliance becomes problematic enough, allowing late homework in hopes of getting back more homework.

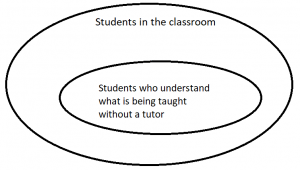

Struggling schools may even mandate a relaxation of traditional homework rules, requiring that teachers devalue the weight of homework in final grades and accept late homework until the end of the semester. Across America, school districts have begun trying out a grading system where no score falls below 50%. Students receive 50%, whether they turn in the classwork and homework or not. The last two districts I worked in both flirted with this system. The rationale behind this grading system lies in a desire to keep students engaged in school. If students fall too far behind, administrators explained in a staff meeting I attended to introduce the new grading system, they will not be willing to try to catch up. They must have a chance to succeed. At 50% minimum, everyone has a chance to “succeed.” Under this grading policy, any student who hacks out an occasional assignment can at least pass. Whether that represents a “success” or not seems debatable. But the 50% floor for grading does prevent “F” grades. It particularly benefits those who can’t or won’t do their homework, at least if we define “benefit” as “allowing students to pass whether they have learned anything or not.”

In earlier times, we might have removed students from classes where they were unable to do the homework. When students could not handle Honors English, they were placed in regular English. Larger schools created different “regular” English classes as well, grouping students at the start of the year, allowing materials choices that would be appropriately challenging to the bulk of students within the class, given their documented academic understanding.

Now, too often, screening and differentiation are skipped when administrations fill classes. Instead, teachers are told to differentiate within the classroom. What too often results is an academic free-for-all in which our 8th graders who read at a 9th grade level carelessly dash off homework, sometimes with extension problems to challenge them, while especially lost 3rd grade readers toss that homework on the hallway floor on their way out of school. Special education and bilingual students may be lucky enough to receive help from a resource teacher assisting the regular teacher, but even then, these students may be unable to understand the textbook the class is using.

School districts build at least some of the outer bubble in my graphic organizer because of testing demands. Why do so many New York high school graduates remain unready for community college? Testing and related-data demands have fostered a standardization of instruction that fails to meet the needs of students too far from ready for their year’s state test.

Eduhonesty: Yes, teachers always can and should differentiate. But my last administration put so many limits on remediation in an effort to make sure that all the topics expected to be on the test were covered that almost no time for remediation remained. Differentiation requires remediation. Remediation requires curricular flexibility. When the teaching to the test destroys that flexibility, students who missed material in earlier grades may never see that material. The result can be seen in my bubbles.

The results can be seen in those remedial math and English classes that pepper the hallways of the New York Community College system.

The results can be seen in those remedial math and English classes that pepper the hallways of the New York Community College system.

*CUNY to Revamp Remedial Programs, Hoping to Lift Graduation Rates, Elizabeth A. Harris, March 19, 2017