I’ve recently posted ways in which that spring state standardized test hurts students. Here’s a subtle and cumulative effect that hurts teachers, one that’s happening all over the country.

_________________________________________________________________________

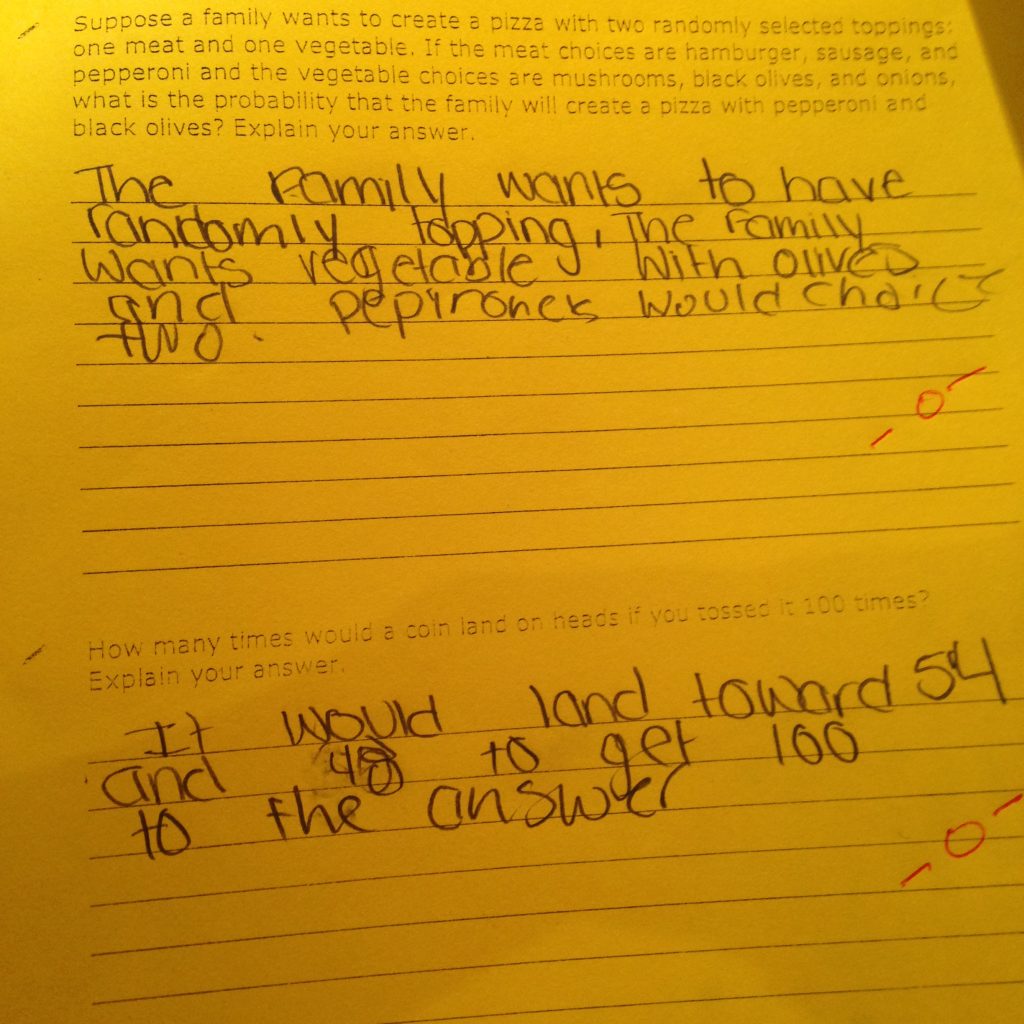

It’s a short, simple phrase: The kids can’t… Maybe it is followed by “add fractions” or “tell time” or any of a thousand-plus possibilities. And sometimes that phrase is absolutely true. Among my most aggravating teaching moments were those when I tried to explain that my kids could not, in fact, do material that the administration had nonetheless required because “it’s on the test.”

Still, this phrase should be viewed with caution and trepidation. “The kids can’t” has the potential to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. I present this as another reason to opt-out and shut down the madness of today’s testing culture, a reason I don’t think I have ever read elsewhere. Let me try to explain my slightly convoluted idea using an example:

I am the teacher. The administration has told me that my 4th period class, in which one student is testing two years below grade level and everyone else is at least four years below grade level, must do grade-level algebra problems because these problems will be on the state standardized test in late spring. Very limited remediation time or support is available. I may naturally look at this scenario and declare, “But my class cannot do these problems.”

I am right. Especially with all the required tests going on throughout the year, I don’t have a realistic shot at pulling this group up four full years mathematically in a few months. I might be able to find a magic carpet for one or two gifted kids who just arrived from Cambodia or the like, but basically my administration might as well have asked me to teach the group to plan the next spacecraft landing on Mars.

My question: what happens if this scenario repeats too often? When I am repeatedly asked to teach a process because “it’s on the test” to kids who are years behind grade level when they arrive in my classroom, I find myself repeatedly saying “My kids cannot do this.” I may be right. The kid who cannot add fractions cannot do eighth grade math. That’s simply a fact. The fractions must come first. Remediation must come first.

Let’s skip all the issues involved in catching up the children who have fallen behind. I want to look at one aspect of this scenario: I keep saying, aloud or to myself, “the kids can’t do it.” After awhile, I may come to believe what I am saying, EVEN WHEN IT IS NOT TRUE. The kids can’t do “it” is a self-fulfilling prophecy when I do not teach “it” because I have already concluded — perhaps correctly but perhaps not — that “it” is impossible.

This is a mindset issue, but not one that simply results from selecting unfortunate words. If I have a group of kids that mostly cannot clear a four-foot high bar, being told that I must prepare them to clear an eight-foot high bar represents a disconnect with reality. Too much disconnection and my go-to internal messaging may go haywire. In place of “this is what we must do to master Topic X,” I am regularly starting with “the kids can’t…” instead. Once I get stuck in that place then, yes, they can’t. They can’t because I won’t even try to get them over the bar, viewing that effort as essentially futile.

This all began with that spring standardized test and an administration desperate to pick up points on that test — so desperate that rational instruction fell by the wayside. What happens to the teacher who keeps being told to force her students to leap tall buildings in a single bound? One thing that may happen is a subtle attitude shift from “we can do it” to “my students can’t.”

“My students can’t” is not a phrase we want teachers to be using often, even when it’s true, maybe especially when it’s true. Students sense when a teacher believes in them and they sense when he or she lacks confidence in their ability to complete the latest standard projected up onto the whiteboard. They may not understand that their teacher has simply made a rational judgment about an irrational academic expectation. Instead they may think that their teacher lacks faith in THEM. Meanwhile, we are wearing a groove into that teacher’s set of self-messages, one that starts with “my kids can’t…”

Those spring standardized tests work directly against rational expectations based on past performance. After a teacher has been told to plan another Mars landing too many times, that teacher may give up on teaching topics that remain eminently useful and doable. That teacher didn’t exactly lose faith in students. Instead, he or she lost faith in rational curricular planning.

But the effect of this loss of faith will be the same regardless of its source. Set the bar too high and everybody may fail. Some kids will jump higher. Other kids will quit and walk off the field. Some teachers will begin stealth teaching — teaching what their students should learn next in a rational universe rather than whatever pie-in-the-sky standard is pasted on the board. Other teachers will try to teach those standards because that’s what their group is expected to be teaching, whether that content makes sense for their particular group or not.

Reason #42 for opting out of this year’s big test: When the test determines the curriculum — as it almost always does today — that curriculum may fit nobody in a special education, bilingual or even regular classroom. That results in a substandard education, potentially for every student in the classroom.

This set-up also results in a teacher who has to keep saying, “my kids can’t…” until those words sometimes create the reality they once merely described.