I have hammered the theme of opportunity costs incurred from excess testing in earlier posts. The SLO provides a great example. SLO (Student Learning Objective) is another government-mandated test, a content-specific exam aligned to curricular standards.

As part of the SLO process, I was obliged to give all my classes tests which covered the material we planned to teach this semester. Most of the material on the SLO test had not yet been taught. I reassured students repeatedly that their first SLO tests would not be part of their grades. I recommended they try to remember questions when possible, since the tests would be repeated as major exams at a later date. I reiterated that I was not going to hold them responsible for not knowing vocabulary and concepts they had never seen before. Readers need to be clear that students are not expected to know the material on the first SLO test. We are handing kids tests filled with questions on content they have never seen.

The purpose of the SLO is to evaluate teachers, not students. The rationale seems to be that the better students do on the second go-round of the test, the better the teacher must be. I’d like to observe that this will only be true for age and learning-appropriate tests. If I test a sixth-grader on high school physics, both the first and last test can be expected to be epic fails, even in the hands of the best teachers. Under Common Core, the bar has been raised to levels that can defeat many diligent students, but that’s another post. I want to stick with the SLO.

The first part of the SLO was not particularly time-consuming, one day lost to exams that would not be included in grades. Since all classes will give SLOs, a whole day of instruction is actually lost with that first test. Teachers must also grade their SLOs, losing class preparation time and the opportunity to grade “real” papers.

After the second administration of the SLO test, the time suck really begins. Teachers are expected to assess learning progress between test one and test two. This progress will be factored into their final evaluations. I confess I have not done my SLO. I am hoping administrative poobahs will ignore my breach of state requirements — SLOs came out of a state law — since I am retiring. If not, I have all the tests. I have always kept my tests in case questions arose later. This year, I have been obliged to save so many tests that I think the contents of my drawers would keep that library in “The Day after Tomorrow” warm for the afternoon or maybe even the whole day.

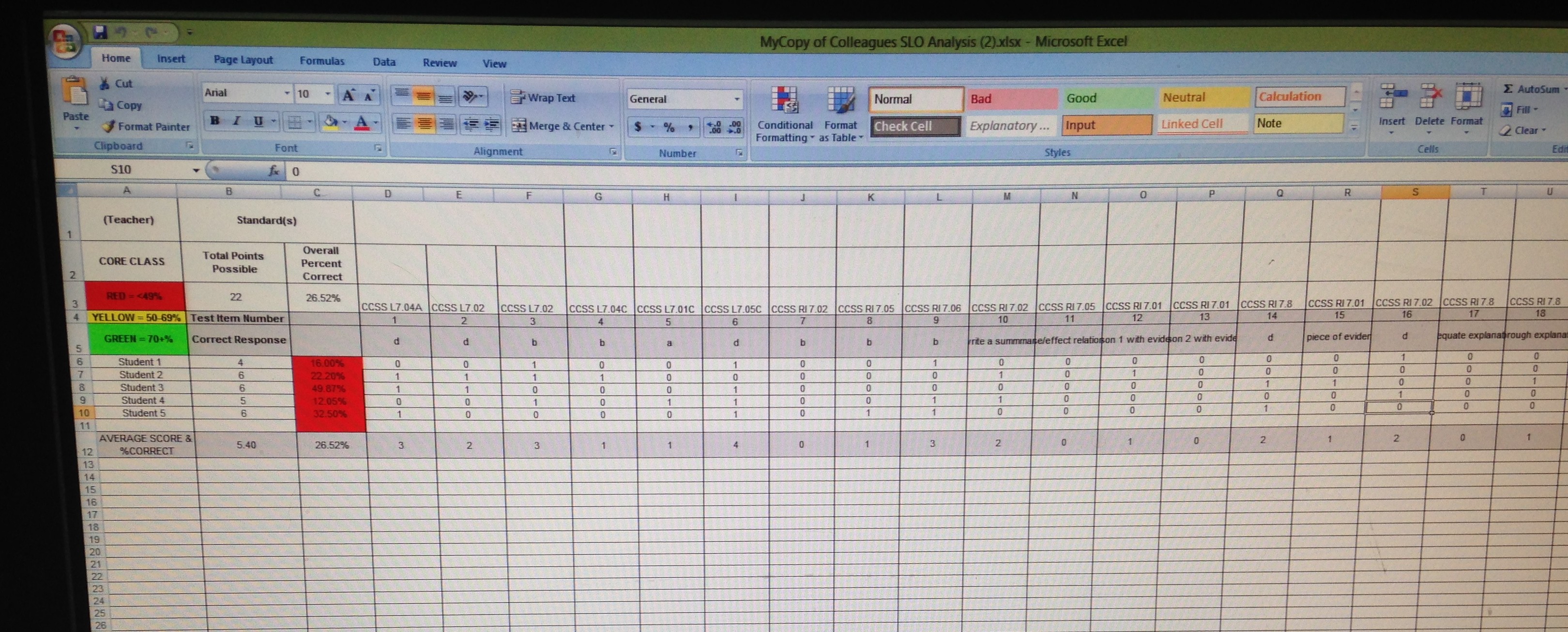

A picture will help make the time loss in this process easier to understand:

This is a sample of the template used by one department. The CCSS are Common Core State Standards. Each question has to be recorded according to what state standard(s) apply. Success on each question has to be assessed. My sample has five students but some classes will have around 30 students. Standards and scores must be assessed. Scores must be color coded. If you are special education or bilingual, you can expect to see red all over your spreadsheet. That sheet will be dripping the blood of your falling evaluation.

This is the work I have not done, the work I hope never to do. This spreadsheet represents at least a full day of my time and probably then some. I am not a fast grader, as I have previously noted, and then I would be expected to catalog all this work after I am done. Teachers are going to have to conference with a coach when they are done. The coach means well and I cannot fault the district for helping teachers learn to navigate the SLOs. But that’s more time lost. Avoiding the SLO alone provides me with adequate reason to consider retiring. As I sit here, I am imagining what teachers must feel like as they look at the red sprawling across their spreadsheets, knowing that red will affect their evaluation, possibly even lead to their failure to be recalled for the next year.

Doing this spreadsheet seems a bit like being forced to carry your own cross.

Eduhonesty: Of course, some results will be fine. I narrowly avoided a SLO last year that would have been heavily in my favor, I believe. As part of my teaching assignment for a half-year when I was at the high school, I was given a Consumer Math class that included almost all juniors and seniors who were college-bound. For SLOs, this was a dream combination. Students knew very little of the course content, since this was an elective that was not part of the core curriculum, and they were motivated to get good grades for college purposes. When I transferred to the middle school, I happily abandoned that SLO but maybe I ought to have done all the work since I knew that final showed tremendous improvement over the semester since the first SLO. I’ll confess I was just glad to avoid making my spreadsheet. I am sick of extra work.

That Consumer Math class highlights one major problem with the SLOs, though. Luck of the class figures hugely in SLO results. Special education teachers can be at a tremendous disadvantage, especially in a district that is forcing them to give the same regular instruction and tests as “regular” teachers. AP or gifted teachers, on the other hand, are likely to go into the SLOs with a winning hand, especially if they are teaching a subject like Consumer Math, one with relatively easy content that students have not encountered previously.

Another problem with SLOs can be seen in my snippet of a spreadsheet above. How many lessons could be planned in the time that one SLO spreadsheet demands, especially if 29 students must be individually recorded on separate lines with all the accompanying common core standard columns? How much tutoring could be done? Does the SLO make the teacher evaluation process more efficient in any way whatsoever? The state is already using the 4 domains, 22 components, and 76 elements of the Danielson Rubric to evaluate teachers, a cumbersome instrument that the Danielson group has already attempted to condense into “clusters.” My last evaluation was 22 pages long without any SLO data added.

The opportunity cost resulting from the increased evaluation demands and SLOs strikes me as nothing short of absurd. Is there any evidence that this new system works better than the two or three page evaluations from the past?