(Another post that may be especially helpful for newbies.)

My last post about PARCC testing and the failure to release PARCC results speculates that the majority of America’s students failed that test. We will know sooner or later. They may change the passing score to fix the problem.

Shifting back from big-picture to daily life, though, I feel I ought to address the problem of the test or quiz that most or all of the class fails. When I first started teaching, that problem seldom impacted my life. I was writing my own tests and quizzes based on what I had taught. Students had seen and worked with the material. They seldom failed.

You may not be writing your own tests and quizzes, though. You may be forced to teach to tests and quizzes that somebody else wrote for you. You may get those tests and quizzes a week or less before you are required to administer them. That’s what happened to me last year. The fail rate went through the roof and I was doing damage control and test retakes all year. But that’s another story. Maybe.

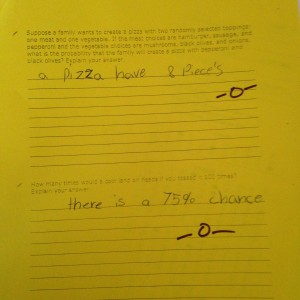

Whether you wrote the test or not, if most students failed, you can’t simply move on. Further, you have to acknowledge a truth that seemed to elude my administrators last year: You just gave a bad test. Tests or quizzes that fail everyone don’t provide much information about what students know and they discourage future efforts, especially on the part of those who studied. If you worked three hours the night before to get ready and got clobbered, will you work three hours next time? Where’s the pay-off?

For purposes of this post, I am going to assume you are writing your own tests. You wrote and gave your test. The scores came in ranging from low to abysmally bad.

Here are some tips:

You probably need to reteach. If your district has a tightly-scripted curriculum and you don’t see available time to reteach, look at the subject matter. You may be able to move on from the history of astronomy. Your students won’t suffer across the years from their lack of knowledge of Tycho Brahe. Curve the test, start on the next topic and don’t look back.

But if you were teaching two-step equations, you must reteach. Your students require this knowledge to go forward in algebra and other math classes. In a curriculum time-bind, try to find before and after school tutoring time. Reserve at least part of the class block for vital, as-yet-confusing topics like those two-step equations.

Make sure your teaching aligns to your test. Any topic you test, you should have specifically taught. No student should ever see new material on a test. That’s the problem with borrowing tests or using older tests from past years. Even if those tests prove mostly appropriate, they often contain an idea or two that the class never explored.

If you have to borrow a test in a time crunch, go through that test and eliminate problems that don’t fit well with previous instruction. In an extreme time crunch, when you can’t go through the test, allow students to drop a number of problems of their choice.

If you taught a topic but tests and quizzes show confusion, admit you don’t know how to get the idea over the plate yet. If teaching was a cookie-cutter job, they could make robots to spew out preprogrammed information. They can’t. There’s no disgrace in not knowing how best to teach a topic. We all learn by doing. The research indicates that first- and second-year teachers underperform their more experienced colleagues. Well, duhh. It takes time and effort to learn what works. Ask more experienced colleagues for help. What do they do? What works for them?

Steal lesson plans off the internet* if no one in school can help you. Use lectures on YouTube to explain a process differently when you can find quality material. Some kids listen more attentively to strangers on a screen, and a fresh take on a topic may reach learners who need extra reinforcement.

I have been known to apologize when tests went badly awry. If almost everyone failed, and I wrote the test, then I mishandled my topic or process somewhere. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with owning that failure. If I took the test from the book, but students studied the lectures, I should have warned them to study their textbook. If I assumed students knew a topic because they did a good drawing of the process, but I didn’t check beyond that to discover that most of those projects were copied off phones or home computers, I didn’t do enough pre-test assessment.

I strongly suggest test retakes be available to students. If grades fall too low, some students give up.

Allowing students to substitute projects for make-up tests can work well with many topics. Certain students learn better when they can pull out the colored pencils and markers.

As a last resort, if most or all of the class failed a test or quiz, reserve the right to throw that test out entirely, substituting a project to teach necessary concepts. Instead of testing scientific method, have your class prepare a PowerPoint or write a paper detailing the scientific method. A test that pulls down the whole class’s average benefits no one.

*Perhaps I should say borrow. If you do borrow, please give credit. When you change materials, share credit. I would write “By Sally Smith, adapted by Ms. Q” on such presentations. Giving credit for borrowed materials conveys a quiet lesson to students. We have too great a problem with plagiarism already.