http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/finding_common_ground/2015/06/do_we_practice_what_we_preach.html?cmp=SOC-EDIT-FB

“Do We Practice What We Preach?” This articles comes from Education Week, by Peter DeWitt on June 2, 2015 6:40 AM. Peter must be an early riser.

Our words matter to most of the people on the receiving end of them. Those words that come out of our mouths, especially when we are in the role of teacher, can inspire kids and adults…open them up to new learning and experiences…or close them down to the point that they shut out new learning.

How we talk says a lot about who were are. Our words can show whether we are negative, crabby, frustrated, happy or sad. Some people seem to spend a lot of time in the negative category while others approach life a bit more positive.

Why does this matter?

In a recent survey I posted about the effectiveness of teacher observations, a teacher responded, “In the charter school where I worked previously we were “Over observed” and they would find at least one thing I did wrong in each observation.

What struck me in their response was that they mentioned the school leader would find at least one thing they were doing wrong…not one thing they could improve on…or one blind spot they had in their teaching. Was this a school climate issue? Were the issues that needed improvement seen as things they did wrong? Was that how the school leader said it…or was that how the teacher felt?

The response illustrates how some observations are seen as something done to teachers, and not something they necessarily learn from after they are completed.”

I refer readers to my earlier, May 29th posts about my last observation, which occurred on the final day of instruction. My results were wholly positive, but before I got those results I fell into a state that might qualify as despair. Just the fact of the observation made me feel overwhelmed. Even if nothing had gone dramatically wrong, I picked my own efforts apart until I felt like a complete loser.

This year has had that effect on me.

In fact, I’m not sure anything had gone wrong at all. Two students had done uninspiring presentations, but one of those students had arrived late in the year and had then taken too many days off from school. The other girl did not speak English and hated speaking in public. Those two gave more or less the presentations I would have expected and benefited from having to stand up, even if they did not enjoy the process.

(Sadly I expanded this post and inexplicably lost my work. I regret the loss. I’d explained at least part of the problem clearly. I’ll try to write a synopsis of what I had.)

The question I was exploring was a simple one: What had happened to my attitude? How had I become so negative?

I am not against coaches. I liked my coach. I am not against advice. I gobble up professional development. When I looked at my total hours on the Illinois website, I laughed aloud. I’ve met my quota, that’s for sure. So what went wrong this year? Why didn’t I respond to feedback by saying, “I must get more training!” or “I must practice my nematode dissection!”

Teaching resumes often contain a trite phrase, “lifelong learner,” the equivalent of “results-oriented professional” on business resumes. I am that learner. I take classes for fun. If I have to send all my transcripts somewhere, they float in from eight different colleges and universities in three parts of the country. I’ve been thinking of finding a linguistics class to take solely because I am fascinated by language-acquisition.

Yet, by the end of the year, feedback sent me to a dark place. I expected to fail. Part of that expectation, no doubt, stemmed from my interactions with Lord Vader, my evaluator. If I ever did anything right, he was careful not to let me know. Even when I was aligned to current practices and theory, I could not seem to find a way to get credit. The fact that highflyers in my class (students sent to the dean frequently for disciplinary reasons) were working and helping other students went unnoticed. My fidget activity for a student who started the year pacing the classroom netted me a near-reprimand. Why was that boy using scissors while I was talking!? When I explained the boy’s tendency to abruptly get up and pace the classroom, I believe I got the, “No excuses!” speech. No excuses. No explanations. No hope. Here’s a version of how the scoreboard FELT:

I could not win. The “2” on that board came from my coach. In fairness, she gave me much more positive feedback than that. But a consistently negative supervisor can wipe out all the best efforts of any coaches. Lord Vader always had complaints.

My problems were simple. I needed to be doing whole-group instruction. In one class, the average grade level of my bilingual students, according to the school’s own MAP benchmark test, was third grade. These seventh-grade students had come in at a third-grade level in mathematics. They frequently were not ready for group work. They ALL needed to learn a great deal of what I was required to teach. But I was told I had to do group work. The computers saved me: I found a way to group without losing too much time.

I needed time for remedial instruction. But I was on a fixed schedule. When I said I needed to deviate from that schedule to do remedial work, I was told that my “lack of faith in my students’ abilities” was “disturbing.” (That’s where Lord Vader got his name.) My bilingual students were expected to be doing the same seventh grade work as everyone else in the grade, despite some formidable reading challenges in an age of story problems. They had to take the same weekly quizzes, regular unit tests, and standardized tests as all the other kids. I had a little input in the quizzes and none in the other tests. I was poleaxing my students on a regular basis and, if I complained, the problem was me — not the tests.

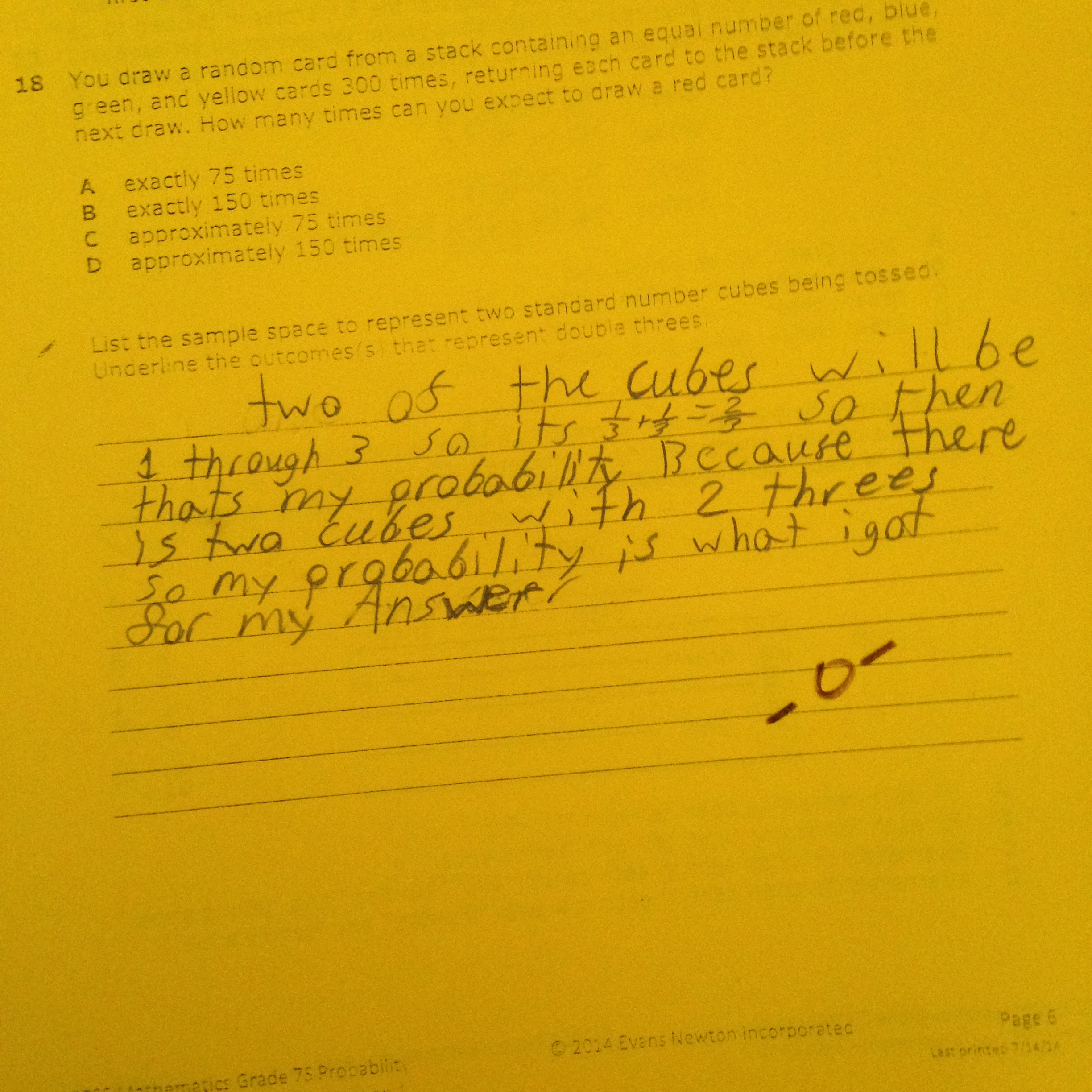

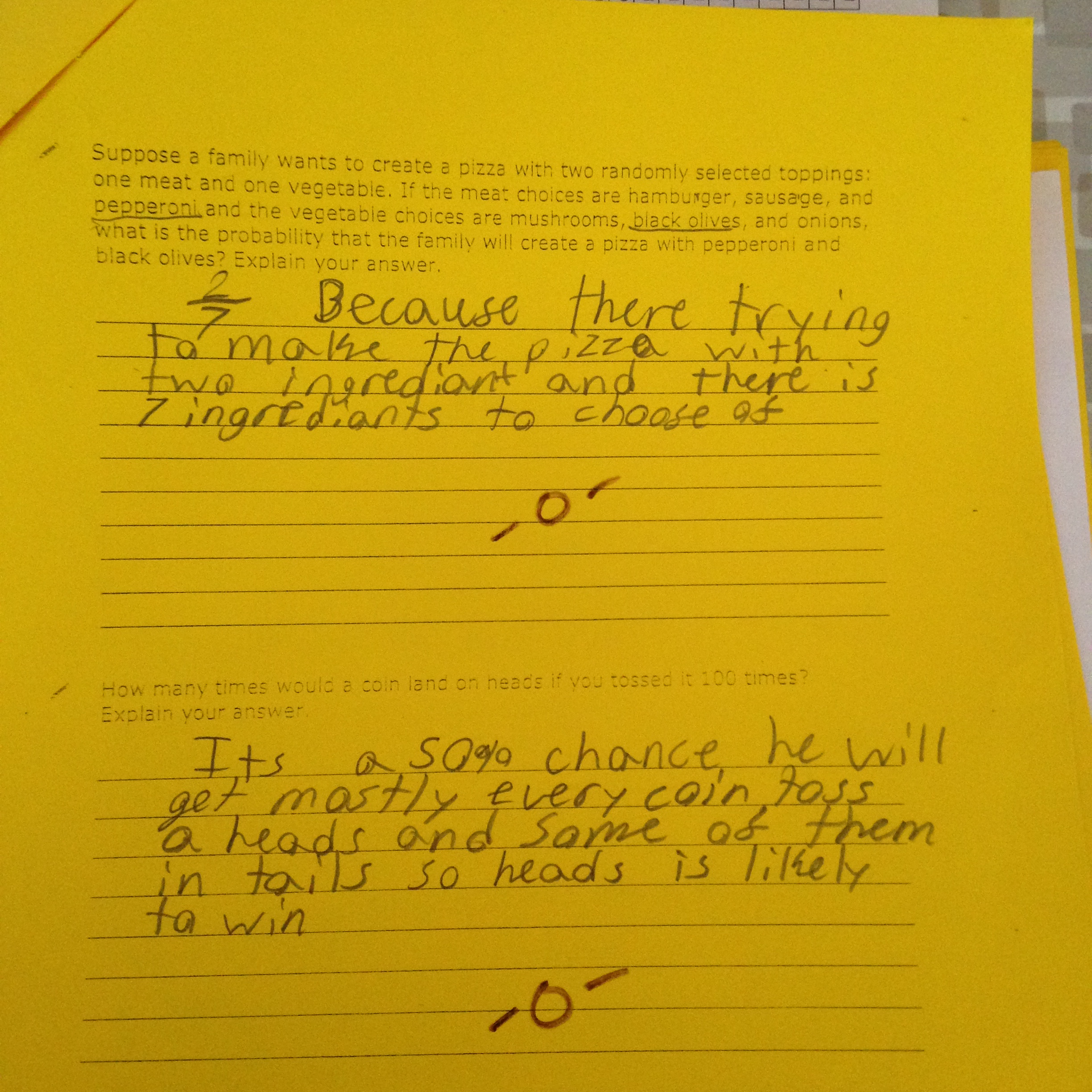

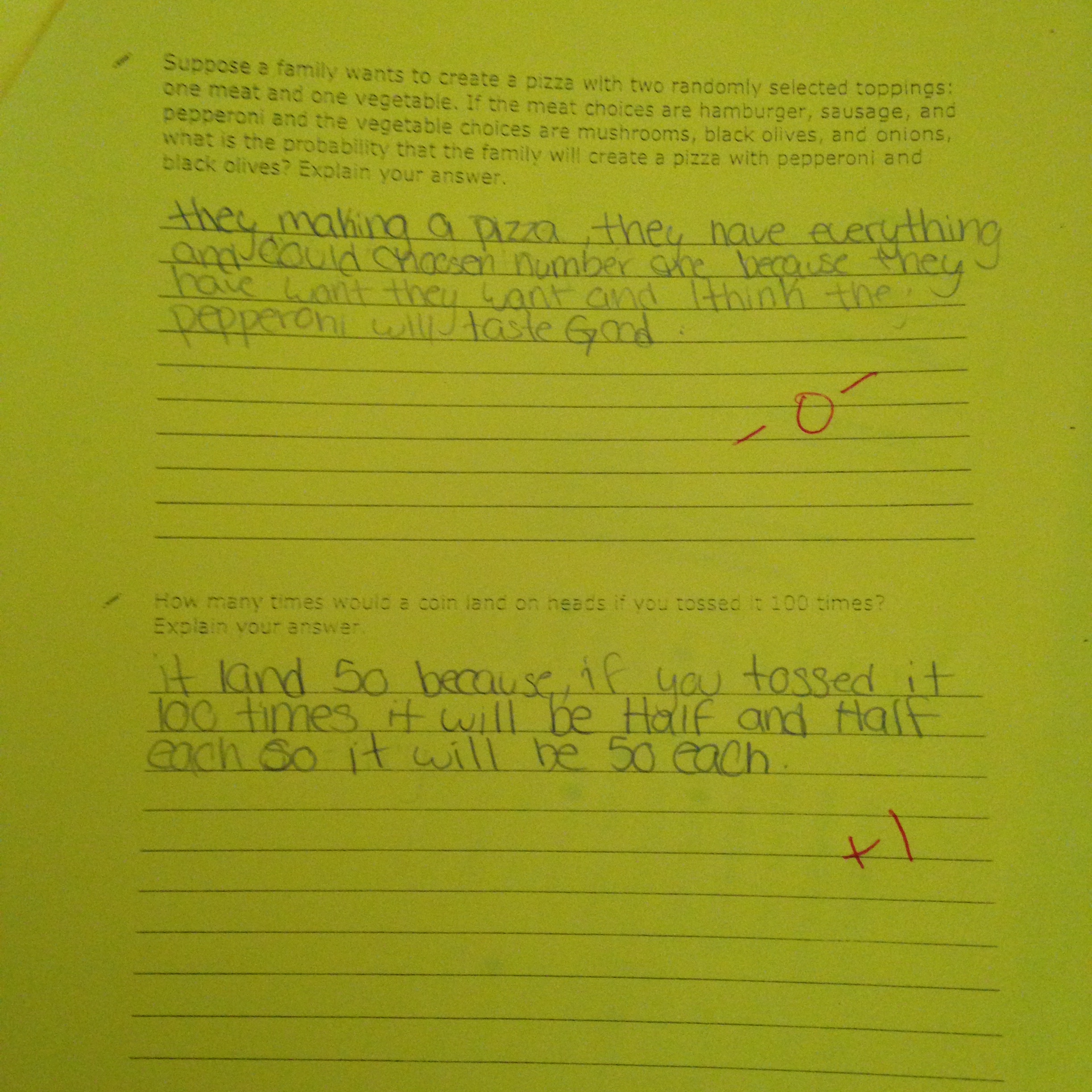

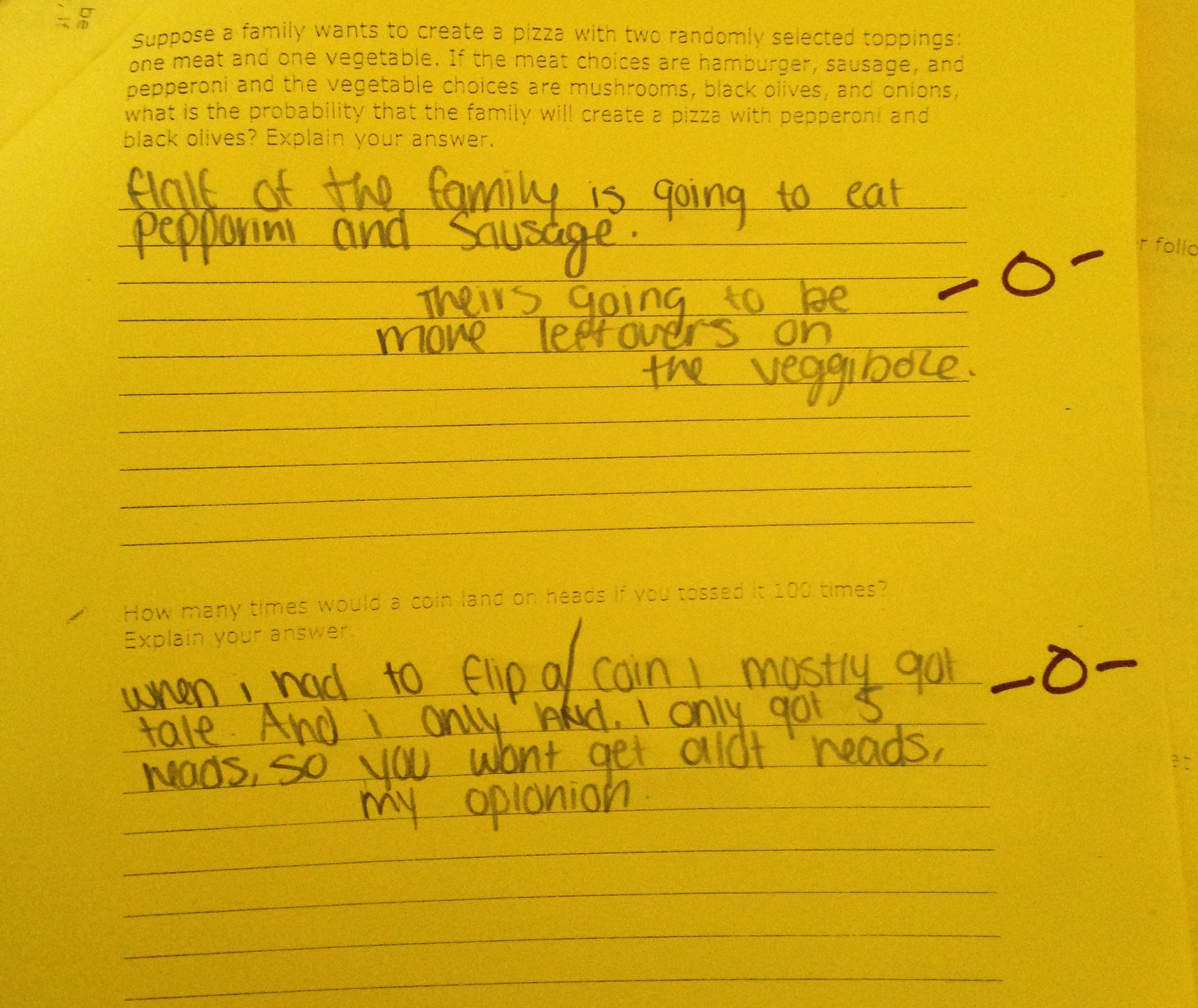

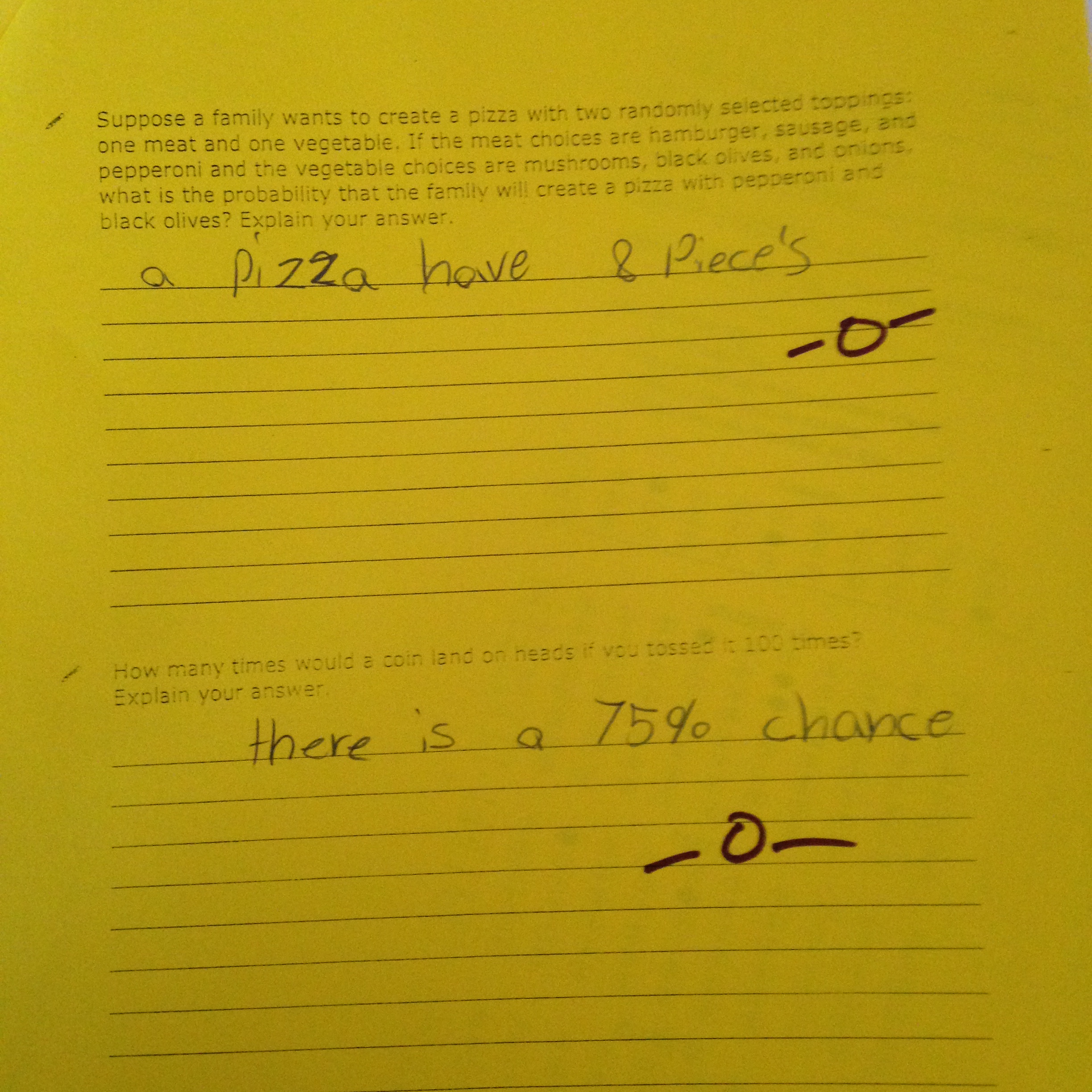

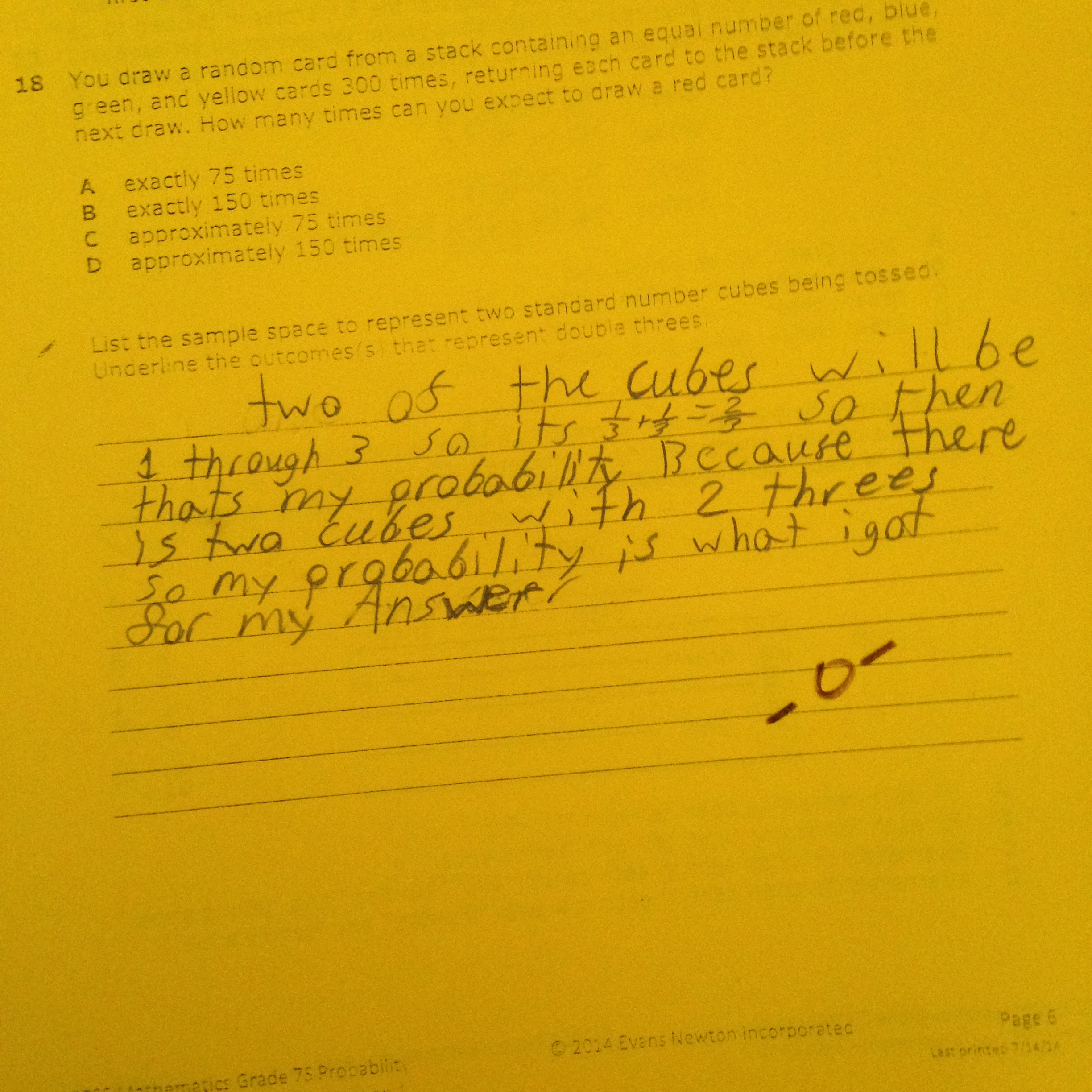

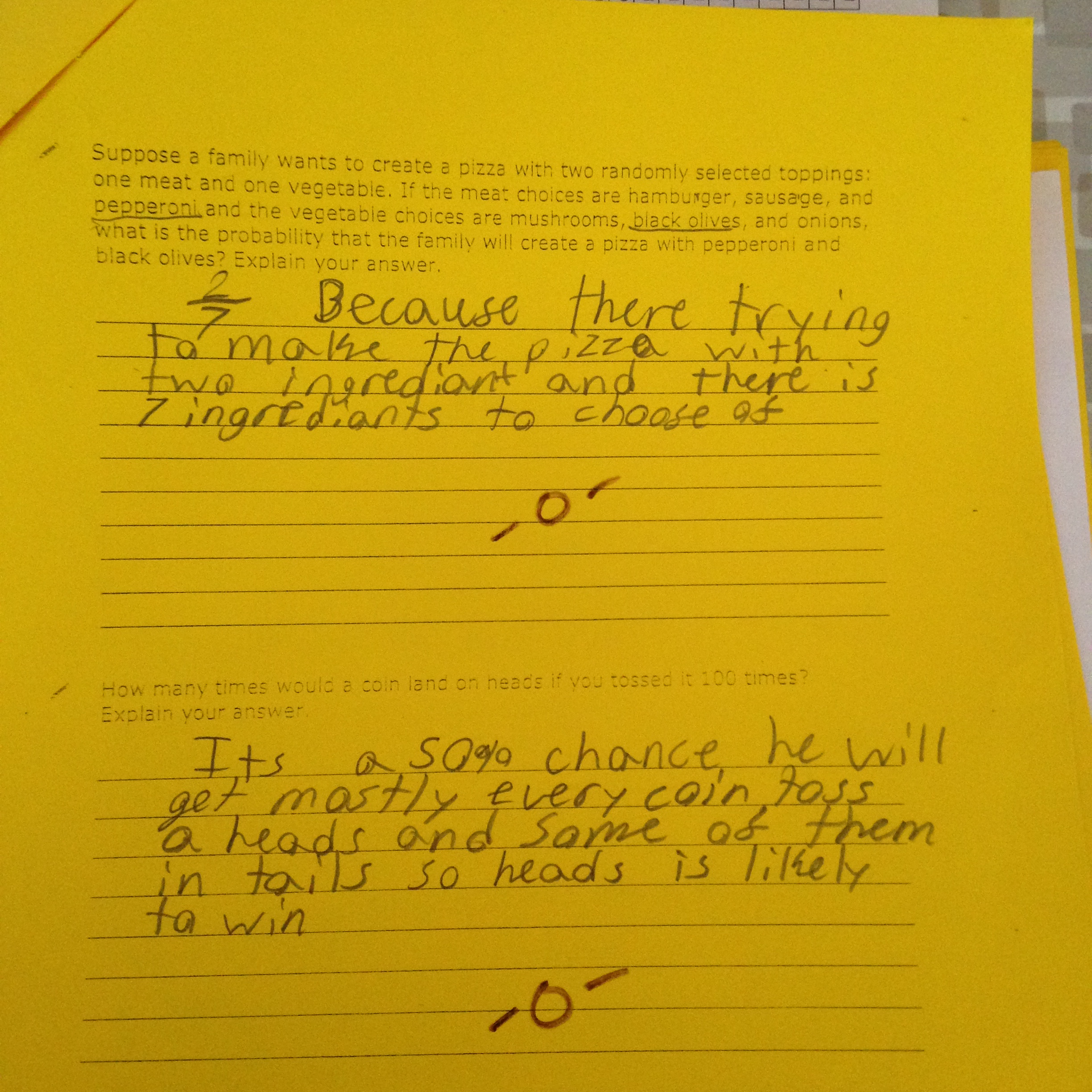

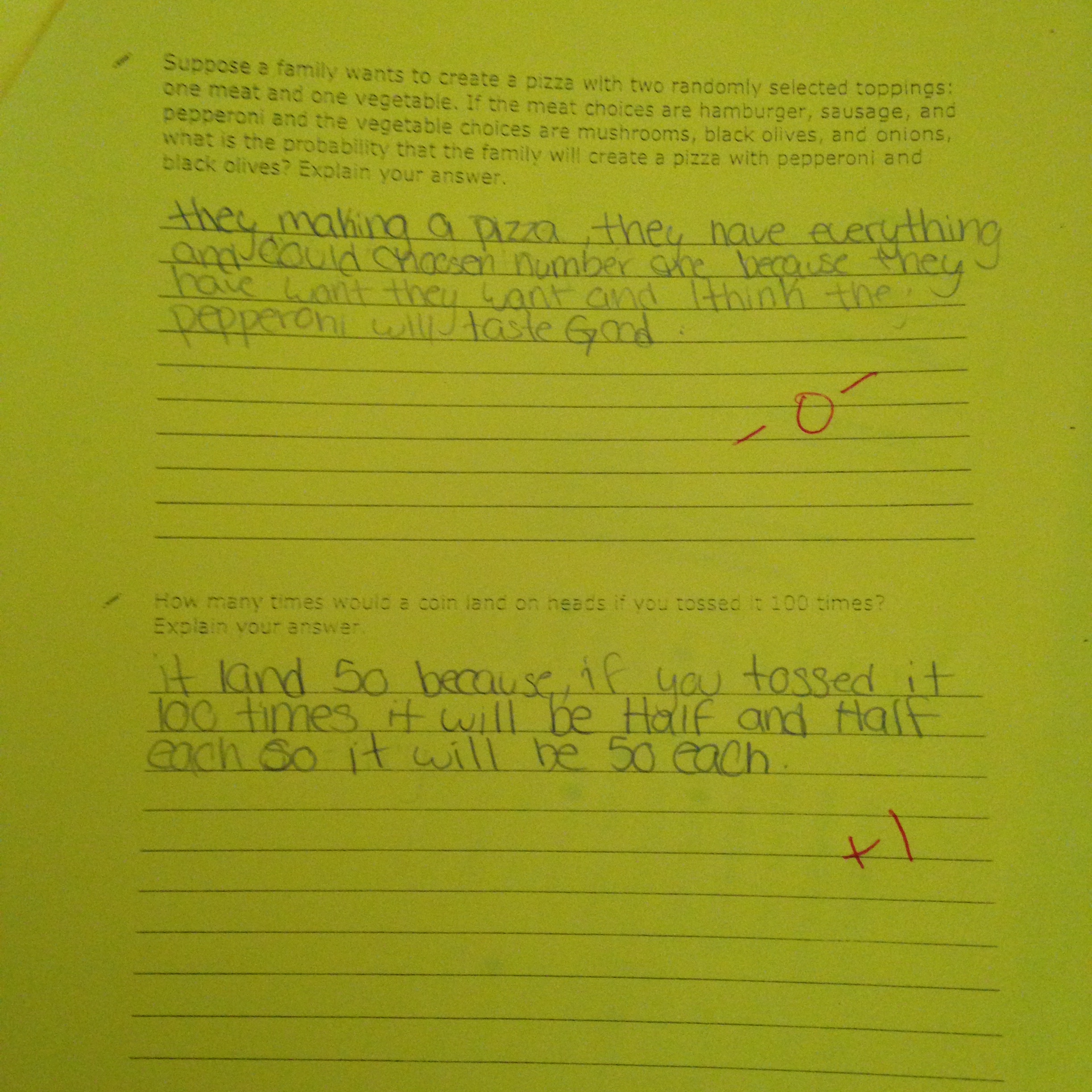

I taught furiously to upcoming tests. That’s about all I did all year; I looked at future tests and prepared instruction designed to hit the next set of required problems. Yet the tests bordered on crazy, sometimes. I encourage readers to go back into this blog to look for some pictures of those tests. Let me add a few more.

(There are six ingredients, by the way.)

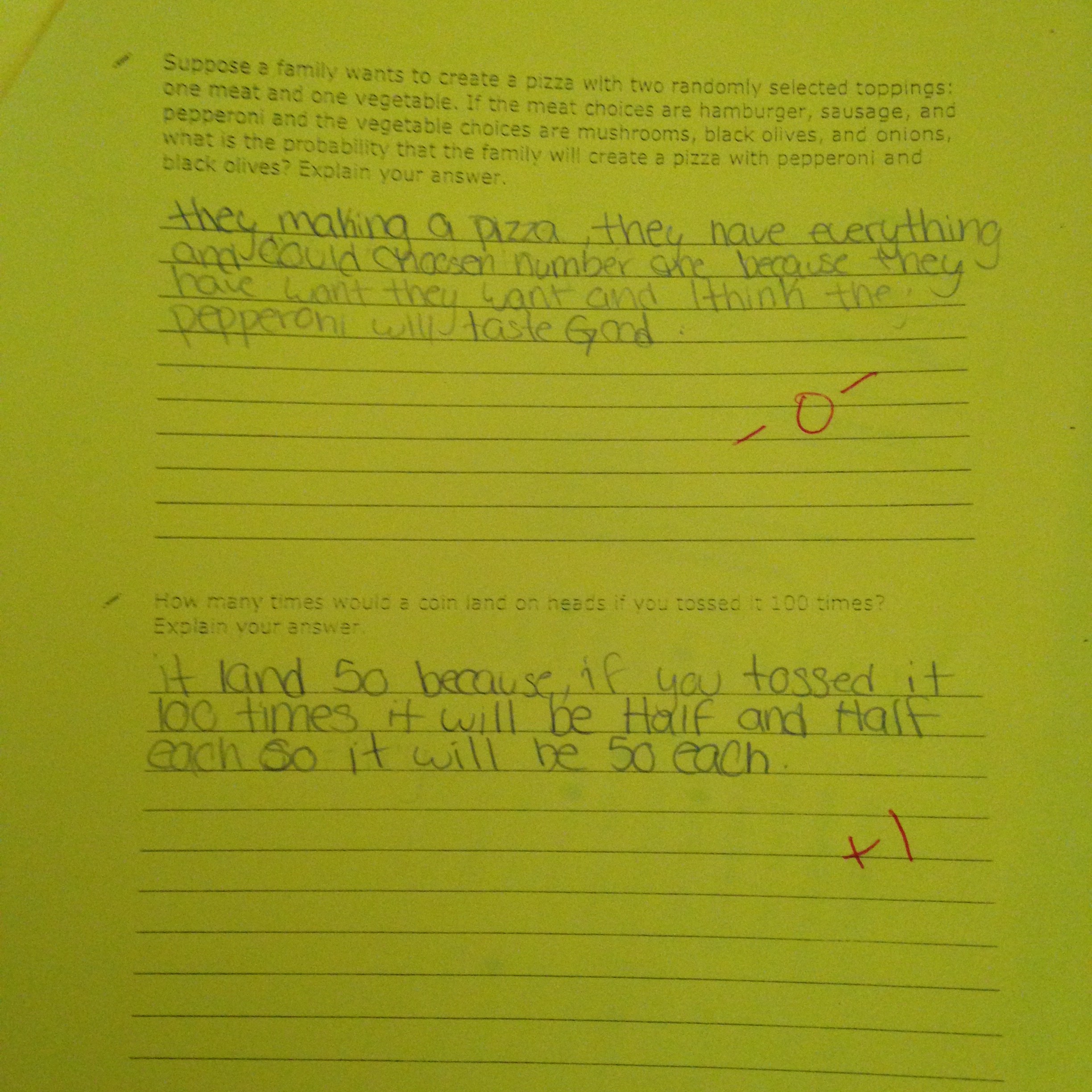

(On the plus side, students never saw the results of these unit tests. On the negative side, not a single person in my math classes got the pizza problem right. I wasn’t even able to give any partial credit.)

Why was I so negative? I could not win. My students could not do the unit tests. I could not exempt them. The quiz picture was better. Quizzes that were story-problem light might go well. I could meet with them at McDonalds to retest and attack quiz issues on Saturday. Even with quizzes, though, opportunity costs were high. I could almost never find free minutes for desperately needed remediation. We were too busy quizzing or testing.

In the meantime, I was doing my best to maintain resilience in both myself and my students but sometimes the façade was cracking. The day after PARCC testing concluded, I was obliged to give my math classes a unit test.

“Another test!?!” One student wailed. “Why?!”

“I don’t know!!” I almost shrieked back, inflection on the “I” and “know.”

That silenced the class.

“We have to do this,” I went on. I am sure I promised them music and candy for their futile efforts.

They were never able to do any of the unit tests, as the pictures above demonstrate. I never had a unit test that was a win. I gave one or two unit tests where I was able to give maybe “1” point total for a whole class in the story-problem section. These tests sucked up entire class periods, too.

Fortunately, weekly quizzes were based on actual topics under instruction and were determined by the math team as a whole, so I did have a fair number of quiz wins. Quizzes kept this year from turning into a testing bloodbath. The unit tests had been written by outsiders, though, examples of what seventh grade students ought to be able to do according to the corporation that wrote the tests. The corporation set the timetable for their administration, I believe. Those tests were a stream of spectacular fails.

What happened to me this year? Irrational, excessive testing forms part of the picture, a component of the other major problem — one of ratios. Years ago, I read a silly article in “Psychology Today” that posited happily married couples must have at least 7 good experiences for every 2 bad experiences. The male friend discussing the article with me immediately noted that more sex could fix bad ratios. We laughed about these arbitrary numbers, but the idea of that ratio stayed with me. I don’t know what the positive to negative ratio for teaching ought to be. I know that my ratio skewed too heavily toward the negative this year. Lord Vader could use some remediation, but tests made up their own rivets, tightening the chain of academic failures, due less to the lack of background knowledge in my students than to the irrationality of presenting material so far above students’ actual learning levels. Simply put, you can’t do calculus until you can do algebra, and you can’t do algebra until you understand the order of mathematical operations.

Eduhonesty: Tests should be given after material has been presented and reinforced; the opportunity for mastery must precede the exam. When I student-taught long ago, my mentor shared an idea that her teacher-father had taught her: “No one should ever see new material on a test.”

How did we lose track of that truth?

Crazy tests colored my view of this year. As my attitude sunk lower, I became less receptive to some undoubtedly good advice. As I watched my students’ faces while they struggled with these tests, I wrote off a great deal of what administration wanted to say to me. The saddest part of the tests above was the fact that students kept trying to answer questions, kept filling in blanks, when writing “IDK” would have been an honest and, I believe, better use of their time.

P.S. The special education teacher had the same problems I did. She complained to me. I provided moral support. She also retired at the end of this year. We both agreed. We love the kids. We love teaching. Whatever we were doing this year, though, that’s not teaching, and we don’t want to do it anymore.