“It is not our abilities that show what we truly are. It is our choices.” Wisdom from Albus Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

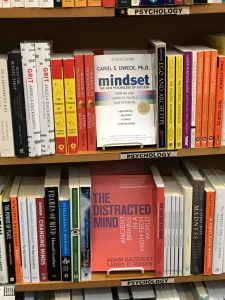

Carol Dweck wrote a book, called Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, and her thoughts now sit on bookshelves in paperback form, owned by almost every teacher I know. I love how Dweck channeled Albus Dumbledore. It is not now — and never was — our abilities. It’s our choices, Harry, good and bad. It’s our ability to stand up when events knock us down. It’s our courage as we reach for the sword, listening to the basilisk slithering in the background.

Mindset is how a person views their personal skills and inclinations. Dweck’s book describes fixed and growth mindsets, observing that beliefs can limit our success or can grow that success, based on internal messages we give ourselves. Schools unsurprisingly have embraced Dweck’s ideas because of their potential for helping students learn. (Of course, some schools might embrace basilisks if they thought being terrified by basilisks would improve their test scores.) Change your words, teachers tell students, change your mindset.

Here is today’s question: How are we managing work on mindset while also managing online and hybrid learning? Or guiding kids through in-class cleaning procedures and new protocols?

For parents and nonteacher readers, the following is a short explanation of fixed and growth mindset. Students with fixed mindsets believe they possess a certain level of intelligence or an established type of personality and, well, that’s the end of the story. A fixed mindset limits potential mostly because it shuts down effort. Why strive to be excellent if you are “not smart”? Why work on your self-awareness, work habits or creativity if you cannot change the fact that you are “not good at school”? Our ability to rise to challenges depends on our confidence and resilience, That kid who has concluded he or she is “not very smart” or “not good at school” is likely to conclude that individual choices don’t matter much — fixed mindsets don’t allow for much hope.

Even stronger students may suffer from a fixed mindset, becoming fearful that they will lose their position at the top of the class. The fixed mindset makes every day another chance to fail, over and over again, as any negative feedback comes to be seen as an attack, rather than constructive feedback. Especially in this time of Common Core, Common Core curricular remnants, and toxic standardized testing, even stronger students may expect to be unable to succeed at major tests and assignments.

I’ll ask readers to pause here and put themselves in the shoes of that child with a fixed mindset: You can always lose. For a child who struggles academically, any chances of winning the academic game may seem much smaller than their chances of losing. To more sensitive children, those odds may appear astronomically high — so high that effort seems pointless.

Having a growth mindset helps encourage learning and effort. When mistakes are seen as chances to improve, instead of a long series of blunders, a student can focus on improving performance without feeling defensive. When a child believes he or she can improve with effort, effort becomes potentially rewarding. Practice becomes a strategy to improve performance. Feedback becomes a source of learning instead of shame. The end goal of cultivating a growth mindset is to create passionate learners who will keep working both on good days and bad.

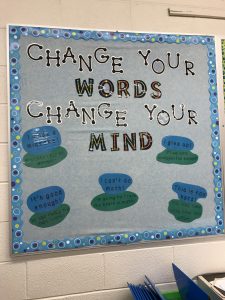

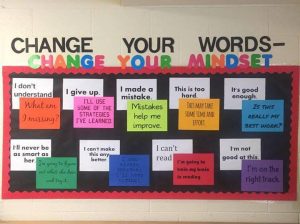

When in school, those bright, cheery mindset bulletin boards are beacons of hope to some students. The right questions and comments at the right time can rescue an effort gone wrong: “What am I missing? I’ll use some of the strategies I’ve learned. Mistakes help me improve. This may take some time and effort. I can always improve; I’ll keep trying.” One of my personal favorites is, “I’m going to figure out what she does and try it.”

Especially when students are sitting in their own kitchens or bedrooms, how are we to inculcate growth mindsets? Kids are still waiting to start school in person in some areas. In others, they are going in and out of face-to-face learning. Mindset can easily fall entirely off the radar in this set-up.

As we post assignments in cyberspace, we must convince students to believe that diligence will help them get ahead academically. We want them to ask themselves: “Is this really my best work?” “Is this what the teacher wants?” “How can I make this better?”

Or maybe we simply want them to lead with something less lofty, such as, “O.K. I’m frozen again. How can I get back into class fast?”.

What are the messages for this new and scary time? Tech talent, patience and the quality of available hardware vary greatly. What are the right messages to keep students moving forward? Here are a few off the top of my head:

“I can make this laptop work. I can figure it out.”

“I can find/finish/submit the assignment. If I have a problem, I will ask my friend Freddy. If he can’t help, I will ask the teacher.”

“I learn so much about technology when I have a problem with Zoom/Google Classroom/Your-Platform-Here. I am getting better all the time.”

“Online learning is helping me to learn how to work independently. I am getting better all the time at using Google.”

“I am resourceful at finding information even if I cannot just raise my hand for help. Getting to work on my own is preparing me for high school and college.”

Eduhonesty: Those mindset messages were an underlying thrum in many classrooms. Teachers understand that mindset is the self-image of a child — and mindset is malleable. That’s one reason why good teachers are careful with criticism. It’s why the red pens have mostly gone away and why retakes have become steadily more common. I don’t want “Freddy” to give up on mathematics. I’d rather he kept adding and subtracting fractions until he knew how to find the common denominator; if a retest will encourage him, he’s likely to get that test.

Here are a few suggestions:

- If you have a mindset board in your classroom or the hallway nearby, take a picture of that board to send to the kids and recommend they print it if possible. If they can’t, I’d email or even snail mail a picture of that board to the kids.

- Flash your mindset board onscreen every so often.

- Discuss the board and how it should be adapted for this different time. What should the board look like for online learning?

- Depending on the grade and subject you teach, creating a new mindset board for the 2020 school year might be a useful and fun assignment.

- Remind students that mindset work is not just for school. Mindset work can be used for everyday life. Ask them how they could use this idea to make themselves feel better right now. “I feel bad I can’t see my grandma” could become “My grandma will be so excited when I zoom/text/call her.”

Parents and others, I will recommend Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Carol S. Dweck (2006). Ballantine Books.

Carol S. Dweck (2006). Ballantine Books.

Mindset: The New Psychology of Success is not just for school. It’s for hard times. It’s for turning around attitudes that are dragging us down when circumstances have spiraled out of our control. It’s actually a perfect book for 2020. In Dweck’s words, “the view you adopt for yourself profoundly affects the way you lead your life.” While the book leans heavily into explaining how to become more successful at parenting, business, school and relationships, it focuses on a concept that can help get anyone through tough times: Change your words, change your mind.