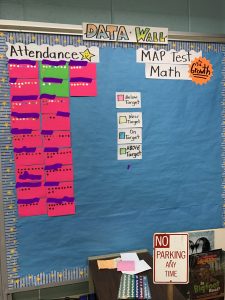

Data, data, data. Does all that data tell us more than sitting down and listening to a child read? Or more than grading weekly math quizzes? How many hours that might have gone to pedagogy have been taken away so that teachers can make more unnecessary spreadsheets, all in the name of “evidence”?

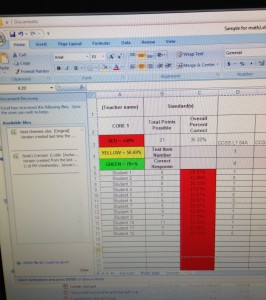

Evidence? Teachers today are told they must sacrifice hours and even days to prepare spreadsheets as evidence of the effectiveness of instruction. Evidence? The word is fraught with threatening connotations, going back through time. We watch To Kill a Mockingbird, Twelve Angry Men, Judgement at Nuremburg, The Caine Mutiny, A Few Good Men and more. Trial movies all, evidence becomes the linchpin on which verdicts will be based.

Evidence requires endless tests and quizzes, it seems, boiled down into passing categories. Grades and projects are not enough. Even that one annual test is not enough. Nothing seems to be enough.

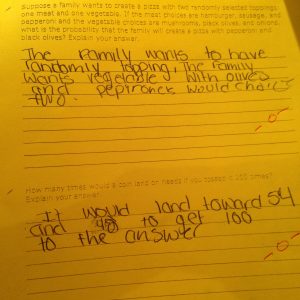

In my last year, I gave six benchmark tests, the then-two PARCC tests, regular, obligatory unit tests written by an outside consulting firm, quizzes designed to prepare students for unit tests (which hardly ever worked since the unit tests had zero to do with my students’ background knowledge), and extra tests and quizzes since my students’ grades were required to be based entirely on tests and quizzes. Other middle school teachers were giving identical tests at the same time. I had to insert extra tests and quizzes because my poor bilingual students could not even read the obligatory tests prepared by the outside consulting firm, much less do that seventh-grade Common Core math.

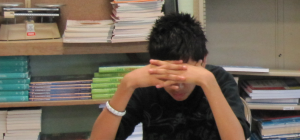

It’s surprising my students’ brains were not leaking out their ears.

In my area of Illinois, newspapers have been vigorously attacking student stress in recent articles, asking what schools can do to rein in the rising tension and anxiety besieging local students. I can think of one answer. We might stop trying to gather absurd quantities of dubious “evidence,” especially since all this testing is directly stealing from instruction. Why do we need all this evidence?

Are we under indictment? Today’s educational reformers certainly number their evidence, piece by piece. Any one who doubts this fact should spend an hour or two looking through the many boxes in the Charlotte Danielson rubric.

Are we getting ready to go to trial? If so, who will defend teachers when the “evidence” is weighted against them? Given the salaries many teachers make in poor districts, should teachers be asking for public defenders? Especially those teachers in financially- and academically-challenged districts may end up fighting for jobs, based on skewed numbers, digits twisted to create evidence of faulty instruction. Too often, educational reformers ignore the actual problems of poor reading skills, poverty, lack of English-language learning, hunger, unreliable family support, emotional and physical illness, etc. — all the many forces that complicate classroom progress.

“Evidence” has been used to push good teachers out, especially expensive, older teachers and teachers who don’t fit the latest principal’s vision of what a teacher should look or sound like. Older teachers cost more money, money they have earned through steadfast efforts put in over time. These teachers are much more likely to refuse to go along with a program when that program does not make sense to them. Given that a regrettable number of principals are all about image today, the image necessary to convince a board to renew their contract, uncompliant teachers will be eliminated if they seem “old-school” — despite the fact that the latest evidence suggests the old schools worked at least as well as the present one.

Eduhonesty: We began the major data push with No Child Left Behind in 2003 and even if NCLB has vanished, the data push remains. Yet where are the improvements our educational reformers desire? We hear all about the new reform plans such as the Common Core, PARCC and SBAC tests. We do not hear about the successes of those plans, the higher tests scores that would demonstrate increased learning. Where are the feel-good stories about widespread, increased learning in urban areas?

I guarantee readers that if those stories existed, they would be all over the internet, television and print media. Instead, our media silence should be considered deafening. Despite the data frenzy, where are the gains? Where is the improvement?

About “80 percent of freshman entering community college in the CUNY system require remediation in reading, writing, math, or some combination of those subjects,” according to the New York Times.* Recent reforms have apparently resulted in four out five community college freshman being unready to enter community college in New York.

Let’s mull that over.

If the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again – test, data, spreadsheets, test, data, spreadsheets — while expecting a different result, I would say our continued pursuit of the same old reforms could best be called batshit crazy.

The scary question: Can we go back? There’s zero “evidence” that going forward on this data-driven train will benefit our students. Yet a paradigm shift will be required to go back. We might have to put teachers back in control of their own classrooms, for example. We might have to scrap the billion-some dollar Common Core experiment. We might have to scale back on tests and data, replacing these tests with instruction and this data with lesson-preparation time.

Can we do this?

I honestly don’t know.

*CUNY to Revamp Remedial Programs, Hoping to Lift Graduation Rates, Elizabeth A. Harris, March 19, 2017

“Try different, not harder” may be the best advice I’ve encountered for dealing with ADHD. When the first shelter will not do, build again. ADHD students must understand that they will probably need to build many different shelters to survive school.

“Try different, not harder” may be the best advice I’ve encountered for dealing with ADHD. When the first shelter will not do, build again. ADHD students must understand that they will probably need to build many different shelters to survive school.