BY SEAN ROBINSON

srobinson@thenewstribune.com

Editor’s note: Compiled from reports to Tacoma police. Taken from the Tacoma News Tribune police beat article.

Nov. 9: Spatters of blood covered the principal’s shirt and shoes.

The school resource officer at Oakland Alternative School, answering a panicked radio call, asked what was going on. The principal said he’d just broken up a fight between two students. One had a bloody nose.

The principal said he noticed the two students confronting each other outside and ordered them into the main office. As they walked in, the fight started. One boy, 17, took another boy, 16, to the ground and started throwing punches.

The principal pulled the attacking boy away and stowed the boys in separate rooms.

The officer spoke to the younger, bloody-nosed boy first. The boy didn’t want to say anything at first.

He said he wasn’t a gangster, but his friends were, and so was the older boy. He said the older boy came at him, started talking trash, tried to pick a fight and sucker-punched him.

HE SAID HE WASN’T A GANGSTER, BUT HIS FRIENDS WERE, AND SO WAS THE OLDER BOY. HE SAID THE OLDER BOY CAME AT HIM, STARTED TALKING TRASH, TRIED TO PICK A FIGHT AND SUCKER-PUNCHED HIM.

The boy wouldn’t say anything else. He wouldn’t say what the trash talk was about.

The officer spoke to the other boy, who said even less.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” the boy said.

The officer relayed the story he’d heard. Was that true?

“I don’t know,” the boy said.

Did he throw the first punch?

“Yep.”

The officer told the boy he was under arrest for misdemeanor assault. The boy stayed calm.

The officer spoke to the boy’s mother. She said her son had said a rival gang was after him, believing he was the gunman in a recent shooting in Tacoma’s Salishan area. The mother believed that was the basis for the fight at the school.

The officer booked the boy into Remann Hall, adding a charge of marijuana possession after staffers found a packet of pot in the boy’s shoe.

Read more here: http://www.thenewstribune.com/news/local/crime/article44918637.html#storylink=cpy

A perusal of the same newspaper has other articles about schools. In one, we are told that police are looking for a Foss High School student who apparently pointed a gun at another student on Monday. It’s not clear exactly where the incident happened, but the school went into lockdown.

Eduhonesty: I taught in an alternative high school some years ago. I remember the police dogs coming in. I remember students discussing eating their marijuana. In a pinch, humans can eat dried grass, no problem. This article has so much content that needs exploring but I think I’ll stick with one aspect of the academic crisis referred to in this article, the crisis of gangs and violence in our schools in a time when teacher evaluations are heavily based on student behavior. In particular, I fear a brain-drain that I am watching from the sidelines.

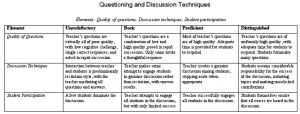

Teacher evaluations based on a common rubric like the sample above are inherently unfair. That sample is only a small part of a large rubric that can result in a more than twenty-page evaluation. I have one somewhere. The standard evaluation in Illinois has become huge, so huge that at times its accuracy must be suspect. In an hour, no administrator can observe all 20-some pages worth of behaviors. Admin can put “not observed” but I know that some administrators are “inferring” as they decide to score categories they have not specifically observed.

How does the rubric work? In a system commonly used by districts, a teacher would receive 1 – 4 points in each category in an evaluation, so my snippet above would be worth from 3 – 12 points depending on an observers view of behaviors in the classroom.

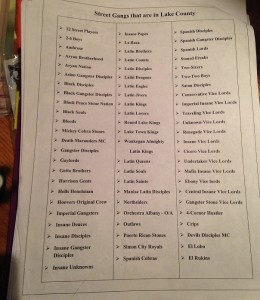

Administrators in alternative schools understand an alternative high school is a different animal, so I am not concerned about that alternative school as much as I am concerned about teachers in “feeder” schools. Some schools supply a higher percentage of students expelled for weapons, drugs and other offenses. Some schools contain many more gang members than others, gang members regularly attending classes where they are setting up the marijuana etc. sales that supply the gang with revenue. When expectations for teachers in those schools are the same as they are for teachers in middle class schools with limited or no gang activity, teachers in gang-infested schools end up being trapped and potentially set up to fail.

I’d like to ask readers to pause to consider how heavily the category of student participation might be affected by numbers of gang members in a classroom. Then think about how much better participation might be (on average) in a classroom filled with college-bound students.

In earlier times, when teachers were assessed based on their own efforts and performance, with an understanding of urban challenges, the system worked. Now, student behavior and class performance have become a heavy component of many evaluations and teachers are at a disadvantage when they choose to work in urban or disadvantaged areas. Teachers lose points for student misbehavior or off-task behavior, reducing evaluation scores. How might a teacher manage that problem of detached students? The problem of students who have gone to school mostly to sell drugs?

Here’s my take: If I had started working in these times, I’d have moved out of disadvantaged schools almost immediately and never gone back. When student behavior determines a large percentage of an overall evaluation, the best tactical move is to seek a school with students who intend to go on for further education, a school usually found higher up the socioeconomic ladder. Those schools pay better and now they frequently result in higher evaluations, since college-bound students are more likely to demonstrate the behaviors that give high points on the teacher evaluations.

The category “student participation” only forms part of the picture. Student interest and participation will also affect questions formed and asked. “Discussion techniques” and “quality of questions” will also be affected by class composition. If I have a class that is academically very low, I have to ask simpler questions more often. If nothing else, I will be asking these questions to prime the questioning pump, to get students to begin to answer questions so that I can go on to harder questions once the discussion develops momentum. In a stronger class, I might be able to leap straight into the deep, critical thinking questions, but I know from experience that providing academically-lower classes with a few “wins” before I move into the tougher questions works better than a nonstop stream of complex demands. I risk losing evaluation points now if I start with those simpler questions, though.

I understand the rationale for including student responses in evaluation rubrics. Still, when student responses become a heavy determinant in evaluations, the smart move has to be leaving our academically-weakest schools. The high schools where I live send more than 90% of their students to college. Those classes will contain higher levels of academic motivation overall than classes in gang-heavy neighborhoods where student preoccupations with safety and survival, not to mention drug revenues, may sometimes trump academics.

What’s the effect of student-based performance evaluations on staffing? I talked to a former colleague a few weeks ago.

“Oh, (my still withheld name!),” she said, “they are all new. All of the old teachers are gone. It is lonely.”

My colleague is putting in one more year before she retires. Many colleagues shifted to other teaching jobs last year. They moved socioeconomically up when they could and, if not, to higher paying districts. A number retired earlier than they had intended.

The young, smiling faces in my old school seem quite likable. I went to visit a few weeks ago. But I talked to a younger colleague who mentioned the existence of a problem they keep running into now at the school. An enormous amount of specific knowledge has walked out the door. The people who know the details of giving certain tests and managing certain procedures? In some cases, most or even all of them have left.

When my colleague above finishes her last, lonely year and retires, she will take with her an in-depth understanding of the science standards, equipment, and procedures that no one else possesses. She has also run a horticulture project almost entirely on her own, finding the materials — often paying for them herself — and teaching students how to raise vegetables and household plants. During holiday seasons, students sold what they grew, subsidizing new materials purchases. That project is only peripherally in the curriculum. Many students loved growing flowers and vegetables, but when my friend leaves, those florae are likely to become part of the past. Who will step up for all the unpaid, time-consuming work that project requires? My colleague’s extra work might be worth a couple of “professional responsibility” points on the twenty-page evaluation, but it’s basically a labor of love by a woman who loves to teach and never expected to be rewarded.

My colleague might have stayed longer in a more-supportive environment, an environment that did not include an evaluation system that many older teachers regard as a “gotcha” of sorts. They remember when the feedback they received felt mostly appreciative and positive. Now, they receive page after page of well-meaning suggestions for improvement. Even when a teacher gets a “3,” meaning he or she is proficient, suggestions for improvement may be included in final paperwork.

The rubric referred to above is not national, but affects millions of teachers. Other states have other rubrics. The larger problem lies in the fact that evaluations are now being used primarily as teacher-improvement tools. I suggest that we decouple evaluations and improvement – creating two separate systems, one to be used to improve pedagogy and one to evaluate teachers. Otherwise, smart teachers will head to districts that will provide them with more positive feedback — districts with stronger student participation and more motivated student behavior.

Or they will just quit.