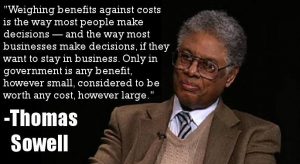

I sent my eldest to grab some hair ties for me at Target. She came back with about 40 of them, all black. I’d have chosen differently, but so what? I simply said thank you. I now have an abundance of plain, black hair ties. They work fine. When the stakes are low enough, unexpected or even wacky choices don’t matter. As the stakes go up, though, choices should receive consideration and scrutiny after the fact. I’d suggest that where educational policy is concerned, choices should even carry with them evaluation periods and pilot programs.

Learning standards. The words sound so simple, so innocuous — the Common Core Learning Standards. Our shift to the Common Core standards has been sucking up enormous amounts of time and money — and will continue to do so. Shifting away from those sometimes unfortunate standards will require even more time and money. New standards require many meetings and professional developments to teach to educators, as well as new lesson plans, new lesson sequences, and often new books and software.

“Bad news for supporters of national education curriculum: States with education standards most closely aligned to Common Core fared worse on math tests than states with their own standards, according to a new study.” http://dailycaller.com/2014/03/18/common-core-gets-awful-review-in-new-study/The study, conducted by the Brookings Institution, compared standardized test scores for all 50 states over the last five years. It found that states using education standards that are most dissimilar to Common Core tended to score the highest on math.

Check out http://www.nationalreview.com/article/373840/ten-dumbest-common-core-problems-alec-torres for a little graveyard humor on the Common Core standards.

[1] I don’t know whether to hope the Common Core survives this administration or not. The Core has serious flaws in my view, especially in its non-research-based expectations for students in earlier grades and lack of planning for alternative high school programs beyond the one goal of college, college, college. But rewriting all those standards and making everyone drop everything to learn another new set of standards… Again! …Aaghh. We would probably minimize our pain by fixing the Core, rather than creating yet more standards. The whole situation reminds me of a North Shore remodeling run amuck, where a too-wealthy, too-bored trophy wife keeps changing her mind about floors, fabrics, paints and lighting until nothing works and nobody knows what to expect. We don’t need to create the perfect standards as much as we need to find a good set of robust, adaptable standards that we can and will stick with – allowing for much needed continuity of instruction. The Core has played hell with that continuity, incidentally. That’s a major part of the reason my students were drowning that last year.

I don’t know whether to hope Trump succeeds in scuttling the Core.

Changing learning standards should never be taken lightly.

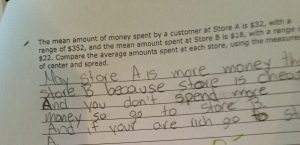

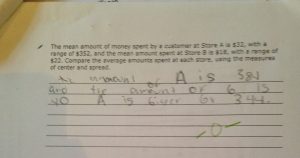

Eduhonesty: The above is a picture of an obligatory, standards-based test given to a student who should never have seen that particular test.

Eduhonesty: The above is a picture of an obligatory, standards-based test given to a student who should never have seen that particular test.

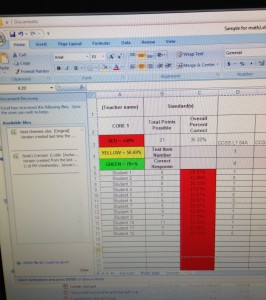

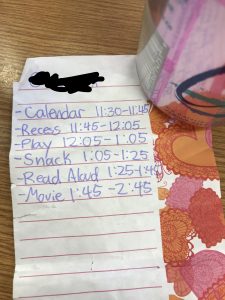

I actually got this as a sub plan. This is not a sub plan. The kindergarteners and I had a fine time but …

I actually got this as a sub plan. This is not a sub plan. The kindergarteners and I had a fine time but …