We tend to overvalue the things we can measure and undervalue the things we cannot. ~ John Hayes

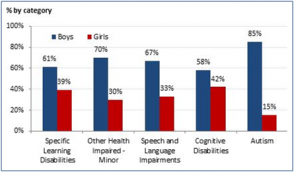

(How much does the above graph tell us about boys and girls? Maybe a great deal. But this graph may also express researcher or teacher bias. I’ll go out on a teacherly limb here and observe that girls tend to be quieter and less troublesome in class on the whole, and therefore are less often referred for testing.)

(How much does the above graph tell us about boys and girls? Maybe a great deal. But this graph may also express researcher or teacher bias. I’ll go out on a teacherly limb here and observe that girls tend to be quieter and less troublesome in class on the whole, and therefore are less often referred for testing.)

“The government are very keen on amassing statistics. They collect them, add them, raise them to the nth power, take the cube root and prepare wonderful diagrams. But you must never forget that every one of these figures comes in the first instance from the village watchman, who just puts down what he damn pleases.” ― Josiah Stamp

In the book Big Data, authors Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Kenneth Cukier discuss former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. They describe how McNamara tracked U.S. military success during the VietNam War by using body count data as the basis for strategic plans and recommendations. Yet generals subsequently suggested those counts had been questionable measures of progress and unreliable to boot. In particular, counts had been exaggerated,(Page 165 – 166) a completely unsurprising result when higher body counts become the yardstick that measures an officer’s success, especially given that those counts will almost always be impossible to check. The bodies don’t wait for a recount.

Garbage in, garbage out (GIGO) appears to have applied to many of those body counts, but the counts kept coming. The counts kept being published. The counts kept being used to plan U.S. policy. Enamored of data, American government and military leaders made decisions using numbers whose quality and usefulness frequently remained unchecked, as well as misunderstood.

Mayer-Schönberger and Cukier observe that data can easily delude decision makers, including educational data derived from standardized tests. We don’t know when or if the tests capture the abilities of school children, especially when a test has been set too far above or below actual student learning levels. Do standardized tests capture the quality of teaching? We cannot answer this question. Many factors enter the educational equation, and the best teaching in the world may not be able the fix the damage done by moving into three different districts during the school year and missing most of a month in school during the process. Teaching cannot “cure” autism, dyslexia or traumatic brain damage. Teaching cannot compensate for an inability to read the test itself, a fact of life for many students even when their reading skills improve by documented years of “standards” over the course of a school year. Even in cases where a standardized test represents a reasonable set of questions for the population being tested, we do not know to what extent relentless test preparation versus a a broader approach to a more classical education may be affecting comparisons between districts. And then we should factor in cheating, a topic that has hit the radar many times in the last few decades. As the testing stakes got higher, I’d guess cheating increased. Why would anyone expect otherwise?

My journals and phone notes are filled with self-exhortations to fix data walls, update data walls, and add new data walls, preferably walls with pictures. Journals tell me to prepare more batches of data in cyberform for review by coaches, colleagues, administrators or random Grand Poobahs from the State of Illinois. I carried those journals to meetings for years. District laptops were district property, a twisted mess of shared documents, so I preferred my neatly lined books and private thoughts. As I reread journals, I am amused and bemused by the data..data..data..data chug-chug train that steams through their pages.

Education has embraced data-based teaching and learning. If all the data spreadsheets from 2016 were printed and stacked in one place, I would not be surprised if that stack reached the moon. The stack would exit the Earth’s atmosphere I am sure. If all the useful, true data were stacked, however, the useful, true stack might barely clear the Empire State Building.

Readers are no doubt thinking, “She can’t know that!” No, I can’t. But that does not mean I am wrong. It simply means my proposition remains unprovable. We don’t have the time, money or statisticians necessary to check my (alternate?) facts. I suspect we would bog down first at the word “useful.” If data in a cumulative folder duplicates our latest data and leads to identical conclusions, is the new data useful? If teacher observations, grades and quizzes could produce an identical conclusion with less time loss and money spent, is the new data useful? Is the new data HARMFUL? If the minutes spent gathering that data were essentially duplicative, sucking time away from student instruction, have we created a net loss of learning, rather than a gain?

Data has a purpose. That’s our big problem. Humans in pursuit of purposes will find ingenious methods to reach their goals, and not all these methods will be ethical or honest. Not all these methods will consider ancillary damage from data-gathering efforts. If ancillary damage – such as loss of hope and resilience in students unable to make irrational targets – cannot be measured, that damage may conveniently be ignored, or lightly addressed in cheery posters buried among data walls and copies of Common Core-based standards in the classroom. We have begun working on “mindset” in the last few years, but we seldom address the question of whether our focus on data helped form, or even built, the bleak mindset we are working to overcome.

When my principal gave two benchmark tests, MAPTM and AIMSwebTM fall, winter and spring during my final, official year teaching, she was gathering data for the State of Illinois, and she wanted the best data she could get. From a tactical standpoint, her move made complete sense. In terms of lost classroom instruction hours, I viewed those lost hours as an appalling waste of my students’ time. As teacher-readers know, the school has cumulative folders filled with test results from previous years. Throughout the year, teachers are gathering information as they give subject-specific tests and quizzes. A perfectionistic administrator in a threatening environment will gather data with the intent of cherry-picking the best results. Her job depends on her numbers. But classroom hours slipped away as data demands triumphed over sound pedagogical practice.

In the end, we may simply show that, yes, we have no bananas, and for damn sure we can’t do this math any better than the math we had last week. GIGO. But GIGO does not come without a cost. One opportunity cost of state-required data-gathering efforts will be all the useful remedial instruction that never takes place while we are gathering data. If the common lesson plan ends up based on the math expected to be on the state test, rather than math students have learned previously, that lesson plan may have close to zero to do with what my students need to learn to succeed in mathematics.

My Principal took her own approach to the data problem by giving six benchmark tests. She got her data, too. She could show the state we were rapidly improving. Were students actually learning more quickly than in previous years? Were they learning more or even as much as they might have learned without our barrage of testing? No one will ever know. Like my hypothetical stacks of spreadsheets, we don’t have the money or manpower to evaluate that year’s efforts. We have a bunch of tests and spreadsheets, but the students have moved on, the Principal has left the district, and I am going to meet three former coworkers who left the district with me for lunch next week. These are just the friends I kept. Walking the halls of my old school when I sub there, I see almost no one I know.

GIGO. The whole approach to data that year sucked up class after class, producing a crazy quilt of often superfluous numbers. By October, I already had written the resignation/retirement letter I kept in my glovebox. People tend to abandon the ship after producing spreadsheet after spreadsheet that may mean little or nothing. So many of those spreadsheets merely documented what we already knew, or should have known.

GIGO. Failures were documented in red on many of our spreadsheets, failures that fell on the shoulders of those teaching special education or bilingual classes especially. I’d call that red appropriate. In those classes in particular, students and teachers bled data until some of us just expired.