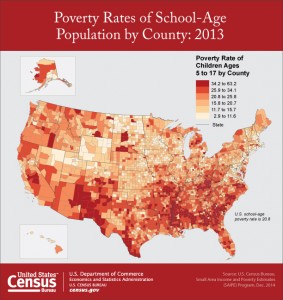

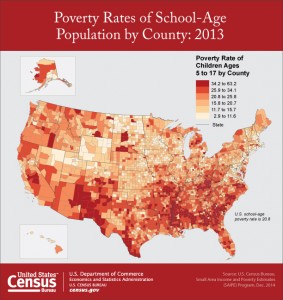

Poverty Rate of Children Ages 5 to 17 by County

This is a slightly updated replay of a post written shortly before my retirement. I don’t want these thoughts on unions to get lost in time. Unions create a power base for workers who lack power — which nowadays seems to be almost everyone putting on a work uniform.

The push to discredit unions has been underway for decades, fueled by powerful business interests, by men and women who would rather not pay any minimum wage at all. But at some point, a great many working Americans also bought into stories of laziness, ineptitude and unfairness that were used to depict unions as losers for education and other industries.

Speaking of fake news…

_____________________________________________________________________

I’d like share what may be my favorite professional development quote of all time: “Anyone who feels you’re overwhelmed, you are in the right spot. That’s the nature of teaching.” The presenter from the Danielson group had natural rhetorical flair. She had her audience at that point, all eyes glued up front.

There’s a lot of overwhelmed going around.

My students’ parents often feel overwhelmed. They share this when I call about classroom problems, explaining the difficulty of parenting while working two jobs. How do people live on minimum wage? They work two jobs and take as many hours as they can get, mostly as many as employers will allow without being required to provide benefits. Two jobs of less than thirty hours each can still equal nearly sixty hours of back-breaking labor — and I have talked to parents who worked three jobs to survive.

As I listen to these exhausted moms and dads, I think: We are not the better for the gutting of America’s unions. U.S. students knew more in the past, especially if breadth of knowledge is taken into account. Despite the dumbing down of state tests that has occurred over the last few decades — I’m sure a major contributor to the attempts to develop a national test like PARCC — the data demonstrates a decline in American academic strength. That academic strength occurred in a time of strong unions. The unions have not been the problem with American education, despite anecdotal stories about rare teachers who were protected from job loss unfairly.

Eduhonesty: I know that test-score mania and social science numbers have become tools to use to break unions, despite a total dearth of evidence that unions were the cause of America’s test-score problems. America has simply become labor unfriendly in general. But those lower scores are used to justify charters and school reorganizations, reorganizations that seldom produce desired results. The charter movement along with those fired administrations in reorganized schools have been a fact for more than ten years now. Yet test scores are stagnant and even falling in some places.

An international exam (PISA) shows that American 15-year-olds are stagnant in reading and math even though the country has spent billions to close gaps with the rest of the world. This has been true since the year 2000. The achievement gap in reading is even widening.

I refer readers to https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/03/us/us-students-international-test-scores.html for more details.

I didn’t used to believe in unions. I do now. If the nature of teaching is to be overwhelmed, perhaps teachers need some protection. When I started in this profession, I had reliable planning periods. I don’t now. There’s a planning period on my schedule, but I’ve never been able to depend on that period. After most of a year of stress and complaints by teachers, an email went out saying that Friday meetings were to be eliminated so teachers could have one guaranteed planning period. But I am teaching two subjects. If I don’t meet on Friday, when does that second, required lesson plan get done? I sometimes subbed during my planning period until we finally hired building substitute teachers (I loved that day when I was supposed to meet with the Assistant Superintendent for the District, but he had to cancel because he was supposed to sub in my school. That probably got us our building subs.)

No job should be overwhelming by its nature, not without some attempt to fix the working conditions creating that state of emotional turmoil. Overwhelmed teachers cannot be good for students. Overwhelmed teachers are defecting from the profession in big numbers, too. The estimate that half leave the profession within the first five years may be accurate. (Then again, that number may be more social science hooey. Who really knows? I know I started in my district with a group of more than 10 other, new teachers, all of whom are gone.) Why do we allow these toxic working conditions?

Many Americans need to reconsider the idea of unions in my opinion. United, American workers once created a middle class. United, we created schools that the world envied. That middle class appears to be slipping away for many hard workers. Those schools have become objects of pity and even scorn by other countries. If we don’t stand together, what will happen to the workers and teachers in this country? Who will take care of us? Not those many employers who are calculatingly keeping millions of Americans below the threshold hours for benefits. Not those school districts who are broke and can save $30,000 by replacing experienced Maria with newly-graduated Juan. Throw in required governmental purges of educational staff, and the landscape’s looking increasingly bleak out in pockets of America.

It’s time to support our unions again. It’s past time to help those workers who are working two jobs just to make the rent and buy enough food for the family. In the past, one argument against unions consisted of the idea that corporations and school districts would take care of their employees, paternally looking out for members of their organizational family. Surely no one trusts in that idea today. Where are the benefits of yesteryear? If a single one of my students’ parents is receiving those benefits, I’ve never heard about it. I’ve heard my share of sad stories, though, like the story from one mom working in the “backroom” for two years, trying her hardest to get a job “on the floor.” On the floor, they get benefits, but for many workers, that floor might as well be the moon.

I’ve got two separate posts melded into one here. Teachers are not factory workers or burger servers. The problems of teachers may overlap with those of unskilled workers, though, even if that overlap diverges at points. Still, I plan to keep this post as it is, since I think my general point applies cleanly to both groups: We need to organize. We need not to be ashamed or intimidated by the thought of organizing.

To quote one of my favorite historical figures, Benjamin Franklin: “We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

P.S. If Costco can pay its employees a living wage, I’ll submit that Walmart probably can too. Paying that wage would increase Walmart’s prices, but Walmart workers could then funnel more money into the economy generally. The demand for decent working conditions with an eventual retirement plan should not be regarded as some form of gouging.