2014 unit test.

2014 unit test.

Returning to a time when I taught bilingual Language Arts and Social Studies:

During the 2011 to 2012 school year, I did what I was supposed to do. I worked in teams. I adapted the lesson plans of other teachers and taught what they taught when they taught it. I explained the difference between legend and myth when other teachers explained the difference between legend and myth. I presented the Battle of Shiloh when they presented the Battle of Shiloh. Of course, the bilingual students were always barely keeping up with the “regular students” at best. I was sometimes rewriting whole chapters of the social studies book.

All my required textbooks were difficult or even impossible for my students to read, including parts of the Pearson English-language learner version of the language arts textbook. My students were not much interested in the Pearson books’ stories [1], but that fact was not my greatest problem, although lack of student interest complicated my daily teaching life. Some of my bilingual students had told me they did not intend to finish high school. I would have liked to be allowed to prepare lessons to inspire those kids to stay in school, even when those lessons did not match everyone else’s plan, using my own book and story choices.

My students and I had a much larger problem than in-sync lessons and interest in school, however, captured in a distressing moment during one of the almost daily afterschool staff meetings. We were grouped together to discuss the “cusp” plan in which we identified students who were nearly able to make targets on the annual state test, focusing our tutoring efforts on those students in an effort to bring up the school’s overall scores. For example, a MAP® score of 213 in language arts might indicate a student was probably only slightly below the level needed to pass the annual test, the Illinois State Achievement Test (ISAT) at that time. We were to give cusp students more-intensive, small-group instruction during tutoring, hoping to get them across the passing line for No Child Left Behind purposes. The cusp plan had solid potential to pull scores up, saving our school and district from government sanctions.

Unfortunately, my tutoring period was the only time I had to work on targeted English instruction tailored to my students. All the rest of my classes were taken up doing required versions of other people’s lesson plans. I asked the Principal if I could send the four to eight students in my cusp group to another teacher for their small-group work. A fellow language arts teacher — Thanks, Nicole, across the years — said she would take my students.

The Principal looked upset.

“That’s what (the 8th grade ELL teacher) said too!” he replied angrily. “I don’t think I like it.”

I have profound respect for that Principal. He’s a great administrator, the best I’ve ever known. But by that time, he’d been up against the wall for years. Those scores had to come up or else. We were getting closer to hitting the ugliest of ugly NCLB sanctions by then – the takeover of our school by the state. But the kids in my bilingual classes had entered middle school full academic years behind grade level, and attempts to pull scores up were being seriously complicated by state and Regional Office of Education involvement, the involvement that led us all to teach the same stories from the same books that my students did not like.

I looked at my irate, frowning Principal and tried to clarify the issue.

“When are they going to learn English?” I asked plaintively.

I kept asking for time for English. He kept signing off on this but tutoring kept filling up with required behavioral modification strategies to work on, assemblies to attend, schoolwide test preparation sessions using a common book, as well as regular practice and benchmark tests of one kind or another that preempted tutoring activities. The teacher next door, imported from Spain, was also doing a remarkable job of small-group work in mathematics. I kept clearing his path, making sure he could use tutoring for mathematics, often at the expense of English, since there was only one 40 minute tutoring period daily, and those small math groups could not use it for English. If students emerged from the year understanding the mathematical order of operations and how to manipulate fractions and decimals – well, that had the potential to be a real win, even at the cost of the little time I had available for English-language instruction. (Some students made formidable mathematical progress that year thanks to Francisco, who regrettably returned to Spain. A couple of years later, a few were in regular honors math classes at the high school.)

Students were either in math or English during tutoring, also called Response to Intervention, or RtI. With selected students doing math or English in small groups, that left a large group to do English independently. The small math and English cusp groups varied regularly, making it difficult to continue in a linear fashion on any topic. Some students on the cusp in English had also scored on the cusp in mathematics. Francisco was taking students based on their need to learn parts of the math curriculum, so his groups might change from day to day. Some students started with me on a topic, but then missed the end.

My bilingual students needed a great deal of pure English instruction if they were ever going to pass the annual bilingual exit test, but under that year’s regime, I was mostly forced to put them into groups to work by themselves on flash cards and vocabulary. They could do vocabulary independently. That freed me to work with the students in my English cusp group. I cheated and stuck a couple of students in the cusp group whose scores did not quite meet the numerical cut-off. Even with those extra students, I was focusing on 4 to 8 students (numbers varied depending on how many kids Francisco had taken) who might make annual state test targets, a rather unlikely prospect for even this small group given that these students had never been able to pass the ACCESS English-language learning test.

My life was complicated by books and materials purchased by the District Bilingual Coordinator. She expected me to take advantage of these extra materials. I managed to use my off-script books for independent reading for non-cusp tutorees, but there was no time to take advantage of these books and supplies otherwise. The school’s administration required my classes to use recently-purchased Pearson materials instead. We were perpetually behind throughout the year, fighting language deficits that needed to be addressed while keeping up with all the other teachers in the school.

I used the SIOPTM lesson plan model[2] to work language learning into my content-based lesson plans. In theory, this lesson plan model helps ensure both curriculum content and English are taught to English language learners. It’s sound practice in the right circumstances, but we were being overwhelmed with unfamiliar content as we tried to march in step with the “regular” classes. In social studies, I was explaining the American Revolution to students who were not from this country, and who did not know if America had started with a bang or a whimper. Unlike regular students, some of my students had almost no background knowledge of American history. History can be a tough sell no matter where a kid was born. At least the revolution and the civil war had fighting. I kept a number of the boys listening by discussing general military tactics and applying these to specific battles.

Why all the above details? I picked up a favorite saying during professional development: “There is no teaching without learning.” During this year, I experienced its corollary. I feel silly even writing this, but what I learned is that “there is also no learning without teaching.”

I had no time to teach English and, as a result, the ACCESS scores came in showing virtually no progress in English, with a motivated exception or two. The students who actively asked for help filled in gaps. The others went nowhere. I wish I were more astonished. I wish I did not feel that I had wasted so much of that year. The truth is that in a few years, these students won’t care about the difference between myths and legends and a number won’t remember who won the battle of Shiloh.

I taught content and vocabulary related to that content. I taught the curriculum. But the curriculum was not what these students needed. They needed basic English. They needed to work on irregular past-tense verbs. Some of them needed to work on regular past-tense verbs. (Quote from a favorite seventh grader: “Ms. T! The boys dooed something bad!”) They needed to learn English-language word order. They needed a great deal more basic instruction in the primary language of this nation than they received, due to pre-established administrative plans designed to pull up test scores that stole away almost all the hours and days of our time.

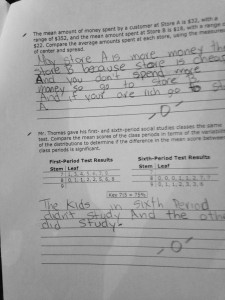

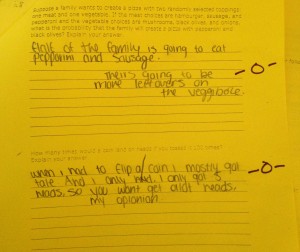

Eduhonesty: Strike two against the Core and bilingual education as currently practiced. While the Common Core was not impacting my classroom during 2011 to 2012, the homogenization of education resulting from the Core has only worsened teachers’ situations. During 2014, the year before I retired, I was required to use tests and quizzes based entirely on Common Core expectations. I could prepare almost none of my own materials; outside consultants chose materials and unit tests for me, few of which my students could read.

Not a single student of mine passed a single East-Coast prepared unit test all that last year. I showed pictures of the tests to a community college professor this week, who understood immediately:

“They could not read the tests,” he said.

No, they could not. But absolutely no one listened to me anywhere up the line while I tried to point out this rather important aspect of my testing situation. “No excuses!” My assistant principal kept repeating. Not being able to read the test was no excuse. I am not sure being dead would have been an excuse.

[1] That ELL book from Pearson did have stories that my students might have enjoyed but other teachers were picking my daily reading choices. The story about the scared, young African-American boy in the stairwell may have captured the imagination of many students in my school. My students struggled to relate to the setting, characters and plot, however, none of which resembled their own lives. At that time, the school was about one-half African-American and one-half Hispanic, an atrocious set-up for one-story-fits-all, especially if a school is trying to make those stories contemporary and “relevant” to students’ everyday lives.

[2] The Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOPTM) Model is an instructional model used to create lesson plans that meet the academic needs of English learners. The model can be used to build robust, language-centered lessons in any content area. I will recommend SIOPTM to teachers in all subject areas.