New to teaching? New to middle school? This is a quick post to describe middle school issues that affect student success. Aside from transition issues, the pain that comes from leaving cozy elementary classrooms, students confront intimidating challenges on entering middle school. A few issues to think about before your interview:

- Organization — what does the school organization look like? What team will you be on? How are teams organized? How do they work together? When do they have common planning time?

- Organization — how will you help students with their personal organization? Oh, those lockers! By October, the papers may be spilling out, some of them completed pieces of homework that never made their way to a teacher. Paperback books will be crushed. Bananas may be oozing down the back of that metal box. One job not listed on the job description will be getting your students organized. Create a rough plan for managing that so you will sound ready if the issue arises in an interview. Emphasize the importance of helping students learn to be organized, the small details like regular, rigid adherence to the daily planner. Emphasize the family/teacher link and your plans to communicate with parents regularly when you observe organizational problems.

- Study skills — what might you do to improve/develop your students’ study skills? How can you work in techniques for active learning? How can you help students take advantage of their learning styles and best times during the day? What can you teach to help students retain material? Mnemonics, study guides and graphic organizers are favorites. Do you have a special talent for any of these?

- Multiple learning styles — how will you differentiate for learners in your classroom? How will you know your students are on target? Some answers: Pre-assess and make sure students are staying with you through regular checks such as exit slips and quick question/answer moments. Experiment with different groups so students can best help each other and learn from each other. Work with cooperating teachers to appropriately adapt materials. Communicate with home regularly to see if parents are observing problems or stressors you can manage before they spiral into ugly academic results or behaviors.

- Reading — how will you promote reading? Your intended area of teaching does not matter. Reading is pivotal to long-term school success. Teaching your students how best to approach their social studies textbook helps set them up for later success in a wide variety of classes. Think about how to work that reading piece into the interview should the right opportunity arise.

- Adolescent craziness — how will you address the extreme angst and emotionalism that some kids demonstrate in middle school? What will you do when Phillipa runs out into the hallway in tears because May told her that her she had small breasts? When Justin melts down because his hamster died? How will you manage when a pregnant seventh grader has a panic attack? Given any scenario like the above, I recommend telling interviewers you will seek advice from social workers and counselors. More serious problems should be delegated quickly to these professionals. If you don’t quite know how to address adolescent wackiness yet — you’ll learn — show a sense of humor and emphasize that you will communicate with family and other school professionals to get the help you need when the crisis arises.

Many elementary/middle/high school issues overlap. Different administrators go down different roads in an interview. But these are issues to think about before you sit around that table with the hiring committee.

Good luck!

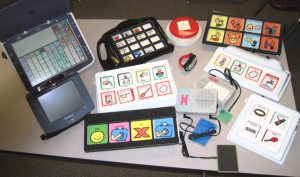

(Assistive technology that might be used by instructional aides.)

(Assistive technology that might be used by instructional aides.)