Why has testing spun so far out of control? The obvious reason until recently was the need to make NCLB targets to avoid government sanctions, but those targets created their own dynamics. Data-driven instruction and frequent testing have become norms. Teachers and administrators expect to hollow out regular instructional interruptions for testing throughout the school year.

In academically-struggling districts, scores may affect retention all the way up the line. When a teacher, principal, or even superintendent does not deliver improving test-score numbers, that person’s job may be taken away, given to the next person who promises to deliver better numbers. In this environment, testing cannot be deemphasized. I remember my Principal going from class to class one year to tell students he needed them to help him. He needed those scores to go up.

Multiple tests have another advantage; they provide multiple data sources to use to document progress. If MAP® test improvements show only mediocre progress, AIMSWEB® scores may come in documenting a greater leap forward. Test scores on one test may have gone up 6% in the last year, while scores on another test fell 1%. That 6% improvement likely will be included in the district newsletter, while the 1% loss quietly disappears into a filing cabinet in a dusty, interior office.

During my last year teaching, we gave multiple administrations of both AIMSWEB® and MAP®. I remember listening to my principal (another principal, not the guy who was going to all those classes) explain that she had chosen to give two tests because she wanted the better of the two to use for data to emphasize for Illinois State Board of Education representatives, who were dropping into our school regularly. I like to say we were not “on the radar.” By that point, we had been shot down. The local Board had been fired and state oversight included even classroom visits.

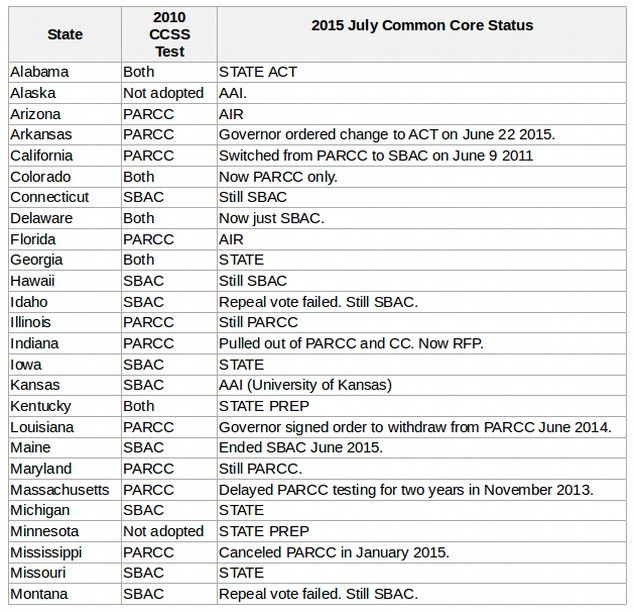

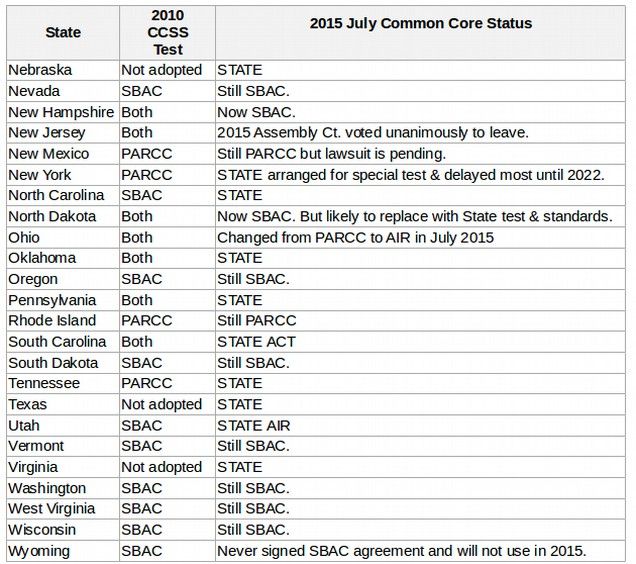

In my last year teaching, my district took two benchmark tests, each with three separate test dates for a total of six tests. In addition, students took PARCC® tests twice. (PARCC® would subsequently get rid of that second test, in response to negative feedback.) The test tally should also include mandatory unit tests written by an East Coast consulting firm, along with weekly Friday quizzes based on those unit tests. On the one hand, I would certainly be giving math quizzes and tests regardless; on the other hand, these multiple choice/short answer unit tests were written by outsiders, and their grades were calculated and used for data by academic coaches. The unit test results were not included in student grades. Quizzes were based on unit tests, not student learning levels.

All these assessments were administered throughout the school year to give the state, district leaders, school administrators and teachers feedback on how students were progressing toward meeting academic expectations. With these lost days of testing, my school was able to provide quick information to the state showing that students were making academic progress. I don’t actually remember the numbers we produced, but the school successfully reached improvement targets, at the expense of a fair amount of instructional time.

“Extra” tests may allow America’s district and school administrators to sanitize educational failures that don’t fit the desired picture. Politicians benefit from testing as well, receiving data that can be used to demonstrate a need for greater educational funding for their constituents and/or progress being made within their districts. At worst, politicians pass clumsy legislation meant to improve school performance, legislation that makes teaching and learning harder, rather than easier. No Child Left Behind instituted or at least accelerated the testing push that sucked up one-fifth of my teaching hours in my last year’s math classes.

In the end, whether we received useful data or not, I am certain that we did not receive data worth one-fifth of my teaching time. If we want to improve our schools, we urgently need to rein in testing. One-fifth of a school year amounts to 36 days — or thirty-six wasted classes for any single class group. I want at least 18 of those days back to use for teaching instead of giving absurd tests and quizzes.

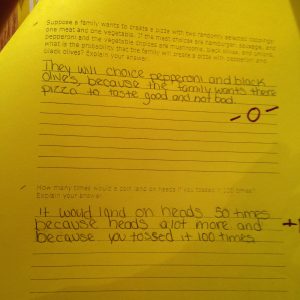

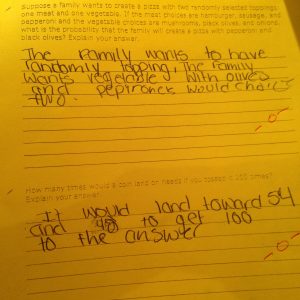

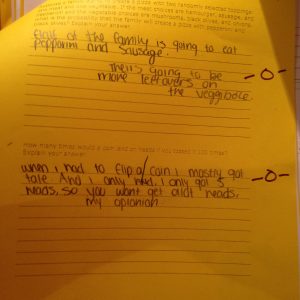

I knew in advance that giving this unit test to the kid who wrote the above was a waste of time. I would have had to chug gallons of the Board Office Kool-Aid to think otherwise. But administrators had make it crystal clear that my job depended on me doing as told.

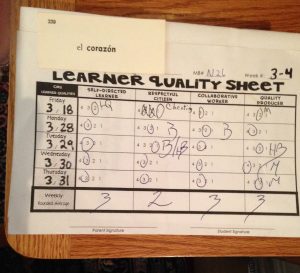

During the year of the tests, I worked furiously on math, but I also worked furiously on resiliency. I encouraged. I encouraged, encouraged, encouraged. I was the poster girl and motivational speaker for

When a teacher is teaching appropriate material, though, she should not need to keep picking her students up off the psychic floor. We owe our students tests they can understand based on material they have been taught, material that has been sufficiently reinforced before test or quiz day. Every student should be able to do well on a test or quiz providing that student has listened, worked and studied.