Among friends, I call this the Blog of Gloom and Doom. When I retire, I will try to balance out the blog with some cheerier content, but for now I am documenting a year and sharing my thoughts from this time.

As I write this, the news is filled with flames, shots of Baltimore looted and burnt. Internet clips show angry teenagers and young adults rampaging amid the chaos, a destroyed police car, rows of cops standing shoulder to shoulder behind shields. Facebook posts provide conflicting stories; Baltimore friends are adding clips of neighbors caring for neighbors, cleaning up the debris after the riots. MSNBC used the term “urban unrest” instead of riots, but I think that attempt at sanitizing the situation downplays the reality of that wall of fire. Euphemisms won’t change what happened here.

Eduhonesty: I believe my blog is documenting a disaster that has been occurring in American education, as testing and pie-in-the-sky expectations dismantle what was once an educational system that the world envied. As I look at Baltimore, I am struck by the fact that America’s educational system — and America’s educators — are becoming steadily more stratified. Baltimore may be paying the price.

Education still works well where I live. The schools continue to be among the top schools in the country. Graduates of these schools move on to Harvard, Stanford and Cornell, fully ready to tackle the challenges ahead of them. State laws adding new teacher evaluation rubrics, new standardized tests, and SLOs may be a nuisance, but the money and technology exists in these schools to work around the opportunity costs incurred from the laws. Students often come from stable homes (you almost have to be stable to afford a house around here) and from homes where college is an expectation. Years ago, I read that this suburb was 88% white collar and I doubt that number has changed much.

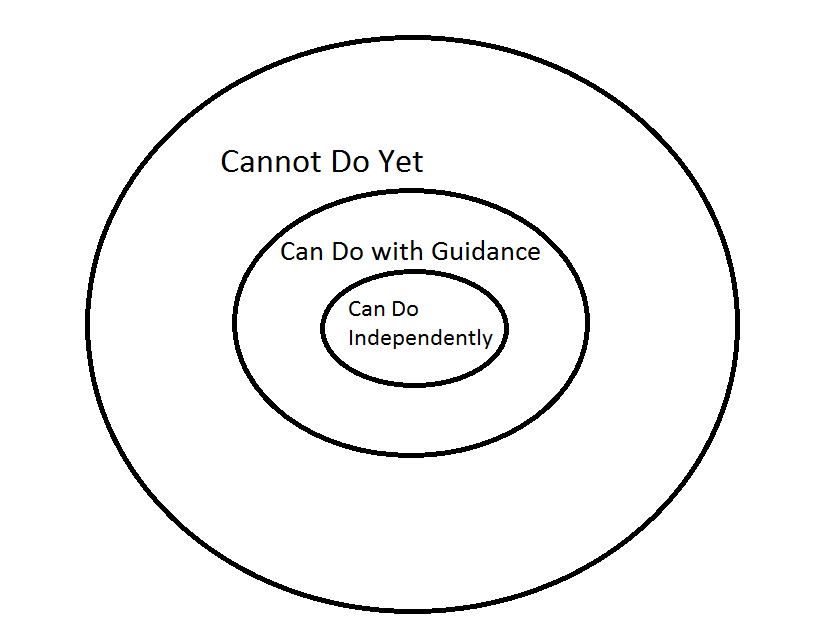

Education has not worked well where I work and I believe the multitudinous tests, in particular, are making that situation worse. If improved instructional strategies result in better academic results, as I believe they will, those results may be offset and wiped out by the sheer number of days we are spending giving inappropriate tests. Some students will still benefit. I project that students at the top of the academic hierarchy in this very poor town will make noticeable gains in test scores due to increased academic demands. But the students at the bottom are getting killed. If the material presented is too far above a student’s level of understanding, and if that student cannot get tutoring or get enough tutoring, then that student may just be killing time between tests.

I am teaching two girls who provide a snapshot of what I am saying. Their MAP scores for math show zero progress this year. I never could get them to tutoring. Their dad is often away, mom does not drive, and they are not allowed to walk. In the end, they could hardly ever stay for the afternoon and they only managed to meet me for two Saturdays. They needed extra, tutoring time that did not exist for them. At this point, they are no further ahead than they were a year before. They are diligent students so I find this quite upsetting. The math this year has been years above their understanding and learning simply did not happen. Tutoring would have helped, but I understand mom’s concern; I would not let my little girls walk through these neighborhoods alone, either, and the girls live some distance from school. In case readers are wondering, I am not allowed to drive for liability reasons and we have no late busses.

To get back on track, the challenges in this district are many. In contrast, wealthier districts have tutors, late busses, tiered math tracks, functioning computer labs with available remedial programs (ours have been shut down week after week this year for testing), and parents who regularly drive to outside tutoring schools and classes.

The burden of this test-based craziness has been falling disproportionately on urban and poor schools. I suspect that attempts to help the poor may even have done more harm than good. (If not, show me the progress from the last decade!) Teaching to the test has not yet produced improved educational results, but it has sucked a great deal of time and fun out of classroom teaching and learning. What we have in Baltimore appears to be a great number of young people without jobs and without much to lose.

Who suffers when a district spends more than 10% – 15% of its time testing? When that district keeps giving test after test that groups of students do not understand? The students where I work are hurt far more than the students where I live. Where I live, dad will hire five tutors to get that ACT score up if necessary. Where I work, the end result of all that confusing, rapid instruction, punctuated with incomprehensible standardized tests, is more likely to be a drop-out than a new tutor.

Baltimore is burning and, underneath the flames, I see the specter of a failing educational system. Those kids and young adults ought to be at work, but too many can’t find work. Too many are unready for high school, college, or anything else.

Please don’t blame the teachers. We didn’t create this test mania. No Child Left Behind did. Creating new, harsher standards for teachers won’t fix the situation, either.

I’ve wandered a bit here. Let me try for a cogent summary. The test-based mess that is American education affects different groups disproportionately. Young African-Americans, especially boys, and people who live in urban and poor school districts, have suffered more than their counterparts in wealthier districts from the damage done to education in the last 15 years.

Those kids who need help the most are the kids most harmed by America’s testing. We test, test, test these struggling urban students, showing them their failed results year after year. Is it any wonder that some of them are out in the streets instead of at work? We proved to them that they occupied the bottom of the heap. Our many, many test results repeatedly documented this sad fact for them in gory detail. Why should we be surprised that they gave up? Why should be surprised that they are angry? To quote the perfect poem:

Harlem

By Langston Hughes

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?