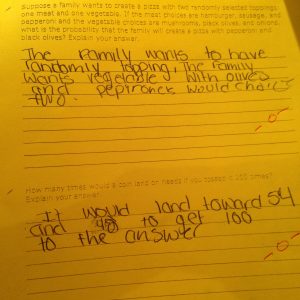

Our students are not data. They are children. But educational reformers, state department of education employees, and school district leaders sometimes seem to have forgotten this truth. I spent over 20% of my last teaching year giving mandated tests and quizzes to my math classes, in many cases tests my students could not even read, written by an East Coast consulting firm based on Common Core standards that were four years above the test-documented academic levels of two of my classes. I also gave extra tests and quizzes because my school’s administration had decided grades were to be based entirely on tests and quizzes. The only way to save my students grades became extra tests and quizzes designed to raise their averages.

What did that year of fail, fail, fail, retake, retake, retake accomplish? Not nearly as much as rational expectations combined with desperately needed remediation might have accomplished. But when I stepped off the common lesson plan to remediate, I risked being threatened by my administration if caught. The threats went as high as termination. “Do it or else!” was the mantra of the new Principal (or hired gun) brought in from another state. The Assistant Principal punctuated that mantra with his own, “No excuses!”

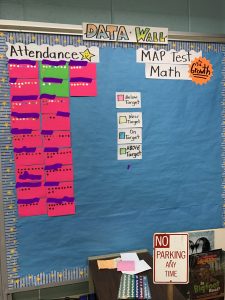

My district had to show the State of Illinois that school data was improving. The consensus seemed to be that only by teaching 7th grade Common Core standards could we improve the data — except often those standards were unteachable. My two bilingual math classes both entered my class at an average 3rd-grade-level in mathematics according to their MAP™ benchmark test scores.* English language learning scores came in at comparable levels. No child can leap four years in a single bound.

I persevered. I wanted to keep my job. After awhile, I changed my mind. Nobody in their right mind would want that job, the one where a teacher keeps giving kids impossible work, while under regular threat, and then tries nonstop to repair all the damage she knows she is doing by following scary orders. I finished out the year for the kids, carrying an emergency resignation letter in my glovebox for most of the winter.

Eduhonesty: I’m retired. The damage has been done. I’d like to share a few questions that I think require answers, however:

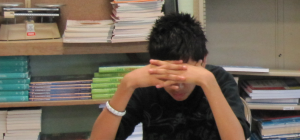

In the name of data, how many impossible tests did we make “Isidro” take throughout that year? How many Isidros are taking similar tests this year? If Isidro bombs six math benchmark tests, as well as corporately-designed evaluative unit tests, and his big state test, will teachers conclude Isidro must be mathematically challenged? Will Isidro’s test results prejudice future teachers? Expectations can become self-fulfilling prophecies.

Most importantly, how will all those incomprehensible tests influence Isidro’s view of himself? Even if Isidro’s teachers manage to keep open minds, will Isidro?

*Nonteacher readers — Benchmark tests are given at designated times throughout a school year to measure students’ ongoing academic progress, especially in English and mathematics.