My post’s title ought to be “Reining in the tests” or something like that, but who wants to read about more tests? Like death, taxes, politics and other forever-topics that somehow never seem to come out right, testing has become a quiet thrum in the background of daily life, one that sounds faintly unpleasant and spurs a desire for distraction.

My post’s title ought to be “Reining in the tests” or something like that, but who wants to read about more tests? Like death, taxes, politics and other forever-topics that somehow never seem to come out right, testing has become a quiet thrum in the background of daily life, one that sounds faintly unpleasant and spurs a desire for distraction.

The testing octopus has long, sticky tentacles, but our students and teachers have been trussed up in those tentacles for so long that the drama of their capture is now old news. In America, old news too often becomes non-news. We were outraged at the lead levels in Flint, Michigan last year. Will we be as outraged in a few years when the long-term effects of those lead levels begin to impact our schools?

Americans today are assaulted with bad news. We grapple with Flint, bankrupt Chicago schools, major storms, terrorist trucks in France, college costs, Ebola and Zika outbreaks, global warming, an erratic stock market and suspicious Chinese puppy treats, all part of a nonstop feed from our phones and computers, a nonstop info-barrage that dulls normal reactions to real problems. Humans are only built to sustain so much outrage. Then we tend to look for the chocolate and check the DVR.

Nevertheless, I can’t keep whining without suggesting policy changes. In particular, our schools need to cap total testing days. Total testing days in America’s schools border on absurd. Government requirements vary from state to state, but any requirements that result in more than a week of standardized and benchmark testing should be adapted or repealed. If state governments want to do something useful for a change, they might pass laws capping testing days.

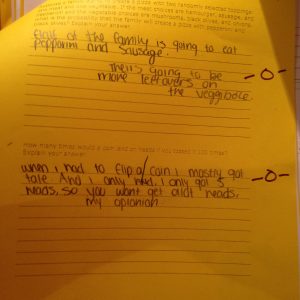

This has to stop. We must assess student progress, but administrators and bureaucrats also need to remember that every assessment represents one more missed teaching opportunity. Our assessments may be wearing out many students, too. I vividly remember one Monday morning after PARCC® testing. We had finished PARCC®, but I was expected to give a math unit test that day. I pulled out the bubble test sheets, each with its student’s name at the top. I pulled out extra number two pencils. As I started to pass out the test, students stared at me, some in apparent disbelief.

“ANOTHER TEST!!?” A girl wailed loudly. “WHY??!”

“I DON’T KNOW!” I almost shrieked. That silenced the class. I had gotten pretty close to some personal breaking point at that moment, and the class sensed this.

After a brief pause, I continued quietly.

“We have to do this. It’s required. All the math classes have to do it. Somebody wants the data. Don’t worry about it. Do the best you can. It won’t hurt your grade, I promise.”

I kept passing out those tests and answer sheets, wasting one more hour of our precious time. I knew in advance that my students could not pass the test I was handing out. I was keeping a number of them afloat with extra Saturday morning tutoring (unpaid, and I drove an hour to do it) that enabled some to pass the weekly quizzes, but no one ever had or would pass a unit test to my knowledge. If anyone did, I’d put that success down to luck picking bubbles on the front part of the test, a lottery win of sorts. Did anyone all year get full points on a single short-answer problem? Maybe not. I just kept putting zeros beside those short-answer problems with a rare, partial credit “+1” here and there. Fortunately, I did not have to hand the unit tests back to the kids. I handed them to academic coaches who took the tests to an upstairs nook where the bubble portions of the tests were graded and the final data recorded.

Every “unit test” hour was wasted time in my view. Our own benchmark tests showed those tests were at least three years above most students’ level of understanding. Reading difficulties for bilingual and special education students contributed to the debacle of those unit tests. I’m not sure if translation was allowed – I asked and got a wishy-washy answer, and then decided not to pursue the matter further for fear someone would give me the wrong answer – but sometimes I would help with reading those tests. I know the special education teacher did too.

I remember a professional development meeting where a speaker said one of those truths that stick with you.

“You should always go over any quiz or test that you give. If you don’t, you should be ashamed.” He looked angry at the thought of even skipping that last step.

But we never went over those unit tests. We had too much other mandatory material to cover and too many other weekly quizzes to go over. Besides, the grading was being done by coaches who were sometimes behind. Going over a test or quiz weeks later provides little benefit. Going over quizzes that everybody failed because they could not understand the test provides little benefit –unless you have a fairly large chunk of time that can be used for remediation and explanation. Given the test and quiz schedule, I did not have enough time to teach what had to be taught, much less to provide that remediation.