“An undefined problem has an infinite number of solutions.”

~ Robert A. Humphrey

I want to take a break from big cities this morning and move from the macro to the micro world again. The above quote resonated with me immediately, although I am honestly not sure what Robert A. Humphrey intended to say. I know what I took away from his utterance, and I’ll put that in my own words: Leave the teachers alone and they can solve many of our current problems.

Boxes, boxes, boxes, We are building data, data walls and spreadsheets for administrators. We are changing our instruction to match the new Common Core standards, despite zero evidence that our previous state standards were any sort of a problem, except for the effect of differing standards on standardization of data. We are attending endless meetings to prepare our matching instruction, share our data, and discuss new standards. We have extra meetings to discuss using the new Common Core-aligned books that some students cannot even read. We add meetings or professional development on developing college-readiness and reducing absenteeism. Etc.

All of these problems represent real problems. Some new solutions to these problems are creating their own new sets of problems in my book. But my problems are not Sally’s problems are not Fred’s problems. Why am I wasting my time in the absenteeism meeting if my class pretty faithfully turns up every morning? I may have a useful contribution or two for other teachers, but I’d like to hammer my favorite nail: All of our meetings have an opportunity cost. What could I be doing during that meeting that will have almost no effect on my own classroom? I could be improving my Jeopardy game on the solar system. I could be creating individualized materials for my autistic Anne-Marie. I could be calling Darnell’s mom to talk about his sudden change in behavior over the last few weeks. I can solve so many problems — but my ability to do so has been adversely impacted for years now by requirements that choose the problems I should address — problems which I may or may not be encountering, problems which may be blips on my personal radar even if they represent an incoming attack for other teachers in other places.

Each teacher has his or her own set of problems during the instructional day. In my classroom, Darnell’s moodiness may be a much bigger problem than statewide absenteeism rates. I should be left to work on helping Darnell. As far as standardization of learning standards and instruction, in a time of increasing diversity and rapidly changing demographics, rather than putting teachers in pre-approved boxes, I am convinced we should leave our teachers alone. Newly-arrived Rima from Syria should not be receiving the same instruction as Kyle from Duluth. Historically, our teachers decided how to teach their classrooms and had a great deal of voice in what to teach as well.

For Anne-Marie, Kyle and Rima’s sake, I wish we could return control of the classroom to the classroom teacher.

Eduhonesty: Some administrators and government leaders would reply that, of course, I ought to be individualizing instruction for my three students above. What those administrators and government leaders seem to miss is that if I spend 220 minutes of meetings during a week — the absolute minimum last year, and sometimes the amount ran over 300 minutes — that’s potentially 5 hours or more lost (depending on the topic) from instructional preparation and individualization during the week if I am a rank and file teacher. If I am a team leader or coach, with extra meetings, that amount may be considerably higher.

My most effective instructional year ever occurred years ago when I had two planning periods and almost no meetings. I was free to spend time figuring out exactly what my individual students needed and preparing individual sets of materials. If we go by annual test scores, my students had an amazing year.

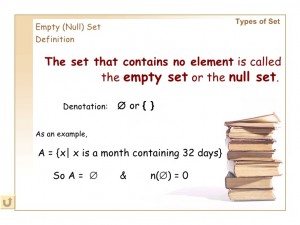

I’d like to rephrase Humphrey’s statement. I believe, “A too-well defined problem may have few or no solutions.” Thinking about this problem mathematically, we can put so many restrictions on teaching and preparation time, that we are no longer creating solutions; instead, we are preventing solutions. As we add more and more terms to our equation, eventually the only solution to our problem may be the null set.

For those whose memory of past math classes has gotten a little hazy, the null set is also called the empty set, the set that contains no elements. The null set can arise naturally when we place too many restrictions on sets. An example of the null set in education might be “the number of students reading at third-grade level who can pass a Common Core-based, mathematics quiz or test filled with story problems designed to stimulate critical thinking in a test written a seventh-grade level.”

I was required to give too many of those tests last year, wasting colossal amounts of my time and my student’s time. I shudder to think of the effect of those ridiculous tests on student motivation and enthusiasm for learning. I’m not sure what problems the administration was addressing with those tests, but I’m sure we’d have all been better off if we’d left my classroom’s problems for me to define. Even if I’d been popping Xanax while talking to tiny, scaly, lizard-like aliens lounging in my bathtub while I created classroom instruction, I could hardly have done worse. Even if I had been arranging aluminum foil on my head to keep the lizards from invading my thoughts, I suspect my instruction would have made more sense. I honestly could hardly have done worse by my students than I did by giving them those tests. At least the lizards and I might have had a sense of humor.