If I can work a happy thought about today’s education into the end of this post, I will, but I think I am about to take my rocket in another direction. This post will be about real kids.

So there I was, with my last year before retirement stretching out before me. While I had not planned to retire early, I had landed in one of those magic years where retirement might make sense, and as the months went by, retirement made more sense by the day.

The state had taken over my district, and desperation was running rampant. District leaders were standardizing my schools’ 7th grade curriculum to match the 7th grade Common Core curriculum. Teachers were expected to give mandatory tests and quizzes based on the Core, using materials chosen to match that test-determined curricula. We had shoved the bar dramatically upward. In concrete terms, I was expected to teach 7th grade mathematics to bilingual students in classes that were averaging a 3rd-grade level in mathematics and sometimes an even lower level of English-language learning.

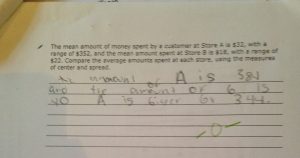

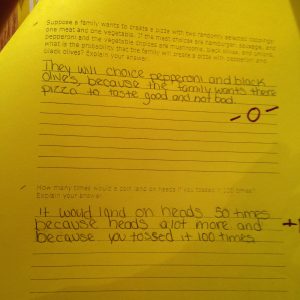

What tutoring time I had was skewed heavily toward expected test content. I was meeting students at McDonalds on Saturday mornings for extra tutoring and quiz retakes – so many quiz retakes. How did students pass their classes? They could retake quizzes. And they did. They retook and retook quizzes until they finally got them right. But were they learning what they needed to know? Could they apply the specifics of problem number six to a broader use of probability, for example? In some cases, the answer to that question might have been yes. In others, well, “Diego” had finally memorized problem six.

In the meantime, essential remedial instruction was not occurring. Teachers in lowest-level classes did not have close to enough time to fulfill Core requirements. Where was time for remediation going to come from? I worked that remediation in as often as I could, and sometimes got in trouble when I was caught remediating. But that’s another story.

Too few educational leaders have been asking critical questions: What if our students are unready for a chosen curriculum? What if their own test scores show they are four or more years away from being ready for the year’s standardized test or the chosen set of tests and quizzes for the year? What if the tutoring they require has nothing to do with their new weekly tests and quizzes, or that annual test, a test coming at them like a proverbial freight train, a large, resounding failure to finish their school year? How will these students learn the desperately needed fourth, fifth and sixth grade mathematics they previously failed to absorb?

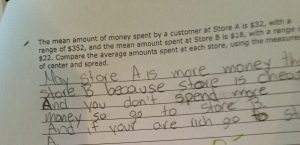

America has many, many students testing below grade level. Some middle school and even high school students are taking benchmark tests whose scores place them at early elementary school levels. I want to highlight effects we shove aside and ignore as schools push to meet test targets: For the student who struggles and often fails the many tests and quizzes in the year’s pipeline — tests and quizzes linked to a curriculum that may be neither realistic nor age-appropriate for that individual student – today’s school has become a profoundly depressing place, punctuated by frequent failures that mark the year’s best efforts. After too many such failures, I have seen academic efforts sputter to a sad halt, sometimes replaced by mild but sustained misbehavior.

Why does a student who started on track in elementary school begin regularly misbehaving in middle school or even earlier? Hormones are sometimes blithely thrown out as an explanation, but many excellent students undergo identical hormonal changes. In the academic research and in my experience, one of the best “predictors” of misbehavior is being out of sync academically with peers, especially for students who have fallen behind.

Falling out of academic sync with peers may not cause misbehavior – although I am convinced this is sometimes the case – but I can safely say that research shows a strong correlation between misbehavior and academic failure. Whether failure leads to misbehavior, misbehavior leads to failure, or some combination of the two, with or without additional challenges thrown in, misbehavior and academic failure go hand-in-hand as we tease out factors that lead to overall educational breakdown and dropping out or failing out of school. Why are we graduating students unable to write a college paper or figure out a loan? Because those students “dropped out” — even when their bodies kept occupying desks.

Moreover, I have become convinced that furious efforts to raise standardized test scores ironically are creating misbehaving students, often in tandem with the additional one-two punch of course failures or near-failures in English and mathematics. As we stuff classrooms with students ranging from a first-grade level to a ninth-grade level academically and then hand those students common or nearly-common preparatory materials chosen because those materials are expected to provide optimal test preparation for a specific set of grade-level tests, we create a group of lost students who simply are too far behind to succeed with the material they have been given. A student reading at a second-grade level and doing math at a third-grade level cannot do seventh grade work on any regular basis.

Period. And the sooner we face this fact, the better off we will be. Remediation is not optional. Time for remediation cannot be taken away and replaced with “higher standards.” Those standards should be taught. But if we want to teach those standards, we will have to provide students with more than a 7 1/2 hour day and a 180 day school year.

How can we close the achievement gap? I see only one possible path to success. We have to provide more instructional time to the students who have fallen behind. A few extra hours of tutoring after school or on Saturday will not accomplish our goal. If those hours could work that much magic, we’d have many more success stories to point to today. Students can’t cover four years of missing material in a few extra hours a week. They might have a shot with an intensive, obligatory summer program, however.

Our students don’t need more rigorous, new standards. The old standards are usually more than rigorous enough to prepare them for college and life. What they require is a school year that provides enough time to catch up to the standards they previously missed and are still missing.

Yes, my solution will be expensive. I suspect that’s why we keep trying Plans B, C, and D, the plans that can be most easily effected with the funding available. But B, C, and D have not worked. The achievement gap has barely budged. I’d try obligatory summer school next or an all-year school year with obligatory school during intercessions throughout the school year for those students whose data shows them to be cripplingly behind.

Half-baked, stop-gap measures are not working, and in the meantime we are making many kids feel like absolute crap with our half-thought-out solutions. I got so tired that last year I taught. I kept picking kids up psychologically and dusting them off, working to keep them in a game we all knew only a few of them could win.

I can work incredibly hard. But I can’t work stupid. And now I am one of many, many former teachers who left the toughest schools in America to make tomato risotto and write, taking advantage of my abundant spare time. I watch highly talented former English teachers sell lipstick and mascara. Some of us substitute teach. Others rewrite resumes and tutor ACT students. Some just sip piña coladas on Florida and Indiana beaches, a few years earlier than expected.

I am sad for all that wasted talent. I am sad for those men and women who are counting days until they too can retire. Mostly, I am sad for students who are being cheated by plans that no one seems to have thought through. We are teaching critical thinking as part of our curricula today. In educational administration, though, sometimes critical thinking seems lamentably thin on the ground.