Shasta – a 40-lb. giant, invisible slug wearing a pink cape that covers her body and spreads out in soft folds around her. She has on her favorite gold-sequined top hat with a pair of large, black lunettes (sprinkled with clear rhinestones) that extend out from the brim, hiding her eyestalks. She is floating on a pink-and-cream-flowered bathmat, about four feet off the ground, to the left of mommy, who sits at the computer near the big bay window with the dark brown curtains.

Mommy – A former teacher who is in yesterday’s gray sweatpants and coral t-shirt. Her brother drove away with the rest of her clothes yesterday.

______________________________________________________________________

Shasta: Can we have more Costco chocolate muffin?

Mommy: Half a muffin is enough. We’ve already maxed out our annual allotment of Coffee Mate French Vanilla Creamer for the year and it’s Day One of Visit to the Elderly Hoarder Parents, who have at least one roach and one rustling creature.

Shasta: There’s never just one roach, mommy.

Mommy: Smart girl. And my Aunt Delois may really have had a weasel in her house. But at least it doesn’t sound like wild kingdom here. Cleaning starts soon. I could use my brother. Not to mention my suitcase. Brother or no brother, we clean, though.

Shasta: I thought we were going to talk about education.

Mommy: We are. I want a big picture.

Shasta: How about the one with the big, red sail on the right. This place is loaded with big pictures. And small pictures. And teeny pictures. And all the other pictures. Mommy, I bet we can find over 10,000 pictures in these two rooms right here.

Mommy: Maybe, but I want to capture how education fell apart in one page or less. This is a metaphorical picture.

Shasta: We don’t need any more pictures here, that’s for sure.

Mommy: Shasta, stay focused.

Shasta: Why?

Mommy: (Sigh.) O.K., the doors are open now, to quote my favorite zombie trilogy of the moment. The phone is dying, the charger in Seattle, the car dead, and my body’s still on Illinois time. We are falling off the grid with nothing to do but clean. You know how I love cleaning. When will we have a better shot at this?

I really loved the part where the plane landed, I got together with my brother, we went to our favorite used bookstore first thing, found great books and happily came back to the house. Then we completely forgot all my earthly goods – I had books, right? What more did I need? – and he spirited my life in the green suitcase away to Seattle.

Shasta: (Hopefully) Maybe some of that chocolate cereal?

Mommy: (Sigh) You can get lost in the facts, Shasta. That’s the big problem. It’s easy to get lost in the facts. So many facts. So many factors. This isn’t that elephant with the blind men in the fable. It’s more like a centipede.

Shasta: The blind men would just crush the poor centipede. You don’t want to be a bug around blind people, mommy . Though that might be safer than being a bug around sighted people, when you think about it.

(Shasta thinks awhile.) She finally solemnly announces: Don’t be a bug, mommy.

Mommy: Fine. I won’t. Now back to education. It’s not the tests. The tests are mostly a symptom.

Shasta: (Doubtfully) The tests cause lots of problems.

Mommy: But where do the tests come from?

Shasta: The center of the Earth? You know, the Common Core.

Mommy smiles.

Mommy: Let’s list symptoms and see if we can work back to the ailment. We test and test. We go to meeting, meeting, meeting, meeting, meeting. We rewrite curricula, mostly to get to the Center of the Earth. We give kids crazy tests they cannot even read. Then we make spreadsheets that document their inability to read the test that we knew they could not read before we even handed out the test. We try to tutor them a little during the year, but mostly we don’t have money and many of them choose to take the bus home instead anyway. Then we release them for the summer so that can forget most of what they managed to learn, while we gave them material on the spring test instead of the material they had missed during earlier years. What did I leave out here?

Shasta: (Helpfully) Sometimes we use the teachers to tutor the kids who are behind when nobody’s around to replace the teachers. Then the students who are not behind end up with study halls and get to hang out and text with friends. I think you mostly got it, though, mommy.

Mommy: To ask your question – why? Why are we doing this?

Shasta: Education is the new civil rights, mommy. We want to close the Achievement Gap.

Mommy: But I think we are making the gap worse, Shasta. Look at the State of Illinois Interactive Report Card. Where are the improvements? We have made some small progress, but since we are spending the whole year trying to teach academically-underachieving students how to take one test, we damn well ought to have some progress. Are these kids any readier for college?

Shasta: I don’t know.

Mommy: The scary thing is, I don’t know either. What we need to understand, Shasta, is we are not talking differences in degree. We are talking differences in kind. When we forgot Vygotsky and Piaget, and their work on child development, we gave up the game. But we sure can spin wheels. Sometimes I think advanced education in the field of education may be turning people into hamsters.

Shasta: Diabolical.

Mommy: Indeed. No small part of the mystery rests in the hamsters. So many intelligent people go into education, so many want to help. But just as MBAs can make a mess of businesses, the Masters and Doctors of Education sometimes get stuck in the wheel. They go faster and faster and they work harder and harder. But that won’t matter if they work on the wrong things.

Wishful thinking is killing us out here.

Shasta: What wishful thinking?

Mommy: If we just work harder or smarter, we can fix this mess. We can. But we can’t if we don’t touch the framework. We can’t get to Mars in one year. And we can’t fix a kid who has fallen four years behind in 180 days. Mars is just too far away.

Shasta: (Helpfully) Like your clothes.

Mommy: Exactly. And I could get those clothes. But I would have to be willing to invest hours of time and take engine-light-no-gas-gauge car across the wilds of I-5. Or I could even go to the mall. But I can’t fix my problem in the usual ways. The drawers are useless. I tried.

Here’s the key, Shasta: I tried once. I did a thorough search and unearthed one purple polo shirt. Now, if I’m smart, I quit here. I don’t go through the drawers again. After I have made a few circles in that wheel, I step out of the wheel if I’m a smart hamster and I am not running just for the fun of running.

Shasta: Running to run would be fine.

Mommy: Running for lots of reasons would be fine. But if I have a goal and I want to fix a problem, repeating the steps that did not work last time seems silly. Tweaking the steps seems silly. I could tweak my steps. I could look in drawers, on top shelves of closets, under dressers and under beds. Maybe I would magically find a pair of jeans. But how much effort would be required? How much would my odds of success go up? Life is a cost/benefit equation, Shasta. At a certain point, you give up and either go to Walmart or wait for your brother. Unless you want to breathe lungfuls of dust for no reason.

Shasta: The top of the closet might be fascinating.

Mommy: True that. How much naphthalene or paradichlorobenzene do we want to inhale, though? Mothballs and mice killers are strategically placed in this house. If the goal is useful clothing, I’m pretty sure I would have to wash anything I found.

Trying to get back on topic, Shasta, I think that’s part of the problem.

Shasta: (Doubtfully) Mothballs?

Mommy: Dumb plans. Plans that think about the end goal but don’t consider the costs. I think the problem may be inherent in government plans. Those guys never think about costs. They just assume someone will pony up the billions to make the changeover to the Common Core work. Chicago Public School administrators just assume the state will keep saying, “Sure, float another bond issue that’s bigger than the gross domestic product of some small countries.” Right now, they are trying to “fix” teachers as if that will somehow close the achievement gap. They would like the problem to be teachers because they can exert some control over teachers, much more than they can over students and student lives. But if teachers are only a small variable in this equation, fixing teachers will not change much, and maybe nothing consequential.

Shasta: Mommy, I am getting confused.

Mommy: I am so confused. No Child Left Behind seemed like a good idea. What I don’t understand, though, is why we keep doing things that don’t work. It’s time to get out from under the bed and out of the closet.

Shasta: (Firmly) Before the mothballs poison you. Not to mention the poor moths. Mommy, does anybody think about the poor moths?

Mommy: I don’t know. What they need to worry about is the bees, but that’s a whole different issue. Maybe it’s a perfect example, though. To kill the Zika virus, they sprayed poisons down from the air to kill the mosquitoes and instead killed the bees. We need bees to make flowers and fruits. For that matter, this plan that involves aerial spraying of toxic chemicals on pregnant women? A perfect example. Some people running the show seem to be in competition for the title, “Dumber than the dumbest rock on the planet.”

Shasta: Can rock intelligence be measured?

Mommy: (Sigh) Only by people who can speak Klingon telepathically, dear. So no. It’s hyperbole.

Shasta: (Doubtfully) I am not sure that makes sense.

Mommy: Shasta, stay on topic.

Shasta: I’m not the one talking about the Zika virus, mommy. Or telepathic rocks.

(Mommy laughs.)

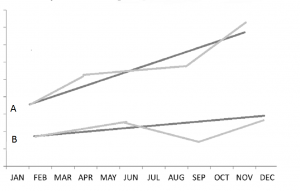

Mommy: O.K., Shasta, let’s see if we can put this in one-hundred words or less. We are treating differences of kind as if they were differences in degree. We are pretending that a child who enters a poor school district with 3,000 fewer words than a child in a wealthy district thirty miles away has not already lost the game. We are pretending that if both these children go to school for 7.5 hours daily for 180 days, somehow we can catch up the child who has fallen behind. But the research is clear. That knowledge and vocabulary gap will widen, not narrow. Let me show you a graph:

(Shasta stares at the graph, bobbing her snail head up and down.)

Shasta: On the left, that’s vocabulary words, right?

Mommy: Yes, I did not put in exact numbers. The idea is that Student A starts school ahead and is further ahead as the months go by. She can read more at the start so her reading goes faster at first and she adds new vocabulary faster. She begins with an edge. Also she loses less during the summer. The odds are good that she has more access to reading material over the summer.

Shasta: Sometimes that might not be true.

Mommy: True. This is a general idea. The research supports this idea. The kids who start two years behind often end high school four years behind. If they don’t drop out. In spite of No Child Left Behind, RtI, and other interventions. In spite of everything we are doing. I put in a steeper learning loss for Student B over the summer, because the research supports that, too. That’s the pale gray line on the bottom.

But the big question has to be – why aren’t the interventions working?

Shasta: (Curiously) Why? Why, mommy, why?

Mommy: Because Student A can already read A Wrinkle in Time in third grade while Student B is struggling with The Berenstain Bears’ New Baby. We want to think this represents a difference in degree. It doesn’t. This is a difference in kind, Shasta. Student B is so far behind that probably no intervention can fix the problem without a longer school year and a longer school day. Oh, a brilliant teacher might be able to get Student B back in the game. But brilliant teachers are thin on the ground. We have been trying to figure out how to make them for years and we still can’t do it. We can make better, more effective teachers. But I don’t think brilliance can be taught, not the kind of brilliance that can teach Student B seventeen new words each school day, which is what some of our kids would need to learn to catch up. Three-thousand divided by 180 equals 16.66 words – and keep in mind that while our kid who is 3000 words behind is trying to catch up, her target is moving. Her target is reading A Wrinkle in Time and adding new words to an already much larger vocabulary every single day. So the real number needed to catch up may be 20 new words per day or more.

Shasta: Wow.

Mommy: Yes, wow. More people need to do the math. More people need to look at the math. No best practice can fix this. No “working smarter” can fix this.

Working smarter could help. We might try shaping our whole curriculum along language-learning lines, for example, along with necessary math skills. We might jettison inessential activities. But the truth is many academically-challenged schools are already going that direction. They still don’t get those lines to converge. And I end up feeling sorry for their students who seem to have a lot less fun than kids in higher-scoring, wealthier districts. Those higher-scoring kids who entered school ready to read? They take mornings off to watch scientists freeze balloons and authors explain how they wrote their latest kids’ favorite. My last, formal year, my school allowed ZERO field trips until after the spring state test. The wealthy suburbs around us were all going to zoos, museums and nature preserves. The private school that asked me to sub was building actual structures on the ground to teach math concepts. We did math/English/math/English/math/English until the kids were choking on that stuff.

Shasta: But they have to do the math and English to catch up, right?

Mommy: They do, and we cannot make the whole world fair and fun. But I think we need to face up to an important truth. That 180-day school year has to go in some districts. Those seven-hour days need to go. If we can’t get the results we need within those time constraints, the time constraints need to be changed. Not for everybody. That 180 day year worked great for my own girls. But kids who have fallen behind should be given a real, realistic chance to catch up. That means more time in school. Period.

Shasta: Wow, telepathic rocks. Do you talk to rocks, mommy?

Mommy: (Sigh) If I had spent much longer in public schools, Shasta, I might have.

Shasta, you remind me of a favorite student. I was on a math roll, proud of how attentive my students were as I explained a new concept. One boy raised his hand and I felt elated that I had stimulated his curiosity. Then he asked me the age of the oldest tree in the world.

Shasta: Is it old?

Mommy: Around 9,500 years. I looked it up. Look up the tree Methuselah. I think Methuselah might be the second oldest known tree. Methuselah’s around 5,000 years old.

(Mommy smiles at Shasta.)

I loved teaching, but it can be a little hard on the pride some days. Seemingly foolproof lesson plans fall flat and other less-inspired plans take off like rockets. But I have figured out one thing. If we are ever to catch our tree-thinkers up, we can’t send them home for more than half the year. That longer school year has to be Part One of any fix-it plan.

Shasta: What’s Part Two?

Mommy: We have to stop boring the crap out of them.