(A post for newbies and others.)

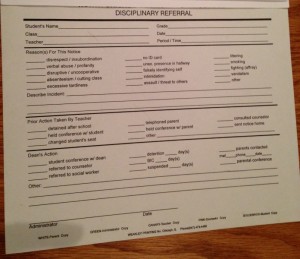

The above disciplinary referral form is fairly typical. I stumbled on some numbers from a meeting I attended. These numbers come from a middle-class high school where I taught Spanish. Toward the end of the school year, out of 2084 students, 1,354 had no disciplinary referrals, 322 kids had one referral, 283 kids had 2-5 referrals, 66 kids had 6-8 referrals and 59 kids had 9+ referrals.

In and of themselves, the numbers don’t tell us very much. The referral paper trail depends upon a culture. In a school where referrals result in action, many more referrals may be written, especially when that action is timely. If two weeks normally elapse before any detention or consequence happens, referrals will fall, as teachers opt for immediate, in-class consequences. In a school that requires a great deal of teacher intervention before referrals can be written, fewer referrals will make their way to the Dean’s office. Once a teacher has called parents and held a conference with the student, any extra paperwork may seem like an unnecessary burden given the expected payback from that work. If referrals fall into a black-hole and nothing happens without direct teacher interaction with administration, very few referrals will ever be written. Why bother? I have worked under all these conditions.

Middle schools and high schools may go through thousands of referrals. More than a few times, I have ended up photocopying the front sheet of a referral form while my school waited for new forms to arrive. On top of habitually running out of paper for the copy machines, my last school seemed to have regular referral-form crises.

I’d like to focus on only a few numbers above, though, the 66 kids who earned 6-8 referrals and the 59 kids who earned 9+ referrals. Those numbers ought to give many people pause. Together, these two categories contain 5.9% of the high school’s total population. That’s slightly over 1 in 20 kids. They reflect a daunting and underdiscussed problem within America’s educational system.

Referrals are only written for a fraction of misbehaviors, and I’d say many or most teachers only write up fairly serious misbehaviors. A few teachers burn through referral forms like locusts in a wheat field, but most teachers would rather manage minor infractions themselves. Again, numbers vary by school culture, but experienced teachers often prefer to deal with minor misbehaviors directly, rather than wait for later consequences from an office. If Aaron calls Mark a “shithead” without rancor or any attempt to offend, as a random word choice in a regular conversation, I don’t want to lock into an elaborate disciplinary process. Referrals take time. I don’t want to let the incident go, of course. But making Aaron miss five to ten minutes of lunch while I discuss proper language will often solve my problem. New teachers and teachers under scrutiny may also avoid writing referrals for fear of appearing unable to manage their classes.

That one in twenty kids thus comprise only a fraction of the disciplinary issues teachers encounter during the year, possibly a small fraction. The actual fraction will vary depending on administrative response time and helpfulness. During the year of the black hole, clumps of hair could be seen in the hallway and I am not sure that all those fights were even written up.

Here’s the academic whammy that we too seldom talk about. If 1 in 20 students are getting 6 or more referrals in a year, and about half of those students are getting nine or more referrals that year, actionable misbehavior has become a regular part of classroom life. A teacher with a homeroom of 30 students may easily get two to three regular offenders in that class. In a very unlucky draw, four or more Dean’s office regulars can be placed in the same room.

Eduhonesty: I plan to continue this thread in another post, but I’d like to make a few observations for new teachers to end this post. If you are like many new teachers, you may be starting in an economically or financially-disadvantaged district. These districts tend to have greater disciplinary issues, often spawning many more referrals than academically and financially stronger districts. Unsurprisingly, they also have disproportionately more teaching vacancies. Major urban areas always have openings. Government numbers show that larger schools in urban areas are particularly prone to one category in the statistics: Widespread disorder in classrooms. Larger minority populations and higher poverty rates also tend to be correlated with higher widespread disorder. More information is available at the following site: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/crimeindicators/crimeindicators2011/tables/table_07_1.asp.

If disciplinary issues are causing you stress and confusion, please ask colleagues for advice. They have been there. Strict routines help. Clearly defined rules and procedures help. Carefully arranged seating charts help. If the chart is not working, feel free to alter seating arrangements, but you want to avoid making frequent changes. You are striving to create a safe, stable atmosphere.

Ask colleagues about writing referrals. Does this offense merit a referral? How many referrals are too many? Which dean or administrator is most likely to help? What should you do if the referral does not help? How can you write that referral without losing class time? When do you call security? What do you do in a fight? What does the school consider to be excessive tardiness? How disruptive must student behavior be to qualify for a referral? How profane? You need to learn your school’s culture so you don’t seem petty and nitpicky or the opposite, too lenient with disciplinary infractions.

I’m going to give a piece of advice here. Don’t touch anyone in a fight. Aside from the question of getting yourself injured, I saw a colleague sacrifice his job with this move once. The student’s mom complained that my colleague had pulled her son off another student too roughly. One month’s suspension, half of it without pay, and my colleague ended up in a downward spiral with the district. He’s happily teaching in another state now, but once you touch a student, you can end up in a parent’s crosshairs. Don’t be certain that the administration will back you up, especially if you are a new teacher. If the fight starts, call or yell for security immediately while you move students out of the way.

A second piece of advice: If you have a class that has three or more students who are regularly disrupting the class, talk to administration about rearranging student schedules. You will have to do this soon. The later in the semester, the less likely you are to succeed. If you can split your four into two and two, daily life will improve dramatically. You can’t always do this — some schools will not touch established schedules — but when enough learning time is being lost or commandeered by out-of-control adolescents, a desperate roll of the dice to try to separate students can’t hurt. I’d be ready with specific instances where the dynamic between troublemakers has made learning problematic for the rest of the class.

For those new teachers starting in academically- and financially stronger districts, I’ll pass on the same advice but you may be lucky enough to confront these issues far less often. The desire to go to college helps keep students out of the Dean’s office. As free or reduced lunches fall in the government table referenced above, so does widespread disorder in classrooms.

That’s the academic whammy that does not receive enough attention. The teacher who deals with disciplinary issues regularly starts at a disadvantage in terms of academics and test scores. Disciplinary infractions and referrals suck time out of the school day. They take up afterschool time as teachers call home, hold conferences, stay behind for detentions, write up notices, consult social workers and counselors, rearrange seating charts, etc. Most importantly, behaviors that lead to referrals regularly distract classes. In this time when merit pay, evaluation numbers and even retention may hinge on student performance, teachers in financially- and academically disadvantaged districts end up at a disadvantage outside of their control.

I’m sorry to say that my last piece of advice proceeds naturally enough from what I just wrote: Are you working in that large, urban school? Are your students test scores and behavior being used to assess your performance? You ought to try to get out. Come spring, you should explore online postings for new positions. Yes, maybe you love your school. But your odds of succeeding as a teacher will go up as you move up the socioeconomic and academic ladder. When student test scores, behavior and enthusiasm become the major criteria in any teacher’s evaluation, that teacher’s best move will be to strike out to find a district where both test scores and student aspirations run high.