According to Education Week, only 20% of U.S. students are currently learning a foreign language, according to an article at http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2017/06/21/just-20-percent-of-k-12-students-are.html. Education Week adds that, in at least two dubious states, “fewer than 10 percent of students are studying a language other than English.” The census now has nearly 1 in 5 Americans speaking a language other than English in the home, but you’d never know that from looking at the American foreign language curricula.

That one fact taps into an educational crisis that has been flying below the radar, eclipsed by our focus on English and math scores we attempt to close — or at least narrow — the achievement gap. Foreign language teaching ought to be thoroughly integrated into our curricula. It’s not. Many elementary schools have no language studies or only the most rudimentary Spanish. In middle school especially, often today it’s “Would you like to take Spanish, Spanish or Spanish?” Spanish is now the sole language taught in the high school in the district from which I retired.

Um… Real world, anyone? Spanish is handy and I love it, don’t get me wrong, but we can say the same about potatoes. Potatoes are marvelous, but who would serve an endless diet of nothing but potatoes? Who is planning the foreign language menu?

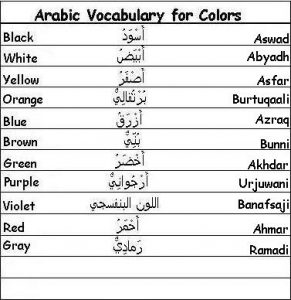

Eduhonesty: America needs to cultivate speakers of Middle Eastern languages. Languages like Arabic are rarely taught, despite the fact that these languages have become critical to national security. In the real world, as of 2014, Arabic has become our nation’s fastest growing language, seizing that spot from Spanish. We still have more Spanish, Chinese, French and Vietnamese speakers, but Arabic has been gaining fast. Arabic trails behind Spanish as a source of English-language learners in our schools; we have over 110,000 students in the U.S. who call Arabic their home language.

Where are the courses in Arabic then? Many more students in this country are taking Latin than are taking Arabic. (Not that we are teaching much Latin.) Still, we are teaching students how to write translations of “Marcus Tullius Cicero goes to the forum” in a dead language that nobody’s sure how to pronounce, when instead we need to teach

Less than 1/4 of one percent of America’s students are learning Arabic. That’s shortsighted and foolish. Perhaps the POTUS has contributed to this crisis with his anti-Muslim sentiment, but the problem of our paltry foreign-language offerings existed long before the POTUS. In August 2015, Houston residents protested against a planned Arabic Immersion School funded by the Qatar Foundation International. The very word “Qatar” scares many Americans, at least those who follow the news, and understandably. But NOT learning about Qatar and its language will NOT help the United States.

Less than 1/4 of one percent of America’s students are learning Arabic. That’s shortsighted and foolish. Perhaps the POTUS has contributed to this crisis with his anti-Muslim sentiment, but the problem of our paltry foreign-language offerings existed long before the POTUS. In August 2015, Houston residents protested against a planned Arabic Immersion School funded by the Qatar Foundation International. The very word “Qatar” scares many Americans, at least those who follow the news, and understandably. But NOT learning about Qatar and its language will NOT help the United States.

We are more peaceful with the idea of learning Mandarin Chinese, admittedly a small bright light in today’s language offerings. The US-China Strong Foundation aims to have 1 million Americans studying Mandarin by 2020, and the study of the world’s most commonly spoken language is rising. Nationwide, we now have over 200 Mandarin dual-language programs in K-12 schools, a reassuring increase over 2009, when only about 10 such programs could be found.

I have recently alluded to the opportunity costs created by our test- and data-oriented discussions. While we debate tests and data, foreign language offerings fall off the table. Music takes a plunge. Pottery shatters and even the American Revolution gets shortened into some brief skirmish with soggy tea.

What are we sacrificing as we focus on the numbers?

P.S. The issue that never got off up the floor and onto this particular table — lucky students in wealthy districts may have five or more languages to choose as electives. America’s less-financially-fortunate students too often have to hope that the funds for languages number two or three have not been diverted into extra benchmark tests or new software programs designed to provide more standardized test practice.