When the hysteria about recent math and reading scores kicks in, we must be ready to defend whole child education. We have a great deal to teach in the near future, only some of it academic in nature. Math facts and vocabulary are essential — but our emotionally buffeted students will need more from us. We have to prevent test score hysteria from preventing vital social/emotional learning.

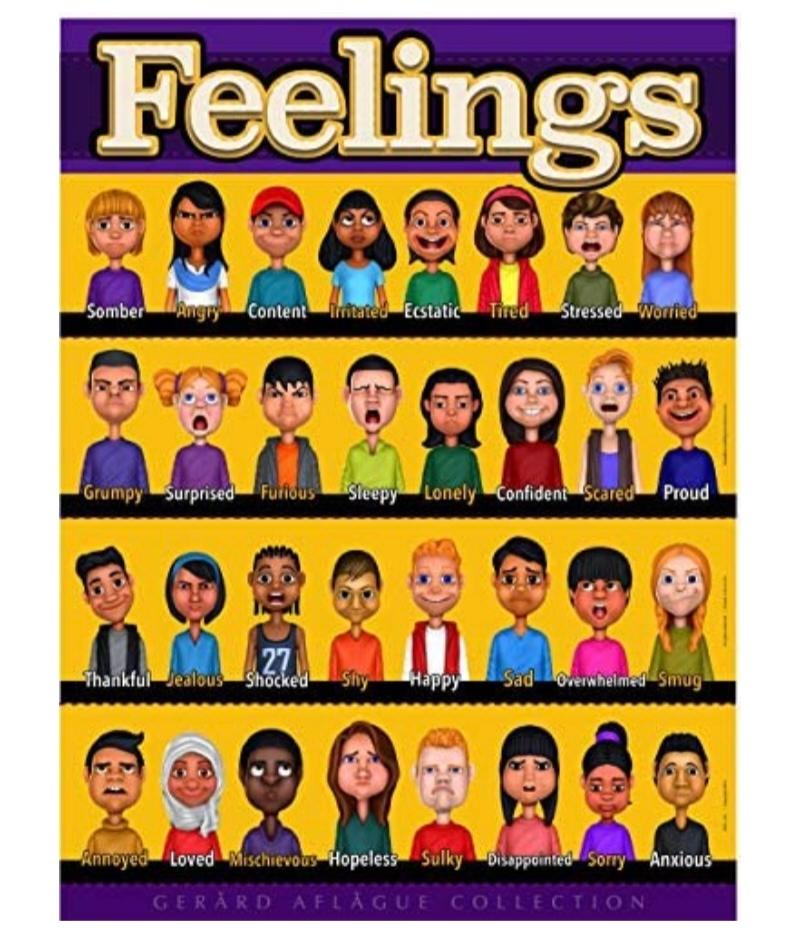

Parents and teachers often end up discussing feelings with young children. How do you feel? Are you angry? Are you sad? Why did you throw your books on the floor? Feelings are naturally part of an early and sometimes later elementary curriculum, whether formally recognized or not. Here is a visual aid from the Gerard Aflague collection on Amazon, a poster adorning many classroom walls. Various feelings’ posters can be found to help young children link expressions to emotions to words.*

I stumbled into this post this morning, a stray thought in response to a Facebook comment. Yes, we talk about feelings with small children often. But I think it’s easy to fail to realize that sometimes kids don’t have the right emotion connected to the appropriate word when they are conversing with us. Our sad may be their lonely. Our angry may even be their sad, especially if mom says a behavior is making her sad when her face is conveying anger instead. Maybe mom is about to be late to work due to an unexpected kitchen mess, and she is verbally managing her anger but not quite keeping the exasperation out of her tone and expression. Sad can be very tricky.

Kids learn to connect the right words to matching emotions, but trial and error are part of the process. Making the right associations may take years. Kids often begin using words on the feelings poster before they have recognized and internalized true meanings. My take from this fact is simply that what a child said may not be what they mean or believe when a topic as complicated as emotions comes up.

That was my first morning thought. My second thought was that the masks will be making social/emotional learning harder. People are getting good at smiling with their eyes, creating that small crinkle that says, “I really do hope you like that latte and have a good day,” but masking up will slow emotional learning down, as kids try to associate partially-hidden expressions with feelings.

Readers of this blog know that eduhonesty.com is 100% pro-mask, with the understanding that rare exceptions must be made. Children with autism, for example, may be unable to manage a mask. Generally, though, classrooms must put student, family and employee safety first — and the most reputable research does show masks help.

My last thought was that students in 2021 have a great deal to process. The youngest kids may be the luckiest ones. Our kindergarten and first grade students have only known pandemic schools. Older kids are adapting to changes that mostly make their lives tougher, both intrinsically, because those COVID-19 protocols are demanding, and extrinsically, because once they socialized freely and they remember a time when germ-awareness was almost nonexistent in their lives.

So amid all the educational issues on the table right now, why post about teaching feelings? I am trying to get out front of the panic likely to come at us as educational leaders stare at their fallen test scores. As we plan remediation for COVID-related learning loss, social-emotional learning may easily get lost in the mix because of the sheer amount of catch-up to be done. I want to encourage parents and teachers to keep the spotlight on social-emotional intelligence. How do you think Woody feels? Why do you suppose Buzz did that? Is Mary Poppins really upset? What makes you think she is (or is not) upset?

The social-emotional work I am talking about is already being done by parents and teachers everywhere, but I thought I’d pull that work into the foreground right now. The tests are going to come back showing learning loss from the last two years — maybe a great deal of loss in our hardest-hit schools. I can easily see fear pushing districts to work on mathematics and English almost entirely, to the exclusion of other topics. That would be a huge mistake — another version of the same mistake we have been making since the inception of No Child Left Behind nearly twenty years ago.

Our children are children — not merely sources of data that must be prepared for an annual test. Yet year after year, we keep stealing children’s time as we replace instruction with testing and test-preparation, all while depriving children of helpful remediation because “that topic is not on the test.” See “Opting Out: Because Your Child’s Teacher May Get NO Useful Information from that Test | Notes from the Educational Trenches (eduhonesty.com)” for this blog’s recommendation on that testing.

Yes, the missing words and math facts from interrupted instruction matter a great deal. However, so do the direct and indirect emotional impacts from our broken instruction. These last two years have been the wildest, weirdest years many of us have ever seen, and ignoring that strangeness helps no one, especially children who desperately need us to help them understand and process what is happening in their lives.

Hugs and thanks to all my readers, Jocelyn Turner

*Not all feelings posters are sufficiently diverse, I’m afraid, but I trust my readers to look out for their classrooms.