Again, I will rephrase a central question that has been posed before by this blog:

How many children and adolescents are resilient enough not to let regular, low test scores affect their view of their potential? This question shouts at teachers giving standardized test after standardized test, but I hear its whispers echoing as we adopt Common Core Standards. I return to those tests I was required to give my students, tests based on standards sometimes more than four years above their documented academic levels of achievement when they first entered my classroom.

One problem with assessing damages from irrational testing rests in the difficulty in measuring human resilience. For some students, those failed tests might as well be water off the duck’s back. The degree to which a kid feels sad or defeated by events varies from day to day and kid to kid. In Myers-Briggs terms, some kids are thinkers, some are feelers and a percentage hover in the middle. Some go down obediently. Some fight back against the injustice of our inappropriate tests and standards. Some judge themselves wanting, while others perceive they are playing a loaded game. Some do whatever they feel like at the moment. If classrooms had chandeliers, a tiny but persistent group of high-energy boys or girls would have to swing on those chandeliers for the pure fun of it, especially on test days.

Current wisdom wants us to believe that resilience can be cultivated through adoption of positive-feedback loops, and I believe that concept stands up to scrutiny – to a degree. The girl who gives herself positive self-messages has a better chance of standing up to today’s testing onslaught than her more pessimistic counterparts. “I will study harder and I will do better on the next quiz” certainly beats “I hate this class and I can’t do math.”

But like autism, resilience and its cousin optimism tend to fall along a spectrum. Some people see that glass as half full, others see it as half empty and a few even see the glass as a dangerous, breakable object that may shatter into sharp shards at any moment. Maybe optimism stems from higher serotonin levels, maybe from familial support and trained coping strategies, and likely often both, but resilience and optimism are not distributed equally.

I helped in a public preschool last year, working with a group of three-year-old children who were mostly nonverbal or barely verbal. They tended to have supportive parents, a reason they were receiving special services from their school district so quickly. Some were laughers, some were criers, and some were prone to tantrums. Laughers sometimes cried and might also have tantrums, but we knew our criers. I can name them still. I can name the kids who would be excited by a new challenge. I can name a few kids who always said, “Help!” and looked anxious when asked to try something new. If the Principal had asked me to list anxious kids, I could have written out that list. My list might not have been perfect – some kids mask anxiety well and others whine so much they may seem more anxious than they feel – but that list would be a good start. By three-years-of-age, some children react to pressure with fear, and pressure can be as simple as being expected to wash your hands, find the symbol that represents the first letter of your name, and then write your name.

One child’s fun challenge is another child’s “Oh, no!”

I’m drifting a bit as I emphasize the individual differences between America’s students, but I am also becoming progressively more concerned as we attempt to cultivate resilience in our students. Yes, mindset matters. Yes, resilient students do better in school. But I wonder how often we are emphasizing resilience now because we have created a toxic learning climate that is stripping away some or even many students’ self-esteem.

One reason I knew the time had come to retire from teaching: I’d reached the point where I no longer felt like bringing down the hammer on my cheaters. When administration required that I give impossible tests to my students, tests set sometimes a full six years above their documented, functioning, academic level, I had a hard time getting excited about cheating. If I had to play a game I could never win, no matter how hard I tried, I might have cheated too.

I reflect on my last formal group of students sometimes. A few students succeeded under the Common Core No Excuses regime of that year — the academically strongest kids and a few others with exceptional drive and willingness to seek help. But almost everybody else got walloped. I worked relentlessly to keep them in the game, to salvage their hope. Sometimes I bought them Saturday morning McDonald’s treats just to get them to stay in the game.

But every single child in the world is unique. In a fight on the playground, some fold into a fetal position, some come out swinging, some run away, some call for the teacher, and some keep pounding away even after they realize they have lost, and the blood from their nose starts choking them. Some fight fair. Some pull out hair, clumps that blow through the hallway later. (Clearly, I have seen too many fights.)

I expect the Common Core Standards to fail America’s students because those standards have been designed to be One-Size-Fits-All. One size never fits all. The petite women of my acquaintance almost all look silly in serapes hanging down to their calves and ankles.

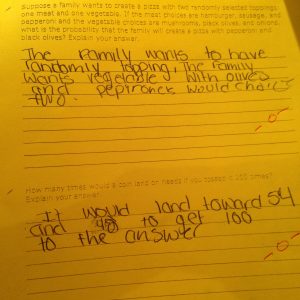

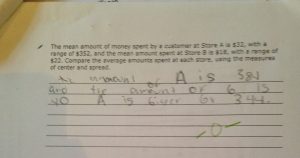

My last official teaching year felt unreal at times, as administrators kept demanding I give tests and quizzes my students could barely read. To illustrate, I’ll offer another copy of a 7th grade Common Core unit test given to a bilingual student. The special education teacher had to give identical tests and quizzes to her cognitively delayed students, too, and those students’ tests resemble the test below.

This is what happens when a 7th grade Common Core Unit Test hits a student operating at a 2nd grade level in English and a 3rd grade level in mathematics up the side of the head. I could pepper this chapter with similar efforts. This is what happens when a student’s academic level differs sharply from a required standard. Raising the standard for this student, absent a tremendous amount of remedial tutoring, will only produce a sillier set of answers, too.

Let’s forget all the details above, though, and ask the one question that matters most: How did this student feel at test’s end?