When we take our special education students, bilingual students and our so-called “regular” students and force them all to travel the same path to prepare them for the latest version of the Your-State-Here State Achievement Test, we end up wasting many hours of their time. We may be teaching something useful to these students – and we may not — but I go back to the issue of opportunity cost.

Everything has a cost and not all costs are measured in obvious numbers such as teachers’ salaries or bussing fees. One cost of teaching to the test is the material not taught, the material not expected to be on the test. As testing becomes more rigid and administrators become more focused on the tests, this cost grows higher. We can’t quantify this cost and the cost differs from student to student. The cost to Maddie, who hopes to go to medical school, may be minimal or nonexistent. We may be teaching exactly what she wants and needs.

But what if Reggie in special education is getting next to nothing for the time he is investing in school? When test material is set years above and beyond Reggie’s understanding, instruction related to that material will be outside his understanding. Yet administrators today will sometimes insist that bilingual and special education classes present the same material and give the same tests and quizzes as regular classes because that material is the material expected to be on the annual state test, the test on which those administrators are being judged.

Even with differentiation and scaffolding, Reggie may simply be lost as his teacher spends day after day on mandatory material that he cannot put into any context and therefore cannot comprehend. Most probably, Reggie cannot read the grade-level textbook he has been given. His teacher may be slogging through that book regardless, having been told that alternative textbooks are not allowed. In the meantime, Reggie is not receiving remedial reading instruction. He is not learning the math he might understand. He is not receiving life skills instruction.

The phrase, “You can’t get there from here,” comes to mind. I can differentiate and scaffold to teach my regular 7th grade students beginning algebra. No differentiation or scaffolding will help them to learn differential equations, however. Once I venture into math at this level, no path exists between what they know and what I am demanding that they learn — at least none that does not require multiple years of instruction. For some of our special education students, that 7th grade math might as well be differential equations. But last year I watch as those students were forced to tackle Common Core math set at their putative grade level, rather than their actual learning level.

The missing piece omitted from the big equation in this scenario? All the material that those special education students were ready and able to learn that was never taught while a pie-in-the-sky set of Common Core-based, 7th grade tests came at them instead. Somehow, educational administrators and leaders need to get opportunity costs back into the equation as they push students to learn the One-Curriculum-To-Rule-Them-All.

Eduhonesty: I am guessing some readers don’t believe what I just wrote. What is happening to Reggie here seems too improbable. But I lived through this story last year. I assure readers the above events occurred. The special education teacher for my grade was required to give the same tests and quizzes to her students that the regular students received, a fact that led to her doing almost nothing except teaching to future tests and quizzes. Remedial instruction that should have happened never did because almost no spare minutes existed between bouts of test and quiz preparation.

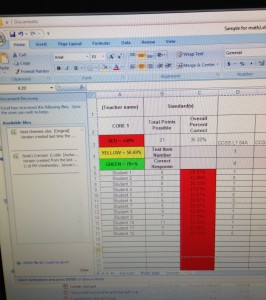

After she gave the tests, this teacher graded the tests and presented her results to the entire math department so those results could be put in a spreadsheet showing the results for all classes and teachers. Those spreadsheets were color-coded. Green meant “Go!” and stood for a successful effort, sometimes seen in regular classes. Red meant “Warning! Fail! Your students screwed up!” Often the special education teacher’s students formed a large, red block in the middle of the spreadsheet. Bilingual tended to bleed across the spreadsheet as well.

I offer this as another example of test craziness and another reason why high-stakes testing needs to go.