In this time of quantification, the unquantifiable tends to get lost. If no sources and numbers can be offered, a concept may disappear from view. Stakeholders and others argue at length over the meaning of test score results. They argue much less over the effect of those results on individual children. An emotional trait that cannot be pegged with a number, predicted or put into a formula becomes invisible. Districts are working to improve attitude with positive feedback and mindset training, but the emotional lives of students remain a gray area only sometimes allowed to fall into education’s orbit.

Here’s one elephant hiding in the room with us: Those tests and test results? Their weight, their gravitas, has been increasing over the years. Fifty years ago, students were taking an annual spring test. But scores were simply much less important. Kids were not hearing about that test all year long. They were not having their faces rubbed in past results. Mostly, we were leaving kids out of the process.

The tests were adult territory. Just as alcoholism, sex, family financial difficulties and gory news were not shared with children, school leaders were not regularly taking children aside to tell them that their lack of academic prowess might condemn them to a botched and futile future life. For one thing, many more vocational options existed in those past schools because the idea that all students should go to college had not yet taken hold. We were measuring kids, but we were not trying to whip them into frenzied test preparation.

Once, the goal of instruction was learning. That may still be true, but not all U.S. students know their school experience is a voyage into learning. Actual classroom quote from a late spring day, some weeks before the end of the school year: “More math!? Why do we have to do more math? The tests are over!”

What is the effect of this changed emphasis on the importance of testing? A line from a song captures what I suspect: “Wake up each day with the weight of the world spreading over your shoulders. Can’t get away from the weight of the world crushing down on you … and you’re afraid it’s gonna go on forever.” (Lowen and Navarro).

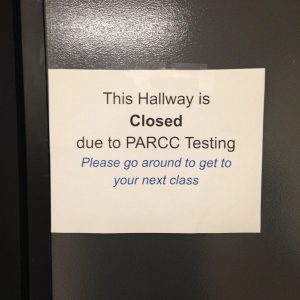

I think this piece of the puzzle just gets lost. Before NCLB, before the fierce emphasis on data, we did not involve kids in our desperate data quests other than to hand them a test to complete. Now we hold conferences with them after tests to ask them what they think their test scores mean, where they think the test went wrong, and what they think they can do to improve future results. I was required to sit down with each student to go over MAP benchmark tests during my last formal teaching year, and I am sure we would have done the same for the PARCC test if those results had come in before the end of the school year.

Let’s just rub everybody’s noses in their “failures.” That will get results. What results? I’d say that’s the elephant.

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) diagnoses have skyrocketed in the last few decades. According to https://www.healthline.com/health/adhd/facts-statistics-infographic#demographics, the CDC says that “11 percent of American children, ages 4 to 17, had the attention disorder as of 2011. That’s an increase of 42 percent between 2003 and 2011.”

But here’s my scary thought: What if at least some of the growing ADHD is not ADHD? What if we are seeing Generalized Anxiety Disorders instead in students who cannot hit targets, sudden trials that keep popping out at them like black-and-white images of human targets on police firing ranges? That woolly-headed, pinging-off-the-walls behavior often called ADHD? It can be ADHD — or it can be anxiety or a nightmarish combination of both.

What if some of our children are simply buckling under the pressure?