Education has been awash, indeed swamped, in buzzwords for years now. Educational pundits demand rigor and accountability, backed by data-driven and test-driven instruction. Teachers work on student “grit,” helping students grapple with and fix “fixed mindsets.” They provide “bell-to-bell” instruction emphasizing mathematics, English, STEM, STEM, STEM, not to mention HST, an acronym for Health, Sciences, and Technology, not Harry S. Truman or the Hubble Space Telescope.

We are told we must provide the technological education necessary to prepare students for innovative new “jobs that don’t exist yet” — whatever the heck those are. Personally, I want to make my students “college and career ready” for jobs as suicide hotline counselors to the first Martian colonists. Within a few months of hitting the red sands of Mars, I am certain a number of our plucky astronauts will need moral support. Mars may sound great while sitting in a bar in Naples, Florida, but once the margaritas and pats on the back wear off, a sympathetic ear will be essential. Maybe I will make my students ready to open pod bay doors. If I say, “Open the pod bay doors, Hal?” how many of America’s students will know what to do? Aside from calling the administration and running to get the nurse for me, that is.

Buried in buzzwords, we get busy trying to learn to talk the talk and walk the walk. That growth mindset bulletin board? I’ve seen some beauties while subbing this year. Change your words, change your mindset, the mantra goes. I don’t disagree with that mantra.

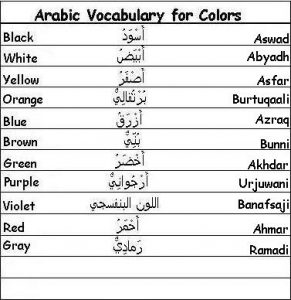

But the sheer number of buzzwords has begun to mess up my mindset and have unfortunate effects on educational effectiveness in my view. Educators’ focus can become scattered, and not all these buzzwords mesh seamlessly. Scaffolding and differentiation in particular deserve more scrutiny than they receive. Scaffolding refers to instructional supports that help facilitate learning, especially when students first encounter new subject material. We often scaffold without even thinking about scaffolding itself. Teachers intuitively understand the importance of modeling an activity before letting students loose with the scissors and glue. We display appropriate graphics, share useful related websites, KWL our way to activating prior knowledge — nonteachers, that stands for “know, want to know, learn,” not the airport code for Guilin, China or the waterworks in Leipzig, Germany. We employ other motivational techniques to get students involved. I’ve always like games myself.

At this point, I feel I should apologize to the choir. Teachers know their buzzwords, but parents and persons outside education may be hazier on our many terms and acronyms. I am about to define differentiation — and only some version of H.G. Well’s time machine would allow me to find a U.S. teacher unfamiliar with this term.

Differentiation stands for adapting instruction and materials to meet the needs of all the children in a classroom. In these times of inclusive classrooms, when the most challenged and the most gifted students may be placed in identical classes, differentiation demands care. Differentiating instruction has the potential to help special education students participate, while also allowing general education students and the gifted to meet curricular targets. Differentiate well and everybody may win. A teacher can differentiate by task, outcome or amount of support.

Educators regularly argue over exactly how to define and describe differentiation. Or they used to anyway before they started endlessly discussing testing, test prep, data requirements and the proliferation of meetings. I’d like to note that differentiation is hardly ever a slam-dunk. For example, I am not sure that any classroom exists with a range of academic levels of eight years where “everybody wins.” The only question becomes the number of losers in the room. Better teachers make sure that all students are engaged and learning. Better teachers minimize losses.

Losses occur especially in financially- and academically-challenged districts when data-driven, test-driven districts demand rigor without considering student background learning levels. Teachers can work on “grit,” and “growth mindsets” all they want, providing nonstop “bell-to-bell” instruction emphasizing mathematics, English, technology, and other STEM categories. If the material they are required to teach has been pitched too many years above their students background knowledge, teachers and students are likely to fail. I may be able to haul a student testing at a fourth-grade level up to a seventh-grade level — it’s unlikely but not impossible — but I will not manage to get a student who is testing at a second-grade level up to a seventh-grade level.

My odds of being the first suicide prevention counselor on Mars are probably about the same as my odds of closing that five-year gap. If the student was my own child and I could spend every hour of every day bonding and working with him or her, maybe we could make the leap. But I have seven hours, 180 days and 27 other students. The necessary time simply does not exist. And when “rigor” and “data” requirements force me to teach fundamentally inappropriate material, I am in far worse shape than I would be without any guidance at all.

Eduhonesty: We have so many buzzwords now that our buzzwords run into each other. I can’t give identical tests and quizzes and differentiate effectively. Yet that was the demand my administration made during my last year, even as my students failed matching multiple-choice test after matching multiple-choice test. Data-driven instruction and accountability nuked differentiation, even as I worked frantically on grit while everyone in the room kept failing around me, as they encountered material they did not understand on mandatory, undifferentiated tests they could not even read.

Ummm… STEM was in deep trouble. Those failed tests did not bode well for STEM. Rigor was killing STEM. Test-driven instruction was knee-capping grit, and not doing much for growth-mindsets. When a student always fails the tests, “mistakes help me improve” sounds suspicious and “I’m on the track” just sounds silly. The always-fail-all-the-time-track? Oh, yeah. That’s a winner for sure.

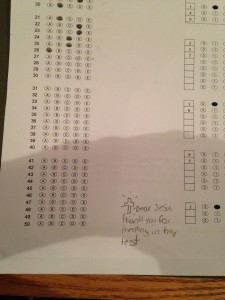

Eduhonesty: You can’t “raise the bar” without providing substantial supports to those students who are failing to jump the lower bar. Grit won’t solve that problem and rigor will likely make it worse. You can’t give and gather identical multiple choice tests designed to provide valid and reliable data while also differentiating instruction — at least, you can’t do it very often. When you insist those tests be used to determine student grades, you strangle differentiation and take regular whacks at all the mindsets of all the students who don’t know what bubbles to pick.

How about instead of trying to cram all sorts of disparate concepts together into one incoherent mishmash of an educational policy or philosophy, we simply try to teach students instead? I recommend we start by finding out what standards students do not know and teaching them whatever comes next.

Or we could continue forcing utterly mysterious ideas on students because some bureaucrat has decided all 14-year-olds must learn “X” in September. Personally, I like my idea better. When Joey finishes the fourth-grade math curriculum, why don’t we cut him a break and give him fifth grade material instead of expecting him to leap three years in a single bound?

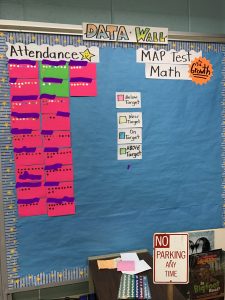

P.S. Don’t get me wrong. I favor working on growth mindsets and I am impressed by the work in the picture above. But a prerequisite for growth mindsets is a curriculum that can be accomplished without extraordinary grit or parents who can afford outside tutors.